Lillian Payne and the Independent Order of St. Luke

“Who is so helpless as the negro woman? Who is so circumscribed and hemmed in—in the race of life, in the struggle for bread, meat, and clothing—as the negro woman?”

By Valentine Museum Staff

In 1901, when Maggie Walker made this statement, Black women in Richmond had few employment opportunities outside of domestic service, factory work or agricultural labor. Walker, the daughter of a laundress, once claimed that she herself had been born with “a laundry basket on my head.” Her mother’s endless hours, and the painful scrubbing with grated skin and harsh chemicals had made a deep impression on her. And though her public education spared her from this fate, the best job society could offer an educated woman—Black or white—was that of a teacher. Walker did teach but was forced to retire when she got married.

The double bind of racism and sexism that Black women experienced compelled Walker to create new economic opportunities when she took over leadership of the Independent Order of St. Luke in 1899. At the time, it was a beneficial society for burial insurance. But under her leadership, the IOSL expanded into Black banking, Black publishing, Black retail and other ventures meant to service an underserved community.

Black women were the driving force of that expansion. Some departments within the organization were advertised as being run exclusively by women. Walker, in fact, was not the only woman to succeed within St. Luke Hall. Many others —Lelia Bankett, Emeline Johnson, Ella O. Waller—many not be so well known, but were still vital to the victories of the Independent Order of St. Luke. And they proved to a sexist and racist world that successful Black women were not an anomaly, but an inevitability.

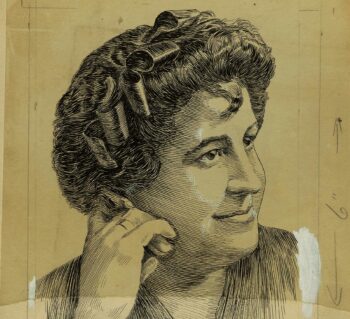

One of the many women instrumental to the IOSL’s success was Lillian Payne, a lifelong Richmonder. A former teacher like Walker, she came into the organization’s employ in 1900. Over a career there that lasted more than 50 years, Payne served in many roles, including financial secretary, home office manager, managing editor of the St. Luke Herald and director of the St. Luke’s Penny Savings Bank. At the bank, she led the Finance Committee, which underwrote thousands of mortgages for Black Richmonders. With a creative side as well, she also wrote and directed many of the IOSL’s public pageants.

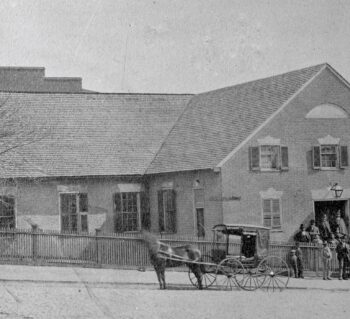

Payne’s work on the weekly St. Luke Herald, however, would be her most powerful contribution to the IOSL. The Herald was written, edited and printed at IOSL headquarters. As a clerk in the St. Luke’s Printing Department, Payne corrected the first proof of the first edition in March of 1902.

Initially, the purpose of the paper was to communicate and coordinate IOSL matters across an expanding number of councils across the nation. But in 1902, the same year the paper launched, Virginia lawmakers rewrote the state constitution, disenfranchising Black voters. The Herald responded with its first editorial, which laid out the new publication’s mission: to fight. The staff vowed to fight Jim Crow, voter suppression, educational suppression and all forms of racial injustice. Within five years, Payne rose from first clerk to managing editor.

As they spread awareness of racial injustice and coordinated economic boycotts, Payne and the St. Luke Herald’s staff also amplified the IOSL message of economic uplift, advertising benefits and opportunities within the organization. With Payne as manager, the next decade brought in thousands of new subscribers. By 1929, the IOSL had 100,000 members in 24 states and the Herald became Richmond’s leading Black newspaper, with 30% of Black Richmond families subscribing.

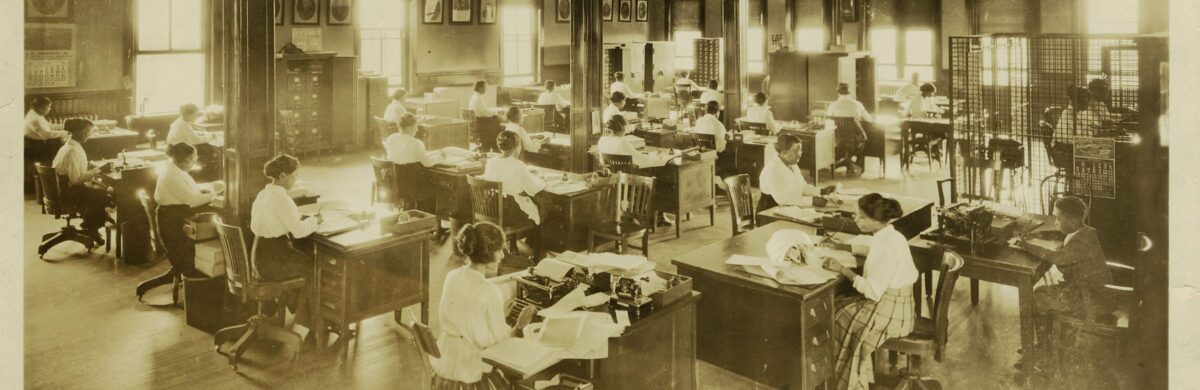

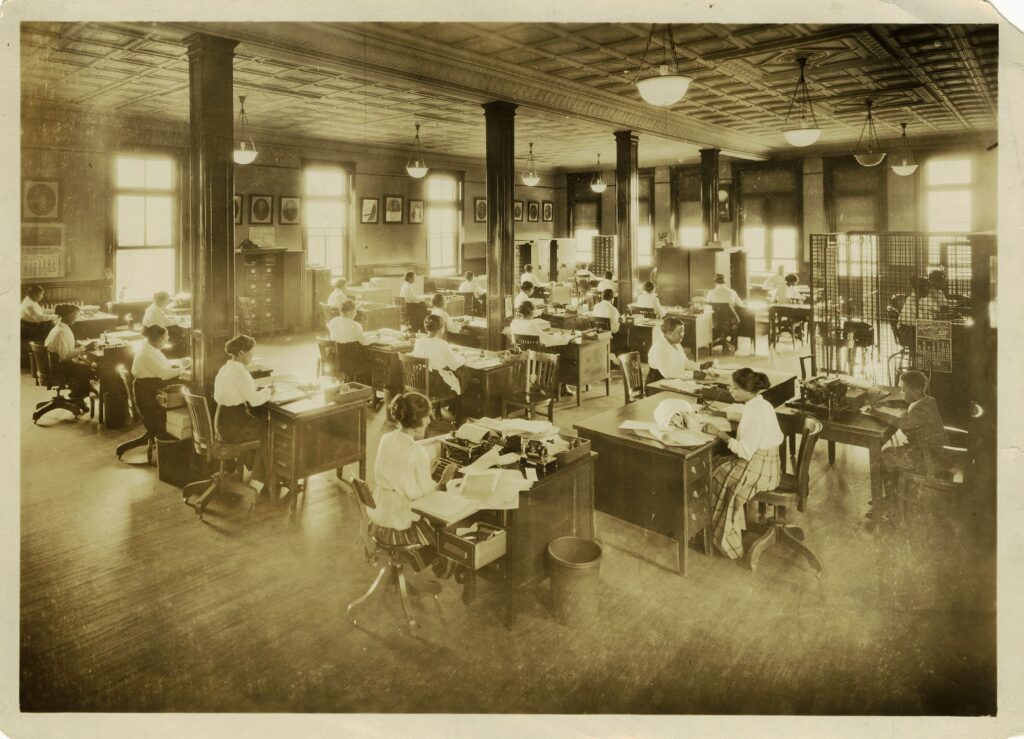

As a newspaper editor and bank director, Payne had attained power, influence and success rarely available to even white women at the time. Her rise was made possible by the visionary, feminist employment structure of the IOSL, which sought to untie the double bind of sexism and racism. But the most impressive feat of the organization may not be its wildly successful women leaders like Walker and Payne. Perhaps even more revolutionary, though much more subtle, was the chance the IOSL gave to a larger number of ordinary Black women, who did not have the educational opportunities that they had had.

By the early 20th century, educational opportunities for Black Richmonders had dwindled since the Freedmen’s era of the 1870s. Despite this, the IOSL made it possible for Black women who wanted to live ordinary lives to earn a good living in respectful and respectable jobs. In the 1920s, you could walk into the St. Luke Hall on a weekday and see more than 50 Black women working away: clerks, assistants, stenographers, field employees, recruiters, community organizers, accountants, underwriters and cashiers. From there, a substantial Black middle class began to rise in Richmond.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | Lillian Payne and the Independent Order of St. Luke |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | October 11, 2023 |

| Updated | May 24, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |