Richmond’s Monument Avenue: Memorializing the Lost Cause Myth

Richmond’s Confederate monuments on Monument Avenue supported the Lost Cause myth and dominated the city’s monumental landscape more than 130 years.

By Valentine Museum Staff

As the former capital of the Confederacy, Richmond’s political and business leaders erected these monuments of public memory putting the message of the Lost Cause myth front and center for more than a century.

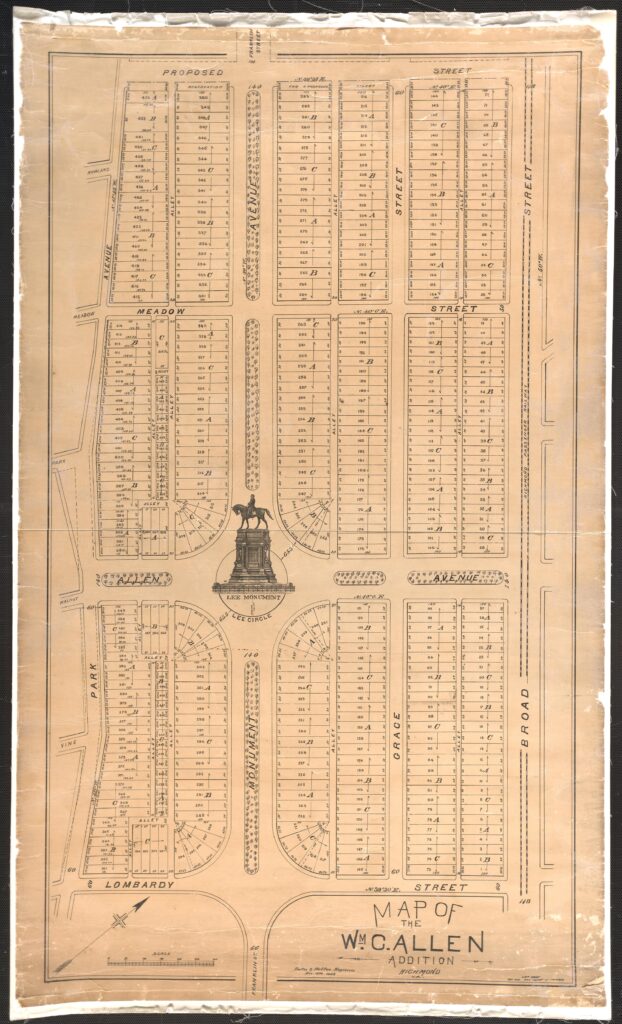

In the 1880s, local landowner Otway Allen realized that if he donated land for the Robert E. Lee Monument, wealthy white Richmonders would then want to live in proximity to such a prestigious landmark. Allen developed Monument Avenue, selling residential lots to doctors, lawyers, bankers, real estate developers and businessmen, who hired architects to build their houses. The section of Monument Avenue between Lombardy Street and the Arthur Ashe Monument showcases the work of approximately 30 architects and various architectural styles, including Queen Anne, Italianate, Richardsonian Romanesque, Jacobean, Stick and Shingle. With a few modern exceptions, these houses were all built between 1902 and 1931.

As the city expanded, so did the number of monuments to the Confederacy set among grand residential homes.

Robert E. Lee’s statue on Richmond’s Monument Avenue was dedicated in 1890, 25 years after the end of the war. His towering 60 feet high statue paved the way for four additional Confederate monuments on Monument Avenue (James Ewell Brown Stuart and Jefferson Davis in 1907, Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson in 1919 and Matthew Fontaine Maury in 1929) and many others throughout the city.

Most of Richmond’s Confederate monuments went up in the early 20th century during the rise of the Jim Crow era to send a clear message that white Richmonders were in control of the city’s political and economic structures. By the 1970s, the city’s politicians were more racially diverse. And in 1996, the city unveiled a monument to Richmond tennis star and humanitarian, Arthur Ashe, on Monument Avenue.

There have been community discussions over the years about how to deal with these Lost Cause monuments. Should they be taken down? Should we add information to explain the history behind their creation? Do these monuments that were created to divide us reflect our collective values today?

“Monument Avenue is one of Richmond's most beautiful streets...But my fellow Richmonders, something is wrong with this picture. It's the story told by the Confederate monuments that give the street its famous name and have defined its landscape for more than a century. That story is, at best, an incomplete story - equal parts myth and deception. ”

In the summer of 2020, the discussions turned to action amid protests in Richmond and around the nation reacting to the death of George Floyd. On June 10, a group of social justice activists pulled down the Jefferson Davis statue on Monument Avenue. Richmond’s mayor moved quickly to remove the remaining city-owned Lost Cause statues on Monument Avenue with the exception of the state-owned Lee statue, which did not come down until 2021 after an extended legal battle decided by the Supreme Court of Virginia.

Take a look at the rise and fall of these Lost Cause monuments on Monument Avenue in Richmond.

Robert E. Lee monument (1890-2021)

James Ewell Brown Stuart (1907-2020)

Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson (1919-2020)

Sources

- Birth of Monument Avenue, Google Arts & Culture, https://artsandculture.google.com/story/birth-of-monument-avenue-american-civil-war-museum/QgXhK5dKZ1esJA?hl=en.

- Monument Avenue Commission Report, July 2, 2018, https://richmond.com/monument-avenue-commission-final-report/pdf_98dfbab1-3a10-52d4-ab47-f4a2d9550084.html.

- Kathy Edwards, Esme Howard, and Toni Prawl, Monument Avenue: History and Architecture (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, Historic American Buildings Survey, 1992),https://archive.org/details/monumentavenuehi00edwa/page/n5/mode/2up.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | Richmond’s Monument Avenue: Memorializing the Lost Cause Myth |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | October 6, 2023 |

| Updated | May 24, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |