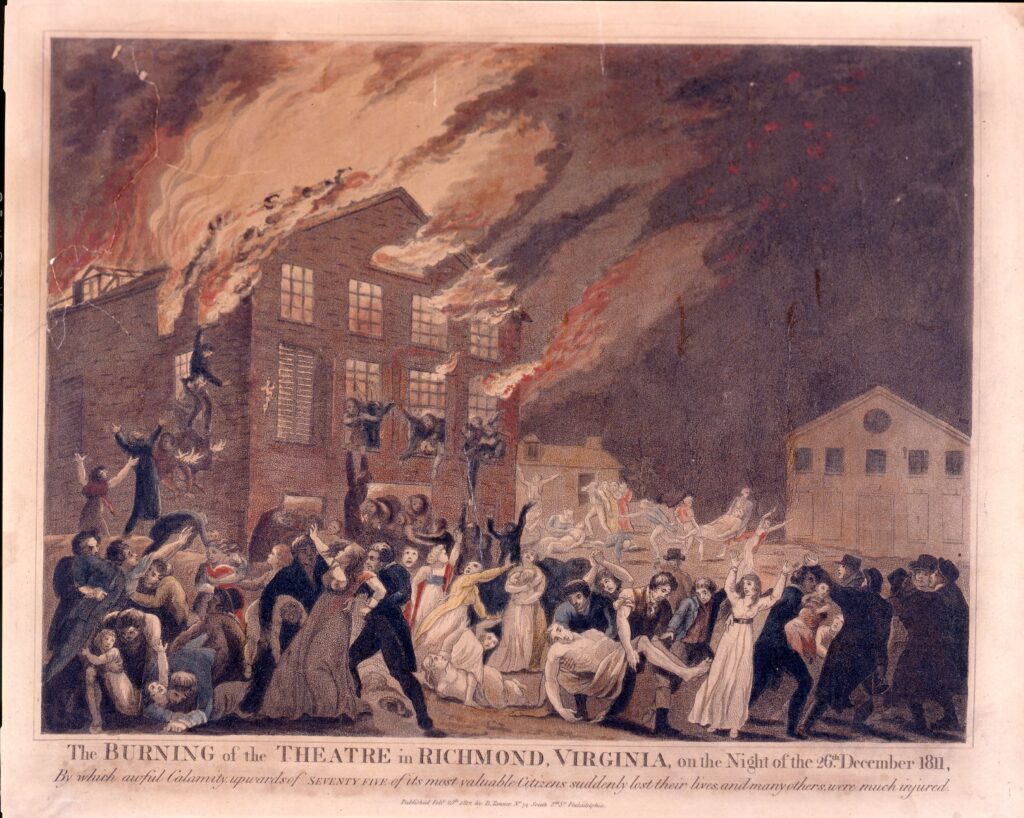

1811 Richmond Theater Fire

Richmond Theater Fire in 1811 that killed 72 people including the governor of Virginia.

By Valentine Museum Staff

In the 19th century, theater was the primary public entertainment for all socioeconomic classes, from the gentry to the enslaved. To meet the high demand and keep fresh faces and talent in rotation, traveling theater companies roamed the country, stopping for months-long stints in cities before moving on to the next place. Thus embedded in a city for a season, the actors and actresses became temporary citizens and minor celebrities among the population.

In August of 1811, the Placide and Green Company, from South Carolina, arrived for a season in Richmond. Among them was an English actress named Eliza Poe. At the Richmond Theater at Broad and 12th Streets, the company performed different plays several nights a week. Wealthier Richmonders paid a dollar to sit in front of the stage, or in suspended boxes above the crowd. Less well-to-do attendees, including the enslaved, could sit in the balcony for 25 cents. A typical night’s entertainment could last five hours, with two full-length plays separated by short skits.

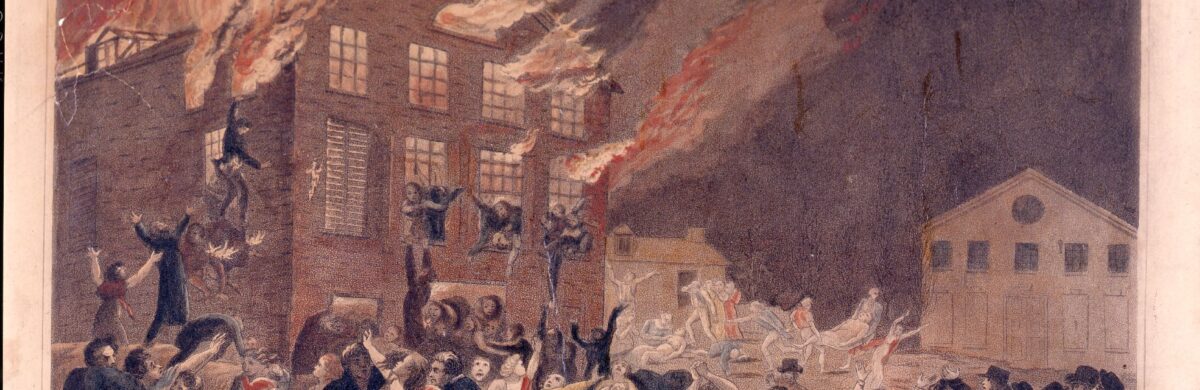

The Richmond Theater seated 500, though the December holiday season strained its capacity. On December 26, with the General Assembly in session, the evening’s performance had drawn 600 spectators to the 3-storey brick theater. In a town of only 10,000, that was 6% of the population. State legislators and even the Virginia Governor George W. Smith came. The second play that night was a “pantomime”—a musical slapstick production—called The Bleeding Nun. For this, 80 children were also in attendance for the performance that would quickly become the deadliest urban disaster in American history at the time.

After the end of the first act of The Bleeding Nun, a crew member accidentally raised an onstage chandelier that had not been snuffed out. The flames caught on 34 suspended hemp backgrounds, painted with oil. Within a few minutes, the roof of the theater was engulfed in flames.

The poorly designed theater had few exits. The discount seats in the balcony and the stage had separate doors, but those on the floor and in the boxes could find no easy way out. The fire spread so fast and became so hot so quickly that witnesses claimed people died in their seats, overcome by shock. The wealthier patrons in the upper boxes packed the only small staircase, which collapsed. Historians estimate that the temperature inside rose to 1,000 degrees. In the chaos, trapped on the second and third storeys, burning people threw themselves out of the windows.

Despite acts of heroism by both the enslaved and the elite, rescue was utterly impossible for many of those trapped. The entire building burned to the ground too quickly. Seventy-two people died in the Richmond Theater that night—including 54 women and girls.

Gilbert Hunt, an enslaved man who personally rescued 12 women from the upper windows, returned to the scene the next morning: “There lay, piled together, one mass of half-burned bodies—the bodies of all classes and conditions of people—the young and the old, the bond and the free, the rich and the poor, the great and the small, were all lying there together.”

Governor Smith was only identifiable by a stock buckle.

A stunned city went into mourning as news of the horrific disaster spread around the world. With so many of the dead burned beyond recognition, the victims were all entombed together on the spot, over which Monumental Church was soon built as a memorial. Richmond officials prohibited any plays, balls or assemblies for four months in respect for the dead. With their contract thus cut short, the shocked, embarrasse, and traumatized Placide and Green company quickly cleared out of town.

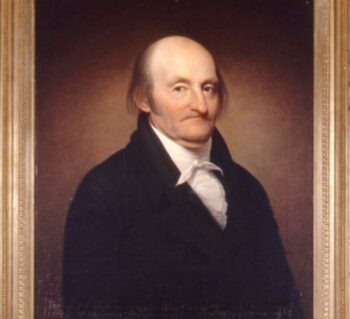

They did, however, leave one person behind. Just a few weeks before the fire, one of company’s star players, Eliza Poe, had died of an illness in a boarding house here. he left behind a three-year-old boy named Edgar. A prominent local family, the Allans, adopted him and made him a wealthy Richmonder overnight. Many believed this to be a fortunate turn for the impoverished orphan, though perhaps Richmonders could never quite shake his association with so much death and destruction. Perhaps that shadow followed him all of his life.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | 1811 Richmond Theater Fire |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | December 23, 2020 |

| Updated | May 28, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |