Essay: Edward Valentine’s Life and Career

An in-depth look at Edward Valentine's artistic and museum pursuits.

By Kate Sunderlin

Ph.D., Co-Curator of Sculpting History: Art, Power, and the “Lost Cause” American Myth

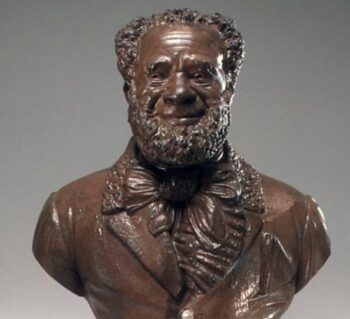

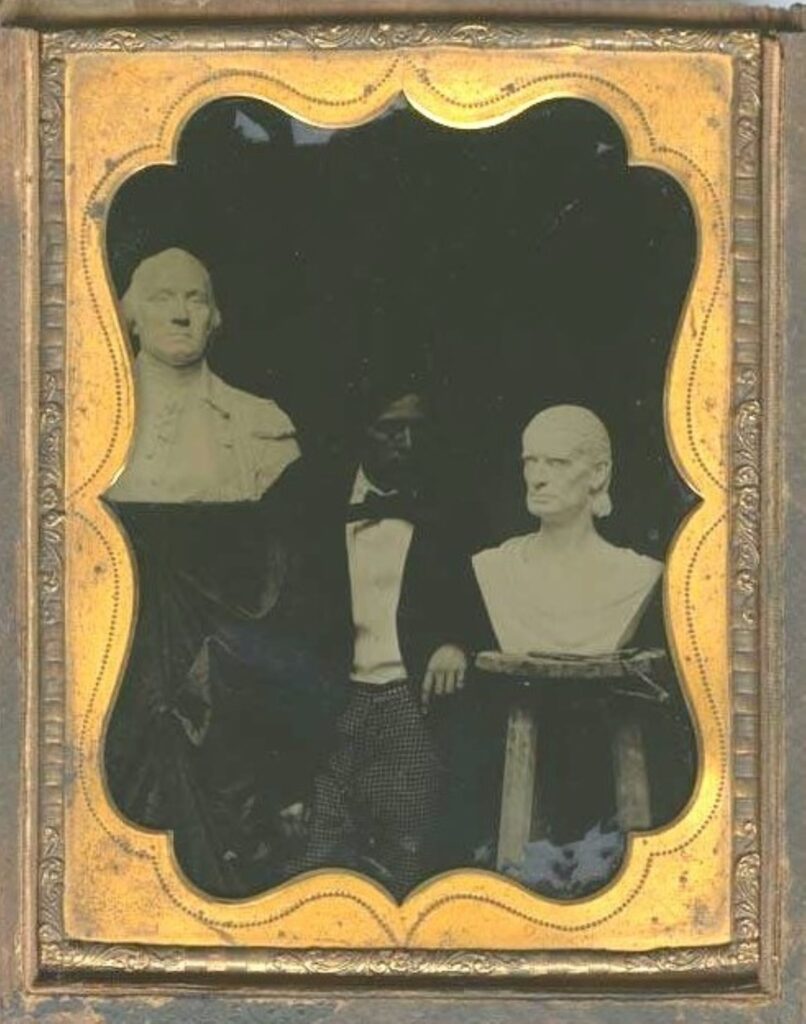

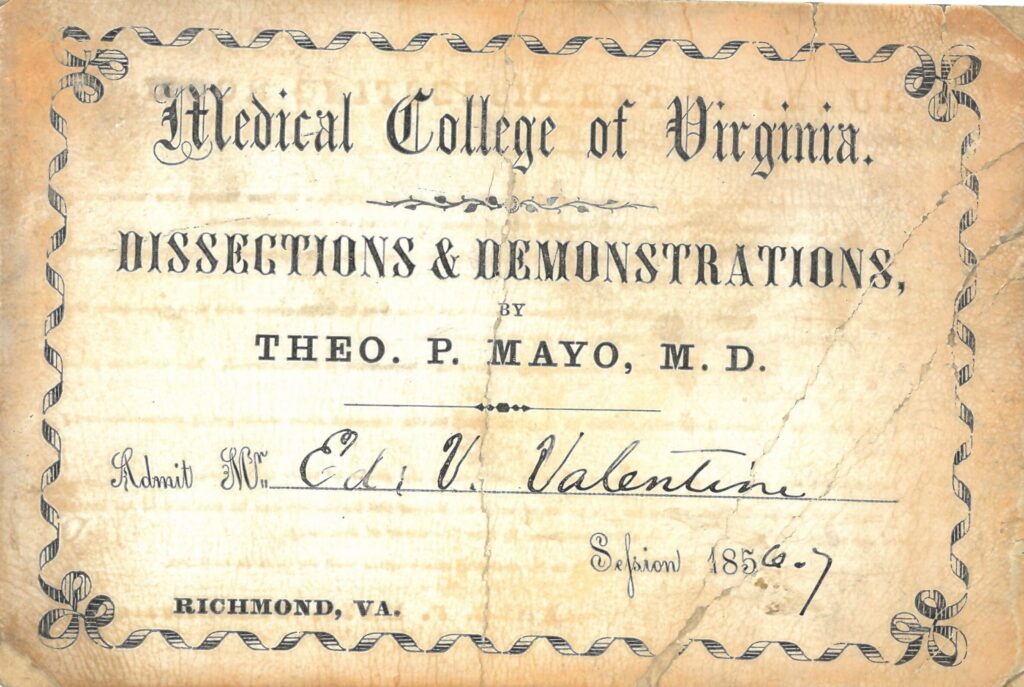

Edward Virginius Valentine was born in Richmond, Virginia on November 12, 1838 to Mann Satterwhite Valentine (1786-1865) and Elizabeth Mosby Valentine (1801-1872), their ninth and last child. Mann Satterwhite Valentine was a wealthy merchant who owned enslaved workers. Like most middle and upper class children, Edward was educated at a private school within Richmond, the Richmond Academy, administered by Dr. Socrates Maupin, later a professor at the University of Virginia. Valentine studied modeling and drawing informally under William James Hubard, a British painter and sculptor close to the Valentine family, Dr. Arthur Peticolas, and Oswald Heinrich, a mining engineer. To further his artistic training, Valentine enrolled at the Medical College of Virginia and attended courses on anatomy from 1856 to 1858. During this period, Valentine devoted himself completely to anatomical studies, drawing and making anatomical studies from plaster casts after anatomical body parts.

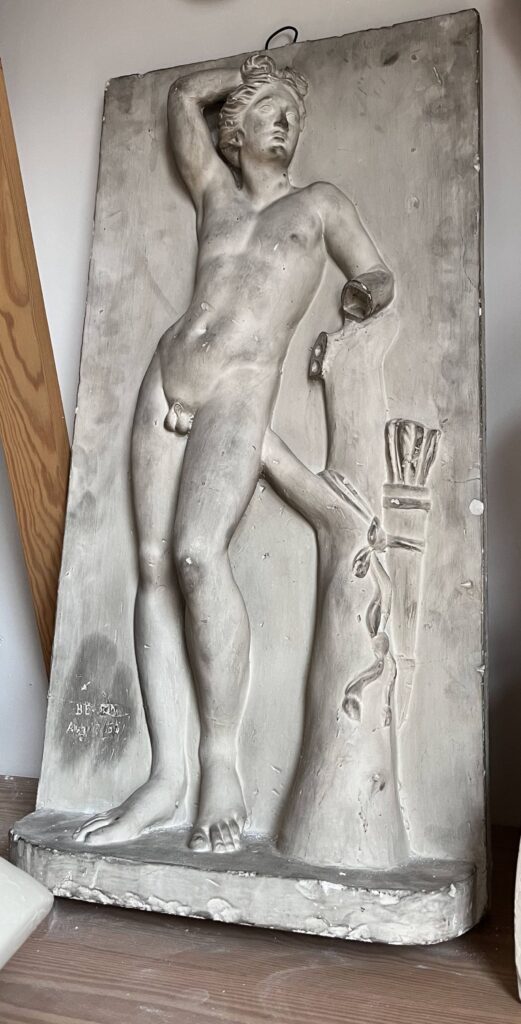

Like many American sculptors, Valentine studied abroad. He left Richmond for Europe on September 28, 1859, when he was only twenty years old. He spent some time in the studios of the painter Thomas Couture (1815-1879) and sculptor François Jouffroy (1806-1882) before traveling to Berlin to study with sculptor August Kiss (1801-1865). While in Kiss’ studio, Valentine made copies of famous art works, like his Apollino, and portraits of friends and acquaintances of Kiss and his wife. He also sculpted a statuette of Robert E. Lee in May of 1864 that was cast in October of 1865 and later sold at the Southern Bazaar in Liverpool, England to benefit the Confederate war effort. This statuette has never been found. The death of Kiss and Valentine’s own father in 1865, as well as the end of the Civil War, prompted Valentine to return to the United States.

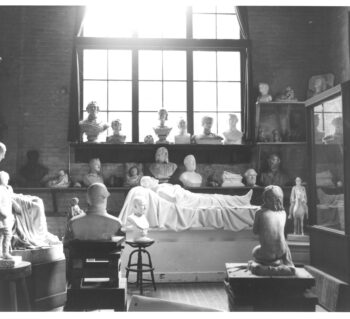

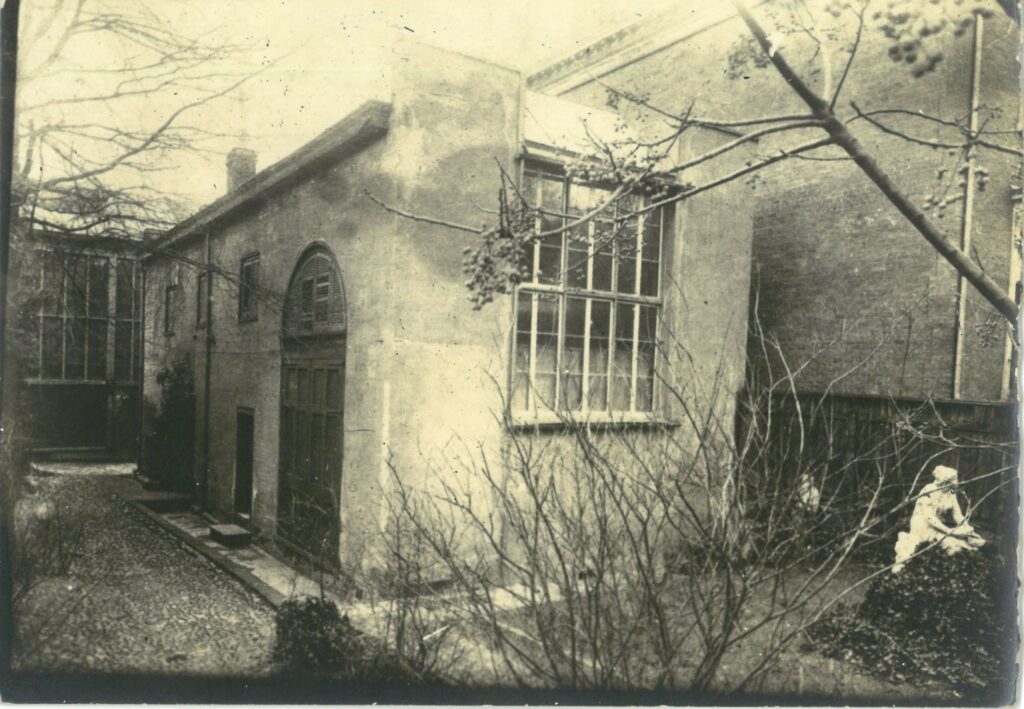

After his return, Valentine opened his first studio at his family home on Ninth and Capitol Streets. Between 1865 and 1871, he moved several times, including to a rented studio above his brother Mann S. Valentine II’s dry goods store at 1208 East Main Street. One of the first busts Valentine completed after returning to Richmond was a bust of Thomas J. (Stonewall) Jackson. He would sculpt many more Confederate politicians and generals over his career including Jefferson Davis, William Smith, Christopher Memminger, John Breckinridge, J.E.B. Stuart, George Pickett, Mathew Fontaine Maury, P.G.T. Beauregard, and Robert E. Lee. In August of 1871, Valentine bought a 1830s carriage house at 809 East Leigh Street, originally part of the Hayes-McCance property that he remodeled into a studio. The existing structure measured twenty-two by fifty-six feet and served as both his working studio and, briefly, his living quarters.

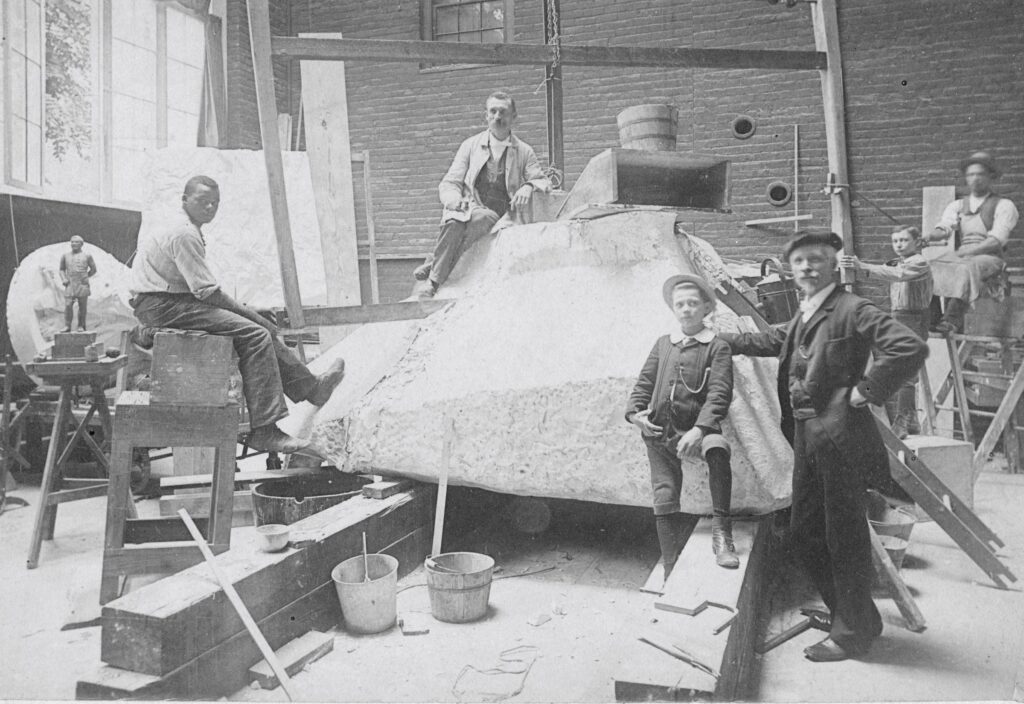

It was here that Valentine made the majority of his works, including the Recumbent Lee for the chapel at Washington College (now Washington and Lee University), the classical sculpture Andromache and Astyanax based on the epic poem the Illiad and displayed at the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1893, and the statue of Jefferson Davis for the Davis Monument on Monument Avenue in Richmond, VA (torn down by protestors in 2020).

By the late 1880s, Valentine’s reputation had grown so that he had an increasing number of larger commissions necessitating an expansion to his studio. He broke ground in September 1889 for a larger building, known as the Annex, behind his Leigh Street studio that he used for casting and marble-cutting. According to newspaper accounts, it was to be the largest in the country. Once the Annex was complete, Valentine used his older studio as a modeling studio where he could receive guests and clients and display smaller works. Some of his more famous guests included future U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, then president of Princeton University, and British author Oscar Wilde.

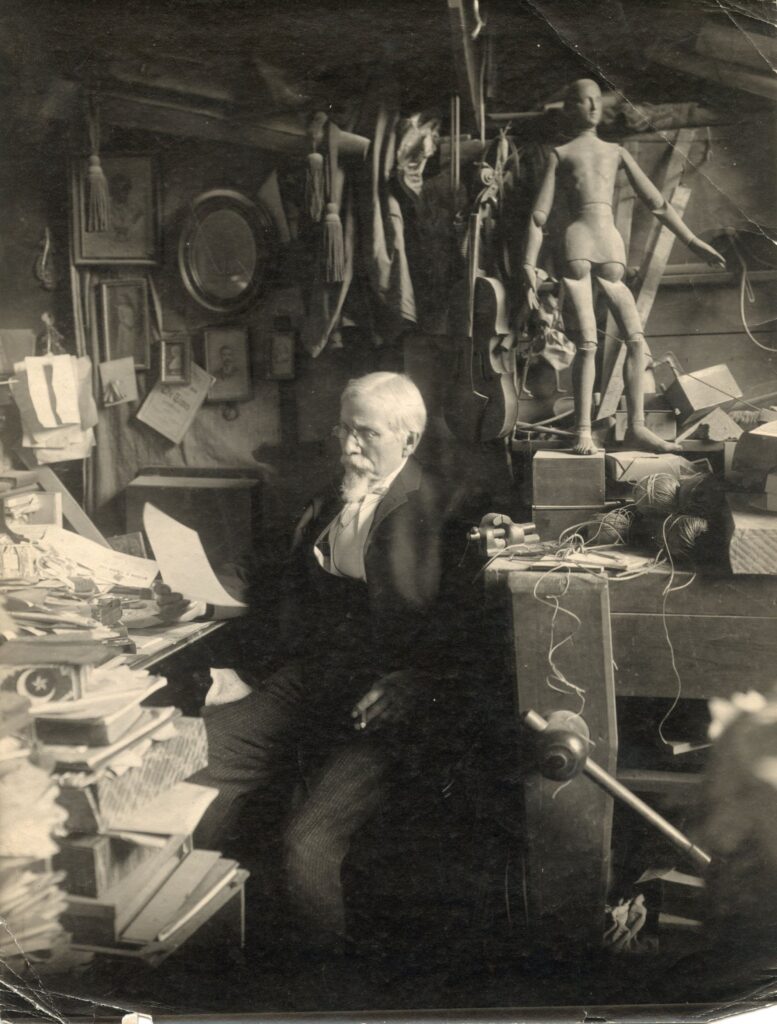

Valentine retired around 1910 and gave up the use of his studio on Leigh Street, where he had created the majority of his works, moving to an apartment overlooking Monroe Park on West Franklin Street. At a table filled with casts, compass, T-squares, plumb lines, pencils, and other tools of the trade, Valentine would hold a daily drawing class in a room of his apartment dedicated as his studio. While his students worked, Valentine would sit in a rocking chair in his bedroom and work on his memoirs. Valentine was an active member of several institutions and organizations during his lifetime and retirement, including (but not limited to) the Virginia Historical Society (appointed to the Executive Committee on December 28, 1880 and President on October 26, 1922), the Confederate Museum (appointed to the Advisory Board on December 2, 1896), and the State Art Commission (joined November 14, 1916). He also served as the president of the Valentine Museum, founded by his brother Mann S. Valentine II, from its incorporation in 1894 to his death in 1930.

Valentine was married twice. He first married Alice Church Robinson on November 12, 1872 at a ceremony in Baltimore, MD. The couple lived in a number of different homes around Richmond while Valentine retained his studio on East Leigh Street. Alice Valentine passed away after a brief illness in August 1883. In January 1892, Valentine married again, this time to Kate Coles Friend, widow of William Mayo. Kate Valentine passed away in 1927. Neither marriage resulted in children. All three are buried in the Valentine family plot in Hollywood Cemetery.

Sources

- Valentine owned 15 enslaved workers in the 1840 Federal Census, 10 in 1850, and 7 in 1860, plus purchase records in MSVI Papers at the Valentine.

- Elizabeth Gray Valentine, Dawn to Twilight (Richmond, VA: William Byrd Press, Inc., 1929).

- Perhaps not coincidentally, Hubard had also made copies of Houdon’s George Washington, though in bronze. Margaret J. Preston, “Edward Virginius Valentine,” American Art Review Vol. 1, No. 7 (May 1880): 277-282.

- Hill’s Richmond City Directory, 1869 and 1870

- Richmond City Deed Book 94B, 496; Mann S. Valentine II acquired the Hayes-McCance House in 1888 and it was demolished in 1893.

- Mary Wingfield Scott, Houses of Old Richmond (New York: Bonanza Books, 1941),138-141.

- Edward V. Valentine Papers, Valentine Museum Archives, Richmond, VA.

- Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, VA), September 21, 1889.

- The State (Richmond, VA), November 13, 1889.

- Gilberta S. Whittle, “Valentine’s Work with the Chisel,” Baltimore American (Baltimore, MD), October 12, 1902.

- History of the Virginia Historical Society. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 39, No. 4 (Oct., 1931), 329.

- The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Jan., 1923), x.

- Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 15, 1916, 10.

- Virginia Herald, November 14, 1872, 2

- Barbara Batson, Ned’s Sheds, unpublished manuscript, 2001, Valentine Museum

- Daily Dispatch, August 25, 1883, 1.

- Norfolk Landmark, January 7, 1892, 2.

- www.findagrave.com.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Kate Sunderlin, Ph.D., Co-Curator of Sculpting History: Art, Power, and the “Lost Cause” American Myth |

|---|---|

| Work Title | Essay: Edward Valentine’s Life and Career |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | November 2, 2023 |

| Updated | May 24, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |