John Dabney’s Mint Juleps

John Dabney earned his freedom by making mint juleps.

By Valentine Museum Staff

When Charles Dickens came to visit in 1842, his published impressions scandalized Richmonders. He criticized the squalid conditions in the factories and streets, the immorality of slavery and the willful blindness of the wealthy to the misery all around them. He did, however, praise our mint juleps. Beloved by visitors and citizens, the mint julep represented the genteel southern class in the light they wished to be seen. Even a staunch abolitionist like Dickens could not deny its charm. And our most famous mint julep, made by a local bartender named John Dabney, touched the lips of visiting politicians and royalty during this city’s darkest era. In fact, his recipe became a tool of Richmond diplomacy.

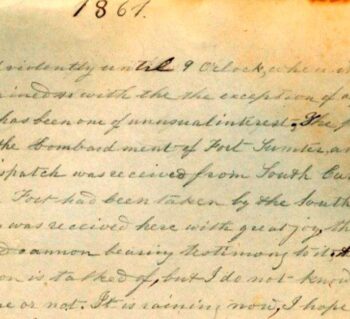

John Dabney was born into enslavement in Hanover County around 1824. Owned by Cora Williamson DeJarnette, Dabney was rented out to a relative named William Williamson, who owned a restaurant in Richmond. Williamson arranged for Dabney to be trained by chefs. He soon became well-known locally for his terrapin stew and his canvasback duck, but what really impressed people were his mint juleps. As an enslaved bartender, Dabney was allowed to keep a portion of his earnings. With those earnings and fueled by his rising fame, he bought his wife’s freedom in the late 1850s. Still enslaved himself, he kept bar at a number of fashionable restaurants during the Civil War. He had been saving to purchase his own freedom when the war ended.

As a free man, he continued to keep bar around the city. By 1868, he’d saved enough to purchase his freedom from Williamson—which he did, even though he was already free. After 41 years of bondage, Dabney found himself in a position very few freedmen did: he was so beloved by the powerful class that any Richmond bank would loan him money. With his culinary skills and sterling reputation, he opened his own successful restaurant here in the early 1870s. His son later wrote that his father’s “reputation and business standing rendered him almost immune to segregation, ostracism or racial prejudice.”

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | John Dabney’s Mint Juleps |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | November 14, 2023 |

| Updated | May 24, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |