The Early Valentine Museum, 1898–1930

Essay: The Valentine Museum opened in Richmond on November 21, 1898. Fifty years earlier, museum founder Mann Satterwhite Valentine II (1824-1892) noted: “Today I thought of procuring relics of all places dear to my memory.”

By Kate Sunderlin

Ph.D., Co-Curator of Sculpting History: Art, Power, and the “Lost Cause” American Myth

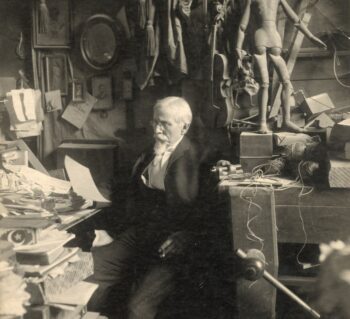

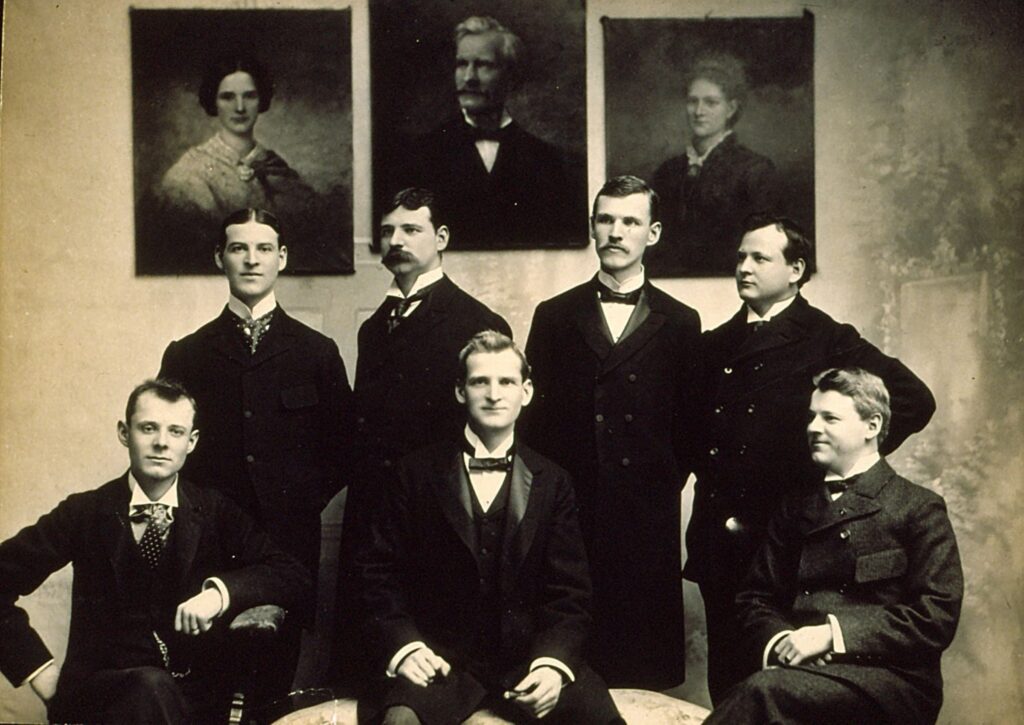

Over time, Valentine assembled a collection of art, archival, ethnographic, and history objects that he displayed in his home at 11th and Clay streets. When he died in 1892, he directed his brother and sons to open up the home as a museum for the public and left a $50,000 endowment to support it. When it opened, the early Valentine museum presented the world as its founder and his family understood it, and as they wished it to be. Edward Valentine (1838-1930), Mann’s brother, was the museum’s first president, and his nephews established two dominant narratives in the museum: the myth of the Lost Cause and more broadly their mistaken belief that white European cultures symbolized progress and superiority over Indigenous, African, Asian, and other cultures. It is not a coincidence that this museum opened in the late 1800s and remained largely unchanged until the 1920s at the same time that Virginia imposed restrictive and racist legislation on its citizens.

Assembled by Mann Valentine II, his sons, and his brother, Edward Valentine (the museum’s first President), the far-ranging collection of the early Valentine Museum was divided into several departments spread over the basement, first, and second floors of the museum. It was all housed in the former private home of Mann Valentine, an early Federal house originally built for John Wickham, which Valentine purchased in 1882. After entering the museum through the Entry Hall, guests passed through the Library, holding Mann’s collection of approximately 3,300 books, before entering to the Department of Engravings. The collection included examples of several different types of engraving, a collection of autographs, with the signatures of such notable figures as Goethe, Voltaire, P.T. Barnum, Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and others as well as several of Edward Valentine’s portrait busts of Beethoven and Confederate generals. Visitors were meant to literally and figuratively look up to these figures.

From the Department of Engravings, moved to the room devoted to “The Relics of Virginia,” which contained old furniture and mahogany cabinets filled with “china, glass, and silver that was in use in Virginia in the antebellum days.” The room also held letters, manuscripts, newspaper articles, and objects related to historic figures such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Randolph, Robert E. Lee, and Stonewall Jackson. Taken together, these texts, objects, and portraits presented a history of Virginia that preserved and the Valentine family’s desired world order. It was a visual and physical interpretation of the portion of the Lost Cause narrative that linked significant figures from the Revolutionary era, like Washington and Jefferson, to Confederate figures, like Lee, was a way defending the 1860s rebellion to preserve slavery merely as a matter of states’ rights.

The narrative privileging white, European cultures continued in the Tapestry Room, which featured a large Brussels carpet as well as copies of Greek statues, and then in a room devoted to the “relics” of the Confederacy. An 1898 newspaper reporter noted the Valentine family’s desire not “to seem even to lay claim to any of the interest which rightly attaches to the Confederate Museum,” but assured readers the museum still displayed a host of objects “which will be sure to appeal to the eye and sentiments of the present and succeeding ages.”

After this, visitors went up to the second floor and the Department of Archaeology, which largely held Indigenous objects collected by Mann S. Valentine II and his sons. The second-floor gallery housed an assortment of objects from Egyptian and Assyrian seals to Etruscan vases to “pieces of an Egyptian mummy” to “Mexican figures.” All three rooms of the Archaeology Department were laid out sequentially and guests could easily move from one room to the next before passing through a short hallway back into the second-floor gallery.

In the 1870s and 1880s, Mann Valentine II and his sons Granville, Mann III, Benjamin, and Edward Pleasants began amateur excavations of Monacan and Cherokee burial sites located in Virginia and North Carolina. The belief that Native Americans were a “vanishing race” affected policymaking and allowed for practices that were devastating to Native Americans. The ascendance of scientific racism, the (willful) misunderstanding of new discoveries and advances in scientific fields like genetics, lent a factual nature to such beliefs. Such beliefs tied into the fields of anthropology, archaeology, and ethnography through “salvage anthropology” (or “salvage ethnography”) which drove white anthropologists, archaeologists, and ethnographers in the field to excavate (and downright steal at times) objects from Native American sites in the interest of preserving their history. The Valentines and other early archaeologists never acknowledged or recognized that their policies and practices of settler colonialism were driving the destruction and disappearance of Indigenous communities and culture.

The second-floor Department of Archaeology prominently displayed ancestral remains and funerary objects stolen from Monacan and Cherokee burial sites in the early Valentine Museum. A smaller number of objects came from Arkansas, the Zuni and Pueblo Indians, Tennessee (a carved head), Ireland (Stone Age implements), and British Columbia, collected and donated by Edward P. Valentine. By displaying these remains so systematically and by placing them into the larger symbolic system on display in the museum, the early Valentine made the case for these objects as examples of a “vanishing race,” and for a broader worldview in which the white race was meant to ascend (based on its “civilization,” rooted as it was in the classical heritage evinced in the plaster cast collection in the basement). Visitors, generally most likely white and middle-class (or above), would, in turn, have the shared belief in Euro-American exceptionalism that made this display and symbolism obvious, even in lieu of detailed labels.

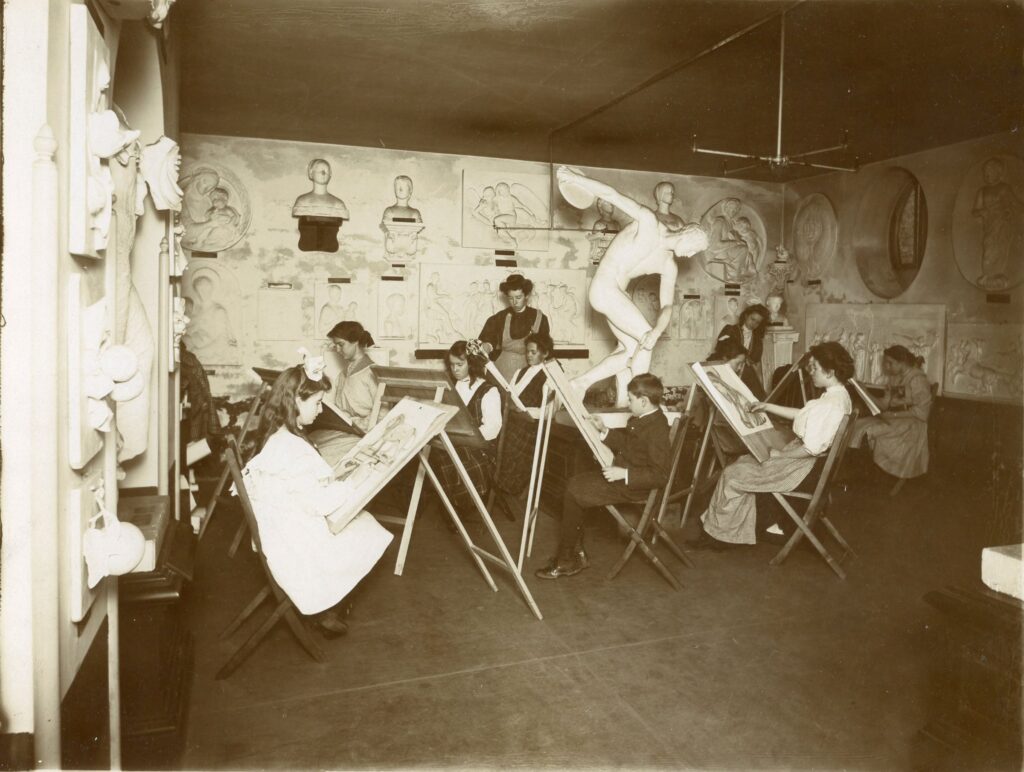

From the Department of Archaeology, visitors in the early 20th century traveled down to the basement to the Department of Sculpture. Granville G. Valentine, the eldest son of Mann S. Valentine II, acquired casts of sculptures from “the British Museum, the Vatican and elsewhere…from original marbles, bronzes, tablets, masks, etc., of Assyrian, Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Renaissance, and Modern times…” The United States had little in the way of sculpture with which to fill its new museums in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Presented in distinct contrast to the Indigenous collection, the sculptures represented “human art, under heavenly guidance,” and were collected to “encourage the study of Art” by “art teachers and students in Richmond.” The United States had little in the way of sculpture with which to fill its new museums in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, and a receipt in the Valentine Museum Archives proves that some of the casts in the Valentine Museum were purchased through D. Brucciani & Co., a well-known London firm.

Granville Valentine stated in his introduction to the cast catalog that he was “stimulated by the hope that this collection, and the catalog accompanying it, will give our people a higher appreciation of the beauties of plastic art, and perhaps encourage the development of talent in that direction amongst us.” This collection was made available to students, and, in 1903, the Board of the museum noted an increase in visitation of teachers and their students. By 1906, 78 were students enrolled in art classes at the Valentine hosted by Richmond’s Art Club.

In the early 1900s, Richmond was a deeply segregated city, but the Valentine Museum was open to both white and Black citizens of Richmond. In October 1902, the Valentine Board of Trustees approved welcoming all Richmond Public Schools students, but white and Black students were not allowed to visit on the same days until the 1960s and the end of segregation.

In the 1920s, Granville Valentine reached out to Laura Bragg (1881-1978), the director of the Charleston Museum in South Carolina. He did so as he felt that the museum was in need of a redesign to better reflect the current museum practice and philosophy of the early 20th century. Bragg had taken the helm of the Charleston Museum in 1920, making her the first female director of a publicly-funded museum in the country. A trained museum professional, she also considered herself a “social missionary,” believing that museums should be teaching tools rather than simple attractions for visitors. The museum had bought the row houses next to it between 1905 and 1928. The new plan moved much of the Valentine’s collection out of the Wickham House into the row houses and turned the Wickham House into a historic house with period rooms, similar to those installed in the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In a letter to Granville Valentine, Bragg told him: “You are going to make it as lovely for this day and generation as it was for its own when first installed.” In turn, Valentine stated: “It will be the greatest satisfaction to me if the Valentine Museum can ever be started along the lines for the good of the people generally. I hope someday we may get citizens interested in a City Museum.” With assistance from her protégé and companion, Helen McCormack (1903-1974), Bragg reorganized the Valentine Museum during a two-year closure.

Bragg arrived in Richmond in the summer of 1929 and the installation was finished in October of 1930. In the weeks leading up to the reopening, Granville Valentine suggested that the museum was not quite ready, but Bragg pressured him to move ahead, writing “A finished museum is a dead one.” After the opening, Bragg would go on to other projects while McCormack stayed on as director of the Valentine Museum until 1940.

“In the newer building the story of development is shown. You enter from the street, with its every evidence of the 20th century, into rooms where Virginia art of the nineteenth century is exhibited. As you go up to the second and third floors, if you turn consistently to the right, you will follow through room after room into a more and more distant past, until finally on the top floor you have reached the stone age exhibits, the very beginning of man. ”

While principles of design and museum philosophy may have changed, none of these new concepts challenged the perceived superiority of white western civilization.

Edward Valentine, the museum’s first President, died just two days before the official re-opening of the museum in October 1930. In March 1931, the museum opened two new installations in the ground floor of the row houses featuring Valentine’s Recumbent Lee plaster statue and his marble group, Andromache and Astyanax. The story of Edward Valentine and his role in developing visual imagery of the Lost Cause myth became more prominent after the City of Richmond relocated his studio to the Valentine campus in 1937. The Valentine Museum continued to expand in the 20th century and in the 1980s began exploring the history of inequity and racial oppression in Richmond.

Sources

- Note, September 26, 1848, Mann Valentine II Papers, The Valentine.

- Codicil to the will of Mann S. Valentine, October 17, 1892.

- “Valentine Museum Ready,” Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, VA), November 20, 1898; The Valentine Museum, Eleventh and Clay Streets (Richmond, VA), 1898.

- “Valentine Museum Ready,” Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, VA), November 20, 1898.

- Julie Schimmel, “Inventing the Indian,” in The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820-1920, edited by William Truettner (Washington and London: Published for the National Museum of American Art by the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991), 168.

- Gruber, “Ethnographic Salvage and the Shaping of Anthropology,” 1293.

- In 1989, the Valentine transferred the entirety of its known collection of Native American human remains to the Commonwealth of Virginia’s Department of Historic Resources in anticipation of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (1990) enacted by the U.S. Congress. Since that initial transfer, the Valentine has fully inventoried its remaining ethnographic holdings and continues to work with Indigenous tribes to repatriate additional materials.

- Trustees of the Valentine Museum, History of the Founding of the Museum (Richmond, VA: The Valentine Museum, 1915), catalog, 39-40.

- Trustees of the Valentine Museum, History of the Founding of the Museum (Richmond, VA: The Valentine Museum, 1915), catalog, 1.

- Stephen Dyson, “Cast Collecting in the United States,” in Plaster Casts: Making, Collecting and Displaying from Classical Antiquity to the Present, ed. by Rune Frederiksen and Eckhart Marchand (DeGruyter, Inc., 2010), 563.

- “Valentine Museum Ready,” Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, VA), November 20, 1898; Trustees of the Valentine Museum, History of the Founding of the Museum (Richmond, VA: The Valentine Museum, 1915), catalog, 90.

- Stephen Dyson, “Cast Collecting in the United States,” in Plaster Casts: Making, Collecting and Displaying from Classical Antiquity to the Present, ed. by Rune Frederiksen and Eckhart Marchand (DeGruyter, Inc., 2010), 563.

- Mary, M.P. Newton, ed., Description of the Casts in the Valentine Museum From Original Marbles and Bronzes (Richmond, VA, 1898), 1.

- Valentine Museum Board of Trustees Meeting Minutes, October 1902.

- Louise Anderson Allen, A Bluestocking in Charleston: The Life and Career of Laura Bragg (Colombia, SC: The University of South Carolina Press, 2001), 151.

- Jennifer McCormick, “Laura Bragg: Librarian, Educator and Director of The Charleston Museum,” last modified March 2020, https://www.charlestonmuseum.org/news-events/laura-bragg-librarian-educator-and-director-of-the-charleston-museum/.

- Bruce M. Stave, “A Conversation with Frank Jewell: Urban History at the Valentine Museum,” Journal of Urban History 18, no. 2 (1992): 197.

- Laura Bragg to Granville Valentine, n.d., Valentine Reorganization File, Valentine Museum.

- Granville Valentine to Laura Bragg, September 5, 1928, 1929–1930 Bragg Correspondence, Valentine Papers, Valentine Museum.

- It is clear from Helen’s correspondence how much she loved Laura, but less clear how deeply Laura felt about Helen, having lost her long-time partner Belle in 1926. Allen defines these relationships as “romantic friendships,” also called “Boston marriages,” whereby women could escape the traditional pressures and roles of heterosexual marriages but still find companionship and pool emotional, physical, and financial resources. To what extent Bragg’s relationships were also sexual is unclear, though it seems physical attraction and affection were a part of them. Allen, A Bluestocking in Charleston: The Life and Career of Laura Bragg, 47 and 111-112.

- Laura Bragg to Granville Valentine, September 13, 1930, Valentine Museum.

- Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 4, 1930, pg. 5; https://schistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/McCormack-Helen-G-papers-1069.00.pdf

- https://schistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/McCormack-Helen-G-papers-1069.00.pdf

- Helen Gardner McCormack, “The Valentine Museum and Its Function,” Virginia Journal of Education 27 (1934), 285.

- “Valentine Exhibit Opens Tonight,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 10, 1931, pg. 13.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Kate Sunderlin, Ph.D., Co-Curator of Sculpting History: Art, Power, and the “Lost Cause” American Myth |

|---|---|

| Work Title | The Early Valentine Museum, 1898–1930 |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | November 2, 2023 |

| Updated | May 24, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |