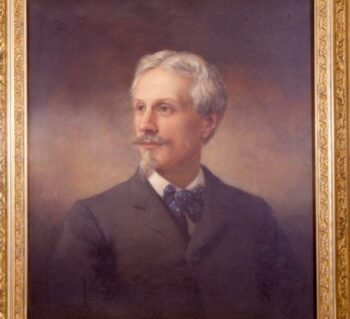

Dr. James McClurg: Richmond History Maker

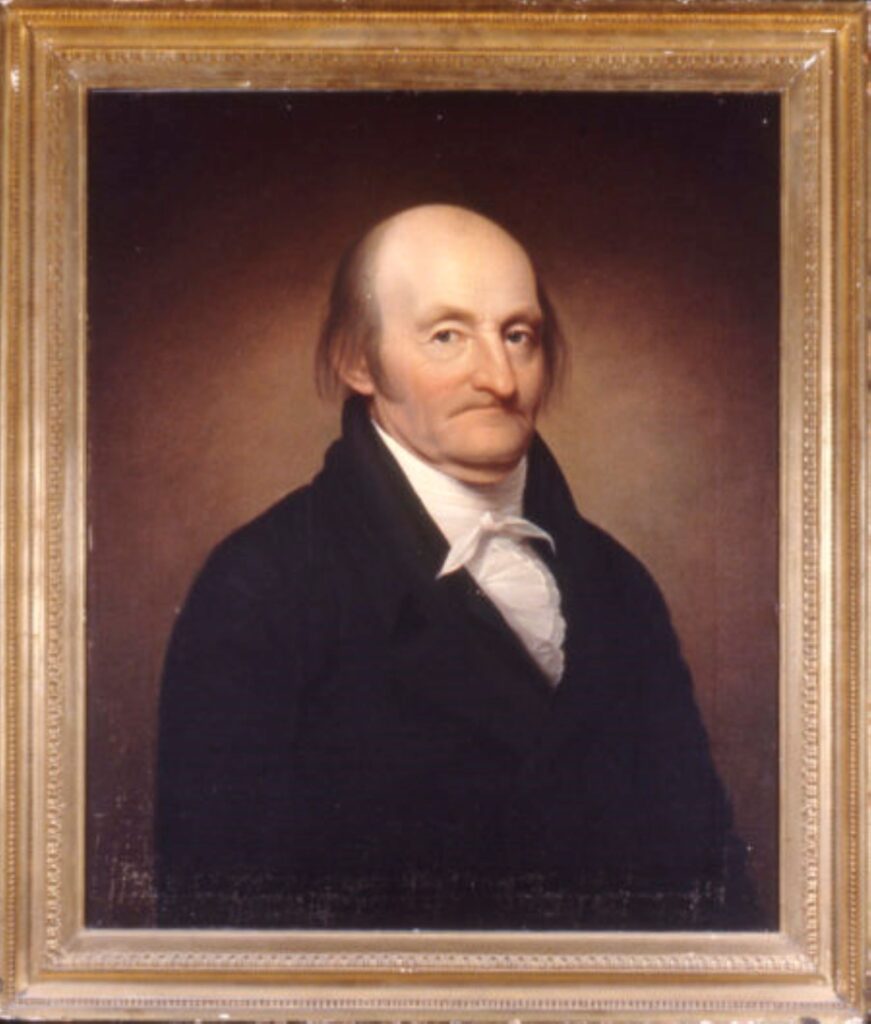

Doctor James McClurg, Elizabeth Wickham's father, left the Constitutional Convention without signing the final document.

By Valentine Museum Staff

Most standard biographies of Doctor James McClurg (1747-1823) begin with his accomplished medical career, friendship with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison and mention his participation in the American Revolution as a physician. Some detail his attendance at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, noting that he left without signing the final document.

It is clear that James McClurg did not leave the Constitutional Convention in late July 1787 because he opposed slavery. He and the other Virginians at the summer-long meeting in Philadelphia supported preserving the domestic slave trade. Instead, they worked to ensure that an enslaved individual would count as only 3/5 of a free person in order to determine representation in Congress.

So why did he leave? After months of working on the document, McClurg disagreed with the length of the President’s term (he thought it should be for life), and he believed the federal government should be able to veto state laws. He and James Madison exchanged letters about these issues. Madison sent him a copy of the Constitution in October 1787.

McClurg was a Federalist, meaning an advocate for a strong central government that would oversee the then-13 states. He and the other delegates created a document that provided structure and simultaneously crafted a process to amend it. After ratifying the initial Constitution in 1788, the states set about changing it immediately, adding ten amendments largely based on the proposals of Virginia’s George Mason. But the Bill of Rights (ratified on December 15, 1791), as revolutionary as it was, still did not apply to McClurg’s enslaved man and women. They could not enjoy freedom of speech or assembly. They certainly were not allowed to petition the government to redress their grievances.

Thirty-eight delegates* signed the final draft of the Constitution on September 17, 1787. It would be 74 years before the 13th Amendment abolished American slavery in 1865. Three years later, the 14th Amendment provided citizenship and equal protection for those persons born or naturalized in the United States. In 1870, the 15th Amendment gave the vote to men, no matter their “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

We can honor the living, breathing document that James McClurg and his colleagues created and expected to be altered while also acknowledging the harsh reality of James McClurg’s endorsement of and participation in the slave trade.

*George Read signed for an absent John Dickinson. 39 signatures were added by 38 men. Three Virginians signed the Constitution: George Washington, John Blair and James Madison.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | Dr. James McClurg: Richmond History Maker |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | October 11, 2023 |

| Updated | May 24, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |