Battle of Bloody Run

The Battle of Bloody Run was a colonial battle that took place in Richmond 364 years ago in the Church Hill area.

By Valentine Museum Staff

This conflict shed a light on the ever-evolving and increasingly complicated relationship between colonists and native peoples, which resulted in a tragic battle and a speech before the General Assembly by Pamunkey Chief Cockacoeske.

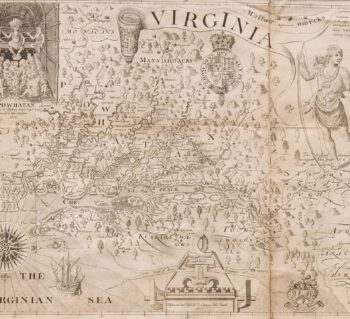

In 1656, the Westo tribe from the Lake Erie region settled at the falls of the James River. In a region already crowded with fragile and ever-changing alliances between tribes and settlers, friction began almost immediately. The General Assembly charged Colonel Edward Hill of Shirley Plantation with peacefully removing the newcomers: “they shall first endeavour to remoove the said new come Indians without makeing warr if it may be, only in a case of their own defence.” Invoking the 1646 peace treaty that ended the Third Anglo-Powhatan War, the Assembly asked 100 men from the Pamunkey tribe to assist Hill. Pamunkey Chief Totopotomy complied with the request.

Colonel Hill flouted the General Assembly’s instructions and ordered the Pamunkey soldiers to immediately attack the Westos. The ensuing battle was so intense that witnesses claimed a nearby creek ran red. Hill ordered his colonial soldiers to retreat, completely abandoning his native allies. Nearly all the Pamunkeys were killed, including Totopotomy. Upon his death, his wife, Cockacoeske, became chief of the Pamunkeys. She never forgot the battle or the colonists’ broken promises.

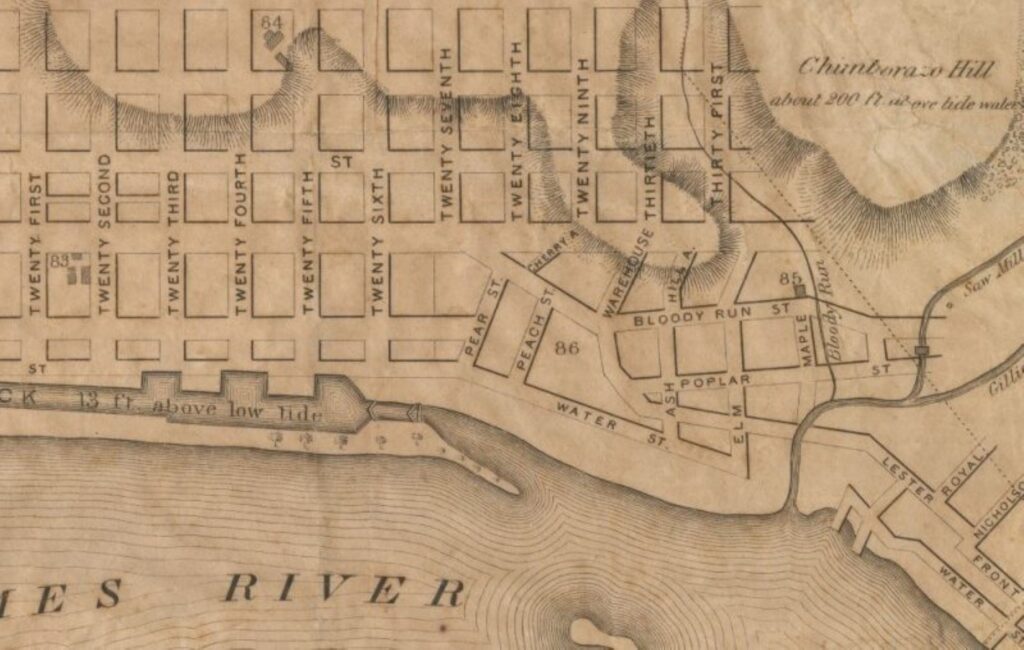

The creek at the site of the conflict was renamed Bloody Run. It flows south between what is now North 30th and 31st Streets, around Chimborazo Park, before joining Gillies Creek. The ravine between Chimborazo Hill and Libby Hill marks its old path. In the 1880s, like most creeks in city limits, it was buried and eventually incorporated into Richmond’s combined sewer system.

Twenty years later, in 1676, when the colonists asked for Pamunkey defense amid rising tensions with other tribes, she delivered a speech before the General Assembly, reminding them of their betrayal during the Battle of Bloody Run. She sent only twelve men. Just weeks later, Nathaniel Bacon declared himself a general in a new government. In rebellion against the governor, he marched his small army to the Pamunkey settlement on the Rappahannock River. There, he attacked the settlers’ closest ally among all the Virginia tribes. Pamunkey veterans who had fought alongside the colonists for thirty years found themselves yet again fighting against them.

The difference between history and lore often lies in the lack of nuance. When events are simplified, the true messiness of history can be lost. American Indian history has suffered from such reductive treatment. Two simple yet contradictory versions of colonist/native relations have long been accepted: either the groups are sharing a friendly Thanksgiving feast or they are at war with each other. In reality, as we can see above, the history is much more complicated.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | Battle of Bloody Run |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | November 25, 2020 |

| Updated | May 28, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |