First African Baptist

In the antebellum era, the Baptist church was popular in southern African American communities in part because it conferred more rights to Black members than other denominations. Often, Baptist churches offered free and enslaved Blacks full membership, and sometimes even administrative roles. This may be difficult to imagine now, but many Baptists churches at that time were not only integrated, but claimed many more Black members than white. In Richmond, this was indeed the case.

By Valentine Museum Staff

By 1840, 400 white Baptists worshipped regularly with 2,000 Black Baptists. Membership, however, did not mean equality. Black congregants could not hold leadership roles and were consigned to segregated seating. This double imbalance—with greater numbers and lesser rights—emboldened Richmond’s Black community to finally demand a church of their own—an unprecedented undertaking that would lead to more unprecedented demands for autonomy, justice, self-governance, freedom and, eventually, the full rights of citizenship.

But in 1840, when Black members of First Baptist Church asked their white deacons for permission to form their own congregation, the simple idea of Black assembly seemed far off. Nine years before, in 1831, Nat Turner’s rebellion had made white Virginians terrified of Blacks convening at all. And since Turner had been a preacher, the act of unsupervised Black worship had been deemed even more of a threat. For this, the General Assembly had specifically banned independent Black worship and Black preachers, a law enforced with whipping. These restrictions were still in affect when the deacons of First Baptist Church agreed to the radical proposition.

To accommodate state law, the establishment of an all-Black church in Richmond had qualifications. First and foremost, the new church had to be led by a white preacher, appointed by an all-white Baptist board of male overseers. Secondly, the church’s constitution and any changes to the document had to be approved by that body. Services could only be held during daylight hours.

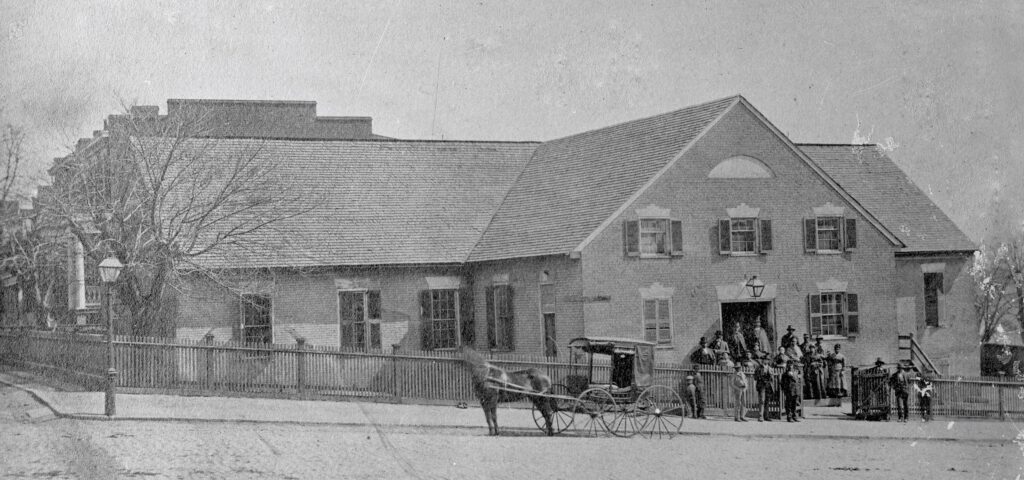

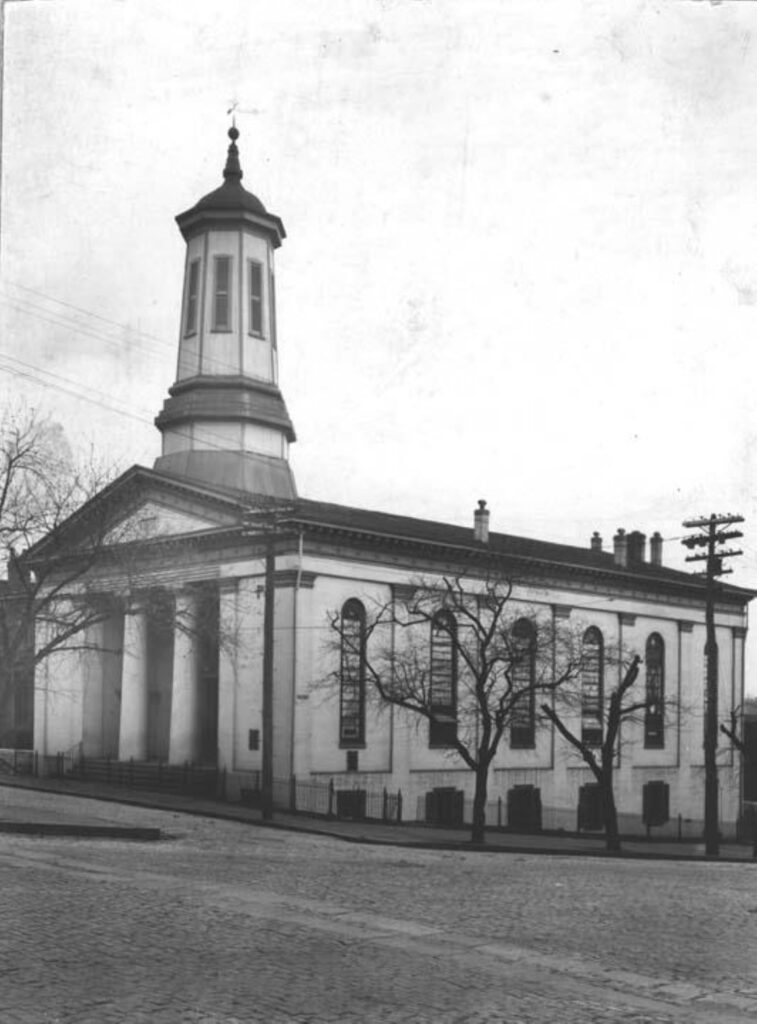

Within a year, First African Baptist Church raised $7,500 to buy the brick building that had housed their parent church, First Baptist. Though white members gave generously to the fund, Black members, including many who were enslaved, contributed more than half the amount. The building on College Street at Broad was theirs. And within it, 940 members who held virtually no power in the city could aggregate their skills and passions into a powerful institution that served the needs of Richmond’s Black community. The potential became clear very soon, as their appointed white pastor, Robert Ryland, granted Black members a lot of leeway in managing their own institution.

Ryland was no abolitionist. In fact, he routinely preached about the submission of servants to masters. One enslaved congregant, Henry “Box” Brown, who would mail himself to freedom in a wooden box, later recalled that Ryland relished in these calls for submission. Maybe it was a ruse to pacify white anxiety—maybe not. In practice, though, Ryland allowed the 30 Black deacons (elected by Black congregants) to coordinate church activities, handle finances, regulate membership, run the administration and more with little interference. He allowed the members to elect “assistant preachers.” The white overseers, too, rarely intervened in these matters. Perhaps these glimmers of autonomy for an otherwise highly controlled community was what caused the membership of FABC to nearly double in its first year.

Ryland began his services with an opening prayer. Often, he’d call on one of the elected assistant preachers to stand up and give this opening prayer. Then, perhaps 30 minutes later, that same opening prayer was still going on, sounding less like a prayer and more like a full sermon. In this way, Black preachers slyly claimed the right to preach to Black congregants in Richmond. One of these assistant preachers Ryland routinely called upon was John Jasper, who would later gain national fame for his sermonizing and founding Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church here in Richmond.

The independent structure of the Baptist Church in general allowed First African Baptist Church to forge local partnerships and committees, pouring their resources into causes that uplifted and empowered the Black community. They formed mutual beneficial societies and aided those in poverty. With so much poverty and suffering in their own community, the church was nevertheless liberal in their charity. Members—both enslaved and free—raised money to aid the victims of the 1840s Irish Potato Famine.

One of the more extraordinary developments within the First African Baptist Church was the creation of a community court to mediate disputes and handle discipline. At the time, outside the church’s walls, a Black person was not allowed to testify in court or have a jury trial. An enslaved person could not pursue justice without the approval of a master and, even if justice prevailed, compensation went to that master. With little faith in the white-run government court system just a few blocks away, FABC members found that the justice meted out by their Black deacons was much more fair and compassionate, albeit very strict. It was also cheaper than hiring a lawyer. And so the FABC court tried cases ranging from adultery to theft to immoral dancing. They also heard complaints against insulted honor or shame. Amazingly, an enslaved congregant could seek justice for the most fundamental and yet most elusive of human rights denied to them in the outside world: dignity.

At their harshest, the FABC court could revoke church membership. While That may not seem exceedingly strict, being cast out from an institution with such reach and resources and thrown into a world where you hold no rights at all, could seem like a death sentence.

The loosely democratic structure of the church—only free males could vote—prepared some in the Black community for wider government participation. And though enslaved members could not vote on church matters, they had agitated for that right for years, which initiated them into the practice of democratic protest. So with emancipation in 1865, FABC was perfectly poised to harness and direct Black ambition during such a chaotic time. In 1867, they hired their first Black pastor, Dr. James H. Holmes, who had been born into slavery. Membership exploded and the congregation outgrew their building yet again (they had already split to create Ebenezer Baptist Church in 1858). They demolished the brick building and built a new one in its place in 1876. That building, with its grand Doric columns, still stands today, though the congregation moved to Barton Heights in 1955. With full Black control, the church fostered new generations of Black leadership—John Mitchell, Daniel Webster Davis and Doug Wilder were counted amongst its members.

But the legacy of First African Baptist amounts to much more than its illustrious members. In the radical act of fostering dignity in a population that legally had no claim to it, the church empowered everyday people to demand more for themselves and more for their community. Dignity was the first and most important step for everyone: young and old, enslaved and free, male and female. Church leaders knew this above all else.

Around 1875, the FABC Sunday school teacher noticed a dirty, disheveled little girl of about ten years old, playing on the sidewalk outside the church. He invited her to join the Sunday School and she accepted the offer, coming in for the first time, though she only lived a block away. As the teacher’s son later recalled, “The little girl liked what she found, and next Sunday, clean and neat as a pin, she came back.” The little girl who made that small yet dignified step would soon rise through the leadership ranks of the church. She’d cut her teeth there on civic, business, and political engagement. Her name was Maggie L. Walker.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | First African Baptist |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | October 11, 2023 |

| Updated | May 24, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |