Jane King: The Ice Queen in the Sweltering South

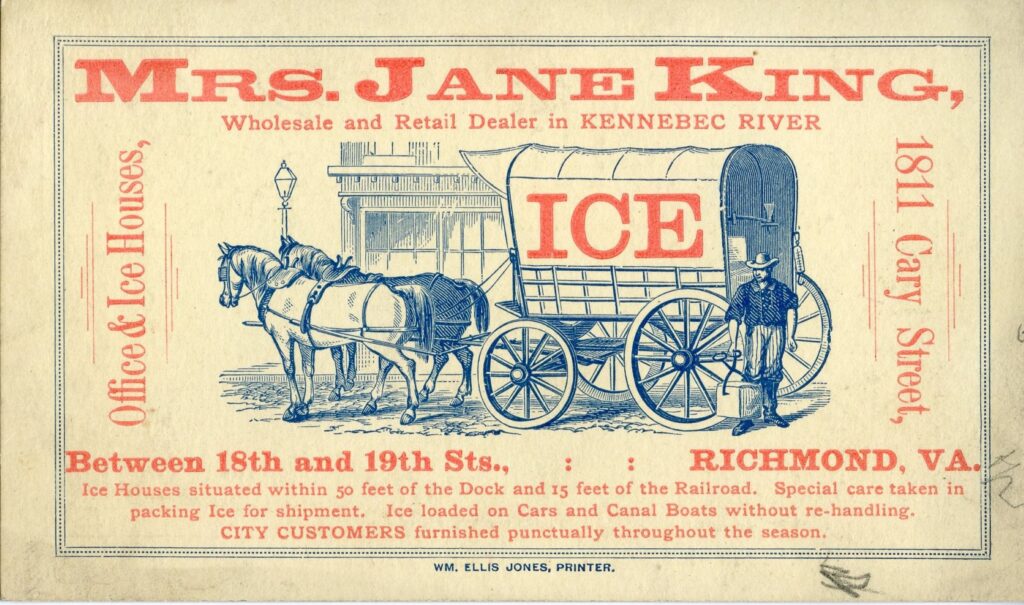

Not until 1856 did regular Richmonders have access to a truly cold drink on a summer day. The luxury was brought to us by David King, an immigrant from Northern Ireland, who opened an office and ice house at 1811 East Cary Street. At his dock on the Kanawha Canal, he began to receive schooners from Maine, loaded with frozen slabs of the Kennebec River.

By Valentine Museum Staff

That’s right—the first commercial ice available in Richmond was shipped all the way from Maine. Twenty-inch slabs sailed hundreds of miles down the seaboard, up the James River and into the canal. They were then stored in a huge hole in the ground so they would not melt in our summer heat. Ice from the Kennebec River had a reputation for sparkling clarity and cleanliness. Despite this, and despite its obvious allure to a sweaty southern city, ice was not immediately popular here. The cost made it inaccessible for many. Also, palates that had been drinking lukewarm or hot beverages for a lifetime were probably unaccustomed to the switch. Ice was largely used by restaurants, hospitals and the wealthy in the antebellum era. Drivers delivered the slabs by horse-drawn wagon. King had enough business to keep him afloat until the Civil War, in which he fought on the Confederate side. But he returned from the First Battle of Manassas sick. He was unable to keep up with the increasing demands of the ice business.

Too ill to work, David King left the operation of his ice business to his brother-in-law, John McGowan. King died in 1872, as his family knew he would. He left a widow and seven children. But in 1874, the family received another blow, this one a complete surprise: John McGowan died suddenly, in July, at the height of the ice season. With this, King’s widow, Jane, needed a new person to run her family’s business if she was to keep herself and her seven children fed. But the ice business was tricky and required much foresight and experience. Contracts with Maine suppliers were signed in early winter, without any clue of the next season’s weather. Everyone lived in fear of a mild Maine winter or a sweltering Virginia summer. And the product itself was as volatile as the business. She very quickly decided that the person to run the ice house must be herself.

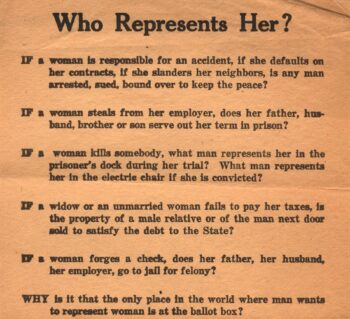

Jane King had worked behind the scenes at her husband’s business, mostly as a bookkeeper. She knew the business well, though she also well knew the prejudices she would face. Few male workers, let alone sea captains, would take orders or do business with a woman in the 1870s. On top of that, an economic depression had taken hold in 1874 and her brother had taken out a new mortgage on the canal-front property right before he died.

At the age of 44, Jane King determined that the only way to step into the role of an ice dealer was to do so boldly. She reopened under her name and took out a color ad on the front cover of the 1875 city directory: MRS. JANE KING DEALER IN ICE.

Soon after Mrs. Jane King took over the ice house, she met a captain on her dock and told him where and how to unload. He refused to do anything a woman told him to do. She then refused to pay him. The stand-off ended quickly in her favor. In another instance, a crew grew so irate at her audacity to be a boss that they poured varnish over the ice they had just delivered. She docked the value from her payment. Predictably, men in the business began calling her the Ice Queen behind her back, as she remained cool and firm and businesslike through these protests. She earned a reputation as a serious businesswoman who would not be cowed. Within two years of taking the helm, the family business was out of the red.

Jane King did more than keep the ice house running. She expanded and thrived, even as ice’s ever-growing popularity brought on competitors. One main rival, Richmond Ice, opened in 1881. They alone received over 100 ice schooners a year and could store 3,000 tons of ice in a mammoth hole on Canal Street. To stay competitive, King innovated and embraced new technologies. With the rise of the railroads, she took full advantage of the tracks alongside the canal and began to ship ice not only around Virginia, but into West Virginia and the Carolinas. To beat competitors’ prices, she began storing her own winter ice from a spring pond on her suburban farm. She called it “country ice” and sold it at a 20% discount. She diversified with a coal and wood yard, to keep business strong in the winter months. An early adopter of the telephone, she was the first woman in the city to have a phone line in her name and the only woman listed in the city’s first telephone directory.

In 1881, King bought 205 N. 19th Street, one of the most illustrious homes in Richmond (still standing and now known as the Pace-King House). Her new home had two indoor bathrooms and running water in all the bedrooms. Living in luxury, she also maintained high standards for her product. If she noticed dirty ice coming off a ship, she let the captain know that he should clean his hold. If a railcar went astray and her ice melted, she made good use of her phone and collected damages from the railroad company. Her reputation for coolness came from the fact that she did not raise her voice in argument, though she did not shy from pursuing wrongs via lawsuits. By 1892, the operation had grown 700% and employed 30 men, and owned 14 ice wagons, seven coal wagons and 40 horses.

In nearly 40 years, the basic logistics of the ice business changed very little. Sailed in from Maine, unloaded by crews, stored in the ground, and delivered by wagon; the slabs kept food fresh, hospitals running and Richmonders cool. But a fundamental change did come in 1892, virtually overnight: an artificial ice plant opened here. The whole business model crumbled. Suddenly, ice could be made in vast quantities, onsite and on-demand. Without ice cutters in Maine, without ships, captains or docks, without gargantuan holes in the ground. Without living in fear of the weather. In response, Jane King did not balk. Before anyone else could do it, she contracted the entire output of the factory and stopped shipping from Maine entirely.

No amount of savviness could hold off the machine age. And it would not be long before more artificial ice plants sprang up in Richmond. The traditional ice companies needed to slim down and band together to survive. Only three years after artificial ice came here, in 1895, King and her three main competitors merged. King retired on a very generous stipend.

King’s career no doubt inspired other Richmond women who would pursue their own businesses. She obviously did not rid this city of prejudice. As soon as she knocked down a barrier, it essentially went back up for the next generation. This was the 19th century, after all. But you do not need to change an entire culture to affect change. Her most lasting impact, as evidenced by her nickname, was her behavior in the face of discrimination. She taught women how to succeed despite the culture. After shying away from a fistfight, King’s grandson once recalled her response. “Hold your own,” she scolded him. “Never back down.” It was the reason, after all, for her own success.

Sources

Much of the information for this blog post is from a the article “Ice Queen” by Helen Milius, published in the December 1959 issue of The Commonwealth.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | Jane King: The Ice Queen in the Sweltering South |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | November 13, 2023 |

| Updated | May 24, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |