Voting Political Action Group: Richmond Forward

In 1972, Richmond suspended local elections for five years. It’s a long story…

By Valentine Museum Staff

From the Revolution to the Civil War to Reconstruction to Civil Rights, various seemingly impossible political situations have played out in Richmond.

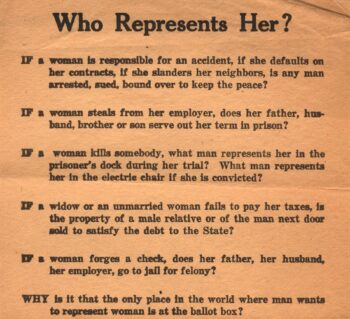

Before 1977, Richmond City Council members were elected at-large, meaning that in order to win, a candidate had to secure the most votes citywide. This political structure maintained neighborhood segregation and prevented Black districts from electing their own council members. But when the 1960 census revealed that Richmond’s population was 42% Black and would soon become the majority, it became clear that those wishing to maintain white political power had to update their tactics. Soon, various campaigns to maintain white control of the city took shape. The first attempt was a 1961 referendum to consolidate the city with Henrico County. Voters of both races turned it down.

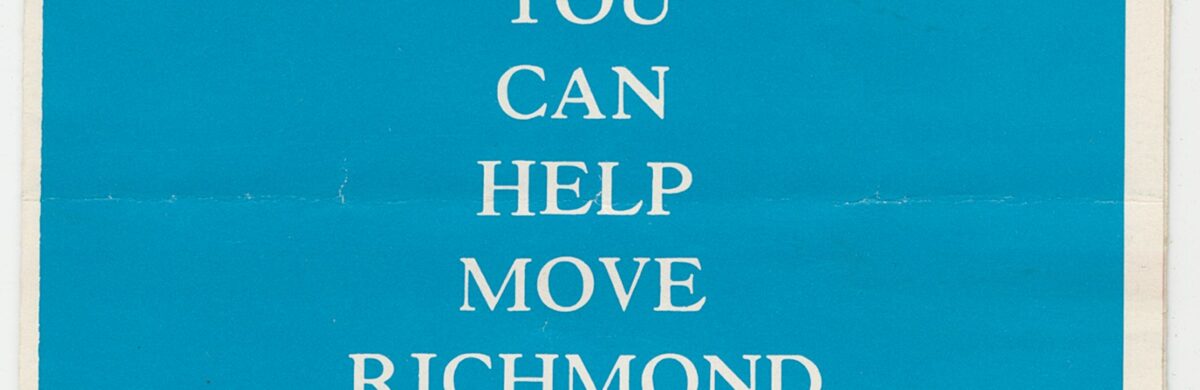

By 1963, the white power structure grew increasingly desperate. The city’s 1948 charter, which banned party affiliation for Council members, turned out to be one of their main obstacles. To work around this, powerful business leaders founded a political action group called Richmond Forward. Technically run by citizens, Richmond Forward behaved exactly like a political party. They picked candidates, funded their campaigns, and promoted them as a unified bloc.

During the 1964 election, they presented nine candidates to Richmond voters, who all shared a mission statement, a platform, campaign literature, campaign events, and the deep pockets of Richmond’s business elite. With the exception of former Council member Eleanor Sheppard, the Richmond Forward candidates had nearly no political experience. They largely came from real estate and banking.

Six of the nine Richmond Forward candidates won the at-large election, among them Eleanor Sheppard. In their first act as a majority, they elected two of their own as mayor and vice-mayor. Quickly, Richmond Forward got to work fulfilling their campaign promises to run Richmond in a “businesslike” way. They pledged to make sure that “all city officials take a positive, helpful attitude toward the legitimate needs of business.”

Richmond Forward was careful to never use racist language. They claimed “economic development” to be the goal of annexation and large public works projects. However, Richmond Forward’s critics—including remaining independent council members—noticed that most of Richmond Forward’s members and the owners of the businesses they supported lived outside city limits. Richmond Forward’s stated priorities of building more expressways, parking lots, the Coliseum and even a mall downtown would require the demolition of thousands of mostly Black-owned city homes, all in an effort to make Richmond more accessible to and profitable for white suburbanites.

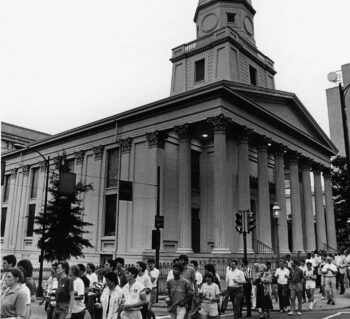

In the late 1960s, Richmond Forward literally cleared the way for the Downtown Expressway and expansions of I-95 and I-64. The historic Black neighborhood of Navy Hill was wiped off the map to build a connector between the two highways and the Coliseum. A thousand families were displaced, with some finally resettling in public housing.

By 1965, Richmond’s population outpaced predictions, with Black residents making up 52% of the population. That year, Richmond Forward revived efforts to annex parts of Henrico County. When the plan failed again, the group grew even more desperate. During the 1968 election, incumbent Richmond Forward councilman James Wheat, Jr. said blatantly that without annexation, “Richmond will become a permanent black ghetto.” In 1968 and 1969, the group poured its resources into promoting the ultimately successful annexation of 23 square miles of Chesterfield County, which took effect in 1970. Richmond suddenly gained 47,000 more residents, 97% of whom were white. Overnight, the city became 42% Black again.

Ironically, the 1970 annexation that was supposed to save Richmond’s white majority backfired. That same year, mandated busing became law. Almost immediately, the 47,000 new citizens of Richmond realized that they would now have to send their children to integrated schools. Thus, many white families fled to Chesterfield, dwindling the slim majority.

The annexation also prompted a Voting Rights Act lawsuit that reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which handed down an injunction, prohibiting Richmond from holding local elections until the case was decided. Richmond went from 1972 until 1977—five years— without local elections. In their eventual decision, the justices found Richmond’s at-large Council elections discriminatory.

The city was forced to switch to a ward system, in which separate districts each elect one council member. In 1977, the first first local elections held in five years, Black candidates won a majority on City Council for the first time in the city’s history. The Council then proceeded to elect Henry Marsh III as Richmond’s first Black mayor. Overnight, The majority of Richmonders had finally won majority representation.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | Voting Political Action Group: Richmond Forward |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | October 12, 2023 |

| Updated | May 24, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |