Equal Suffrage League of Virginia

On November 27, 1909, a group of prominent white women met in a Richmond home to establish a statewide suffrage organization.

By Valentine Museum Staff

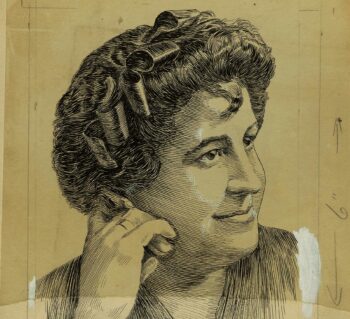

Named the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia, they elected Lila Meade Valentine as their president. Their mission was to “educate” Virginians and Virginia’s legislators on the merits of women’s suffrage. Like all good educators, they were strategic, creative and tireless in their methods. For easy access to the halls of power and the public, they established headquarters at 802 East Broad Street—just blocks from both the Capitol and the busiest commercial district in the city. From there, audiences were easy to capture.

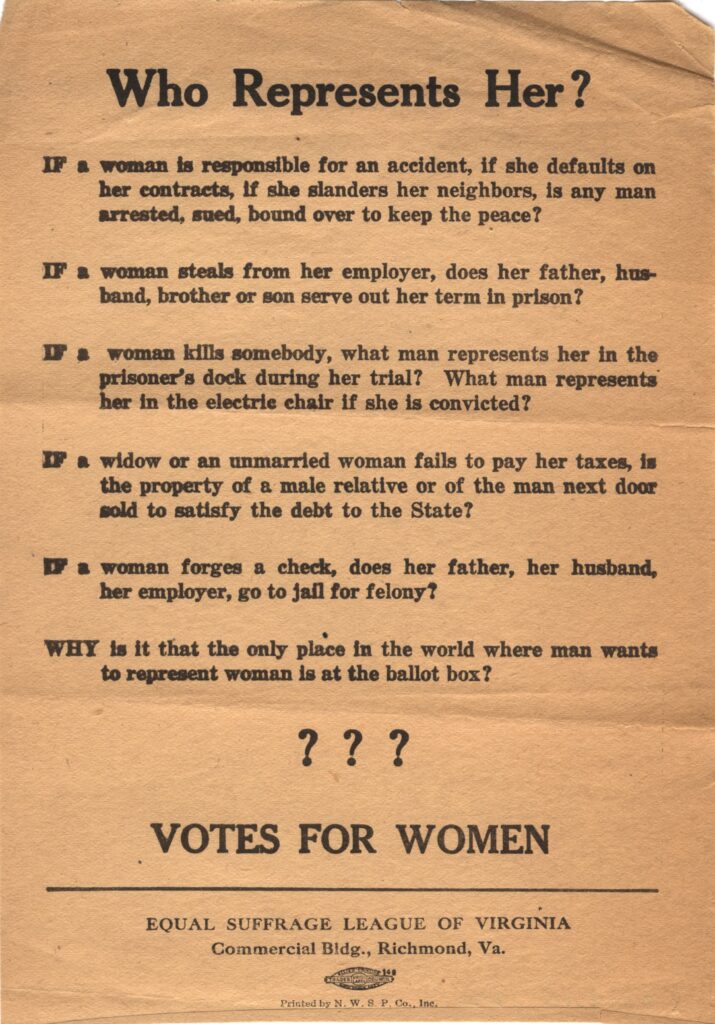

Out in the streets, they distributed flyers both serious and humorous. To reach people in their homes, artistic members such as Nora Houston designed postcards. The writers—Ellen Glasgow and Mary Johnston—wrote editorials. Adele Clark, another artist, even used trickery to spread the message. With a paintbrush in hand, she’d set up her easel on Broad Street. After an unwitting crowd formed to watch her paint, she turn from her canvas and begin to canvass for the cause. The Equal Suffrage League became hard to ignore as they traveled to schools, took over street corners, haunted legislative sessions, attended union meetings, marched in parades and even set up booths at the state fair. By 1914, the League had grown to 45 local chapters. By 1916, they reported 115 local chapters statewide.

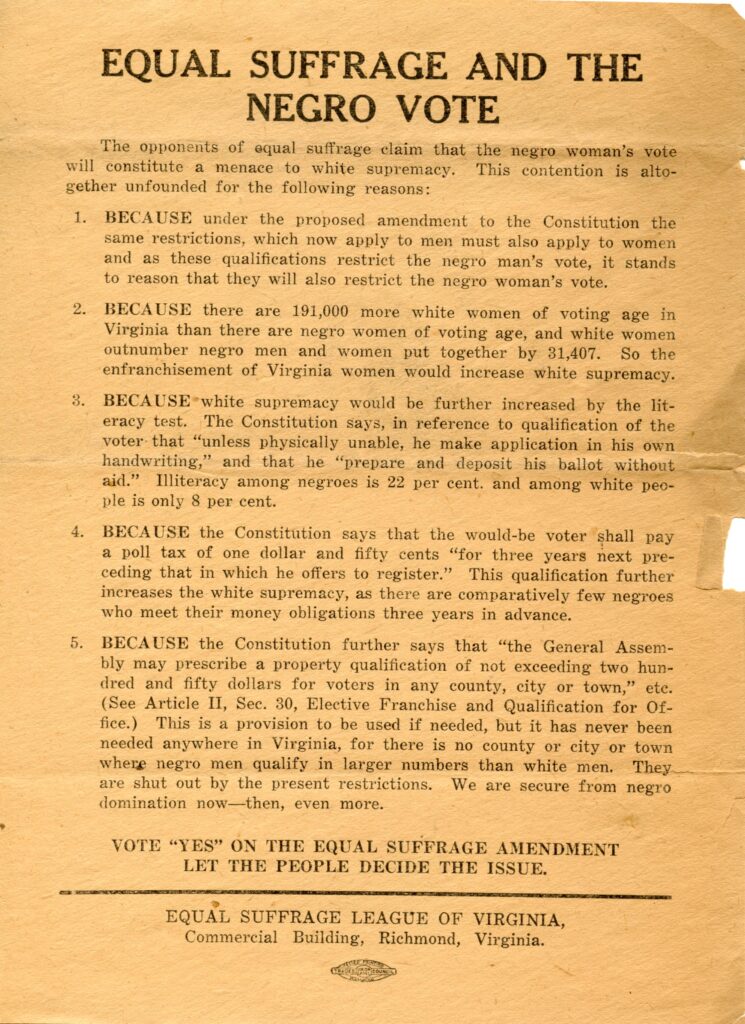

As a state-focused organization, the League aimed to gain suffrage through changes in the state constitution. But despite their multi-faceted efforts, the Virginia legislature rejected suffrage resolutions three times between 1912 and 1916. Some League members became frustrated and shifted their efforts to national organizations that lobbied the U.S. Congress for a Constitutional amendment. Others continued to press on at the state level, where they confronted the anti-suffragists’ escalating war of words. In Virginia, and across the South in general, many feared the unintended consequences of enfranchising Black women. With Black men and Black women at the polls, they argued, whites might lose power. In response, the League sought to allay those fears by embracing racist laws, positions and rhetoric. They printed more “educational” flyers, such as the one below, which assured nervous whites that white supremacy would, in fact, be strengthened by female suffrage.

Of course, the suffragists eventually won at the national level. When the Constitutional amendment passed Congress in 1919, the 32,000-member League poured their energies into the campaign for ratification. The amendment failed in both houses of the state legislature, however, by a large majority. It would not pass for more than 30 years. Only in 1952 did the General Assembly formally, perhaps begrudgingly, ratify the 19th Amendment. But none of this mattered much once enough states signed on by August of 1920. Within two months, and in time for the 1920 Presidential election, more than 10,000 white women and nearly 2,500 Black women had registered to vote in Virginia.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | Equal Suffrage League of Virginia |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | October 12, 2023 |

| Updated | May 24, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |