Bingo!

For much of the 20th century, Virginia has had some of the strictest anti-gambling laws in the country.

By Valentine Museum Staff

A long tradition of horse racing and dice and card-playing among the state’s illustrious white citizens had destroyed the wealth of a number of colonial families, including that of William Byrd III, son of our city’s founder. A notorious gambler, Byrd sold off his vast estate in 1767 and still could not cover his gambling debts, which he had racked up by the age of 30.

By the 1890s, gambling was deemed so detrimental to all classes of society that the General Assembly could no longer countenance it, no matter how traditional. They banned race track betting in 1894, then tightened the law just a year later. Over the next several decades, with support from Protestant churches, our state government essentially banned all forms of gambling. It was not until 1973 that our legislators decided to loosen restrictions. They did so narrowly, allowing only certified non-profits to host Bingo games. The logic behind the new law was that if Virginians were going to gamble, the profits could at least go to good causes.

Bingo was hugely popular in the United States in the 1930’s, during the Great Depression. Movie houses and fairs held jackpot games, while families began to play non-gambling versions of the game at home. The basic premise gave each player a large card, gridded with numbers. A non-player then drew numbers randomly from a hat, or even a fancy lotto ball machine. If that number appeared on a player’s card, they covered that number with a chip. A player won—calling Bingo!—when they achieved a row of five straight chips. Other versions of the game also rewarded other configurations, like chipping all four corners. The appeal of the game was its simplicity. It could be played by all ages, in very large crowds. The crowd-friendly game also created big jackpots for little pay-in.

According to the 1973 law, only federally recognized non-profits could run a game, with volunteers who were members of the non-profit. The price of cards and jackpot amounts were capped, as well as player age and profit percentages. Soon, churches, synagogues, civic organizations, and athletic clubs had set up tables in their basements and multi-purpose rooms to host Bingo. The public came in droves. The average Bingo player in 1975 lost $10 per night. Smaller games presented a larger chance of winning smaller jackpots, but a large game could pay out as much as $1500.

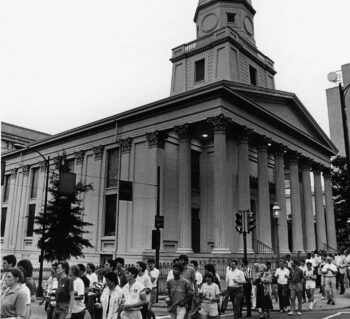

By 1977, Richmonders were spending over $1 million a year on Bingo. The game had grown so huge that the original law, which charged local governments with enforcement, failed to address a large number of problems. City and county governments scrambled to regulate Bingo. Richmond City Council unanimously passed a 6% admission tax—the same charged at movie theaters—in order to fund regulation in the city. Charities were required to file annual reports of their profits and payouts with auditors. Then a special commission was appointed to investigate complaints and enforce building, fire, and safety codes at the packed Bingo halls.

The metro Richmond area saw 150 organized Bingo games every week in 1978. That year, non-profits raised around $6 million with Bingo proceeds alone. The largest Bingo game in town was the annual Cystic Fibrosis fundraiser, which filled the Richmond Arena with 1700 players, who raised $32,000 for the cause. In fact, Bingo had grown so huge in the Richmond area in just five years that these non-profits did not have space for the growing crowds of players. The groups tried to buy new buildings or build larger annexes. But the law stipulated that Bingo proceeds could only be used for charitable expenses. Virginia’s attorney general was forced to clarify that non-profits could not buy real estate with their Bingo profits. So, the groups began to rent space for their Bingo games.

For-rent Bingo halls began to pop up all over Richmond. Places like “Crazy Jack’s” on Parham Road provided space and all the (sometimes expensive) equipment for a large Bingo game. But with expansion into the rental market came abuses. Some groups paid more in rent than in charitable activities. In 1979, the General Assembly passed more laws regulating Bingo, requiring fair-market rents and limiting buildings to 2 games a week. The rental halls were prohibited from keeping a percentage of Bingo profits.

By the early 1980s, Temple Beth-El, the Fraternal Order of Police Lodge, the Civitan Club, St. Paul’s School, the Christian Workers Council, the Tuckahoe Moose, the Ginter Park Junior Women’s Club, the Metropolitan Junior Baseball League, the Richmond Speleological Society, the Jewish Community Center, and St. Mary’s Catholic Church all hosted Bingo games. Across the state, civic clubs, animal shelters, fire department, little leagues, and school districts all used on Bingo profits to keep their organizations running. Generally, for $2 a player received three cards at a Bingo game. They could also buy Instant Bingo cards, much like scratch tickets, for 25 cents each. The low stakes made the game seem less like gambling and more like fundraising—until players began to buy and play 30 cards at once!

Proponents of non-profit gaming argued that it was much more lucrative than selling candy and magazines door to door, or outright begging for funds. Fire stations and schools could raise money for new equipment without draining tax coffers. And, unlike casino gambling, someone in the crowd always wins at Bingo. Despite the long odds of winning, this is true. Richmond non-profits only profited 25-40% in any given game, with the majority of cash going to the jackpot, and the winner. Also, unlike casino gambling, there’s no way for the house to cheat. Everyone watches the caller pull the numbers. Of course, that does not mean that the players did not cheat. They certainly did, by removing numbers from their cards or stamping them over with new numbers.

Like more traditional gambling, Richmonders played Bingo for many reasons. Some treated it like simple entertainment or charitable giving, while others played for income. Elderly people played to get out of the house and socialize. Others, inevitably, played because they’d become addicted. The slightest hiccup in a game could bring out the worst in a Bingo crowd. A snowstorm cancellation or a botched call often led to unruly confrontations. Security guards patrolled many Bingo halls to keep the peace. In 1976, three years after non-profit Bingo became the first legal form of gambling in the state, Gamblers Anonymous sought to open a chapter in Richmond—the first in the state.

Non-profit Bingo is still big in Richmond, though it is waning now that Virginia allows two other forms of gambling. The Virginia State Lottery was sanctioned in 1988. Horse track betting became legal in 1989. For some, charitable Bingo has seemed like a near-perfect solution to fundraising. But as profits exploded, charities spent a lot of those profits on expanding their Bingo operations. Local and state lawmakers tried to find a balance. In 1994, Henrico County banned Instant Bingo cards. But state caps on winnings were eventually raised, as well as the cap on the number of games allowed per week. The flow of more money inevitably attracted criminal activity. In Henrico County, a man nicknamed “The Bingo King” skimmed $700,000 from local charities in the 1990s. In 1996, due to rampant abuse like this, the state appointed a commission to regulate Bingo.

The percentage of profits required to be spent on charitable activities was also lowered to just 10%. But into the 21st century, many charities struggled still to meet those requirements.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | Bingo! |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | December 2, 2021 |

| Updated | May 24, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |