Richmond Stories

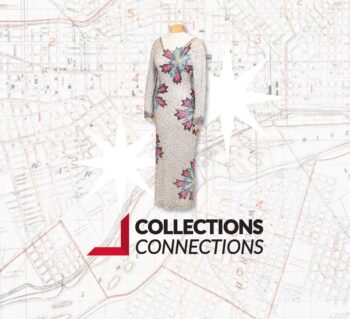

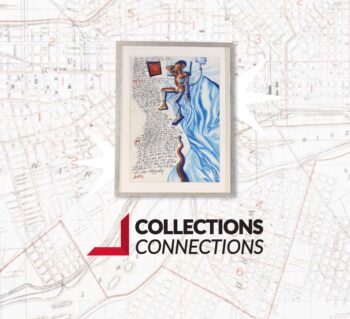

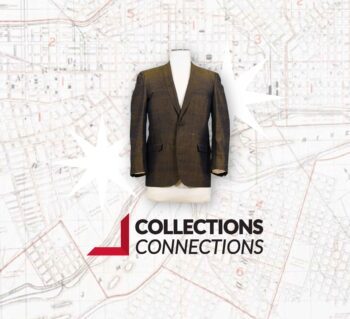

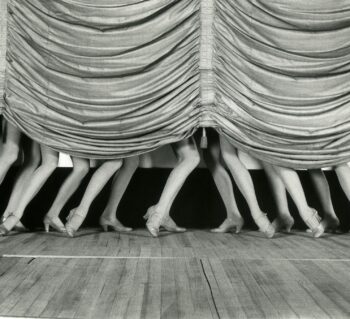

Discover Richmond Stories through educational resources from the Valentine's unique collection of objects, textiles and archival materials that document our region’s complex history.

Featured Stories

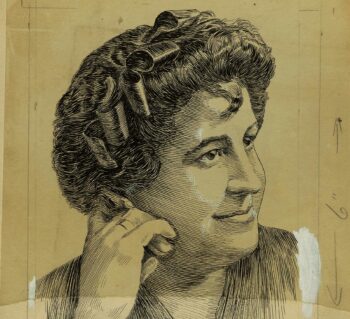

Maggie L. Walker: Richmond History Maker

Maggie L. Walker – a mother, a leader, a civil rights activist, an entrepreneur, a Richmonder.

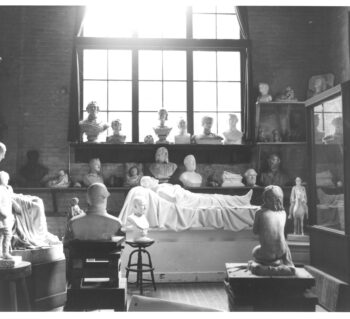

Edward Valentine's Sculpture Studio

A Quick Look: For thirty-nine years, Edward V. Valentine created some of his most well-known sculptures in the carriage house turned studio at 809 East Leigh Street in Richmond.

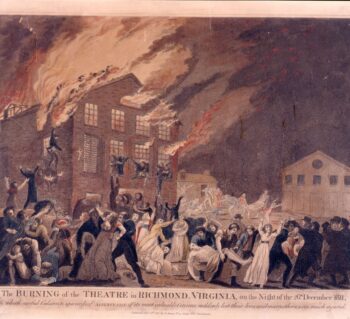

1811 Richmond Theater Fire

Richmond Theater Fire in 1811 that killed 72 people including the governor of Virginia.

Richmond Timeline

Explore Richmond history using our interactive timeline that features events and stories using objects, documents and images from the Valentine’s collection.

Videos

Explore Our Collection

Discover online exhibitions and start your collections research here.

Collection Database Search

Explore the Valentine’s online collection database. Our digitized collection is actively growing! Please check back regularly to see new additions.

Sculpting History at the Valentine Studio

Explore online resources related to the Valentine’s upcoming exhibition, Sculpting History at the Valentine Studio: Art, Power and the “Lost Cause” American Myth.

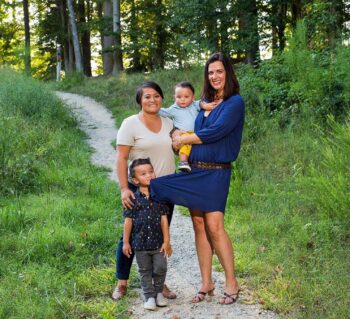

Richmond Stories Podcast

Presented by the Valentine, the only museum dedicated to sharing Richmond’s challenging history, Richmond Stories uses conversations with change-makers, advocates, leaders and residents to explore the past, present and future of this (very) complicated place we call home.