Belle Bryan Day Nursery and the Richmond Women’s Christian Association

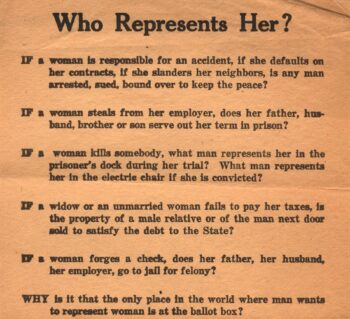

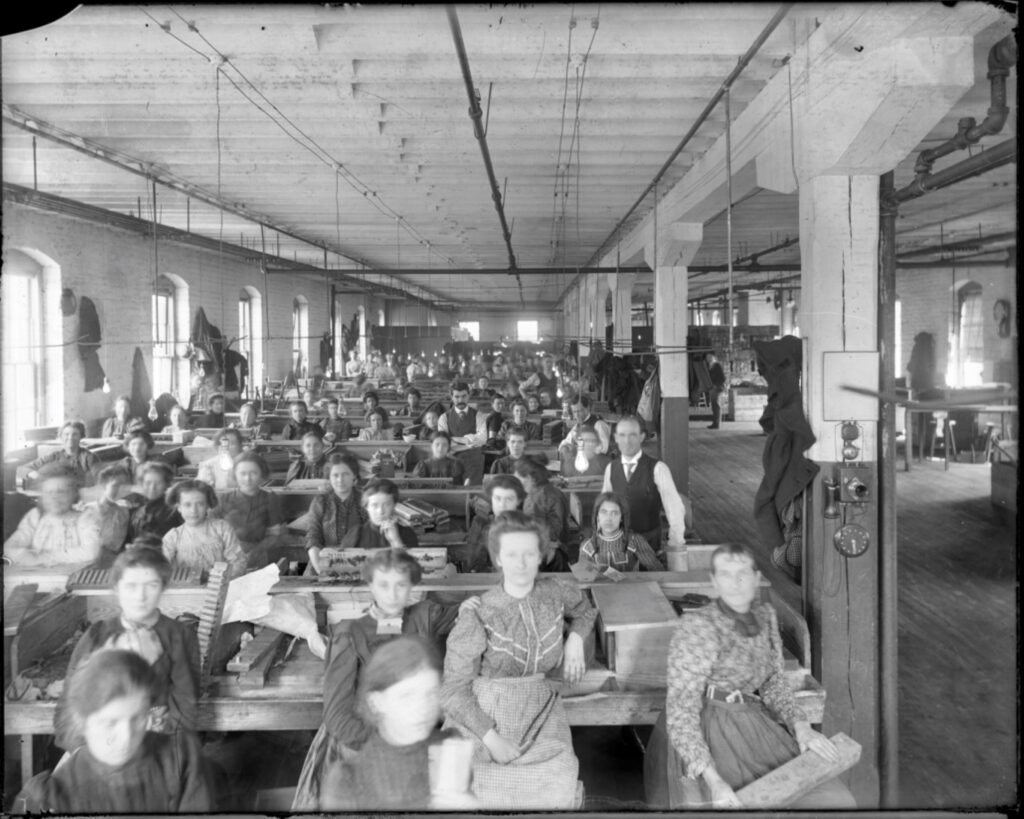

All mothers work. But the title of “working mother” is now associated with contemporary history, tied to women’s employment. But mothers have always worked outside the home, especially mothers from poor households. Here in Richmond, major industries thrived on the exploitation of largely women workforces, both Black and white.

By Valentine Museum Staff

Textile mills and some large operations within tobacco factories relied almost exclusively on women, who were paid very low wages to perform brutal jobs. Often, before child labor laws, children worked beside their mothers. If a child was too young to work, many factory-employed mothers left small children under poor supervision—sometimes by older children. Sometimes they had no choice but to leave their children unattended all day.

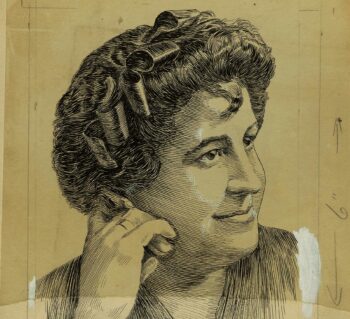

A Richmond woman named Isobel “Belle” Lamont Stewart Bryan was well-aware of the struggles of working mothers. In 1887, Bryan helped to found the Richmond Woman’s Christian Association (later the YWCA), which provided women factory workers with hard-to-find safe, clean and affordable housing. The RWCA also offered medical care, sewing classes, a library and religious instruction. As the daughter of a wealthy tobacco merchant, Belle Bryan did not have first-hand experience of economic hardship, so her concern for the plight of wage-earning women might seem surprising. She lived on a large estate on the North Side, called Brook Hill, and frequently traveled to Europe. And she undoubtedly had help raising her own six children. Perhaps her activism stemmed from what she witnessed at her father’s tobacco warehouse. Whatever the source, she quickly discerned that safe housing was not enough to help Richmond’s working women. In 1890, as chairman of the RWCA, she founded and chaired a free kindergarten and day nursery in the factory district for white children.

Belle Bryan Day Nursery opened at 6:30 a.m. and accepted babies as young as one month old. As the children arrived, they immediately received a bath and clean clothes. Their days included nourishing meals, nap time, play time, education and even medical exams by a nurse. For all this, mothers paid the small sum of 15 cents per week. And they could proceed to their long, exhausting workday with peace of mind, knowing that their children were safe and fed. The kindergarten was free. Of course, operating costs far exceeded 15 cents per week, per child, so Bryan became a tireless fundraiser. She received grants from City Council and larger charities, solicited churches and organized fundraisers to keep the charity afloat. Fancy dress balls at The Jefferson Hotel made charitable giving to the nursery a highly anticipated fashion event for Richmond’s elite families.

In 1898, the nursery moved to rented quarters 201 N. 19th Street, where it remained for 45 years. By the 1950s, the nursery moved to a larger rented space downtown and charged on a sliding scale, according to need: from ten cents to two dollars a day. In 1961, the nursery erected its own building at 610 N. 9th Street to accommodate the 75 children in its care.

A rapidly changing downtown, however, began to cut the nursery off from its mission. Urban renewal throughout the 1960s had pushed many poor residents out. “Slum clearance” programs, highway construction and newly constructed superblocks of government buildings and parking lots turned a bustling city center into a white-collar business district. Factories moved to isolated suburban locations. Citing these changes, the Belle Bryan Day Nursery ceased operations in 1971. The progressive charity had been ahead of its time for 80 years and it closed just as Women’s Liberation Movement began to take off and the term “working mother” took on a whole new meaning.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | Belle Bryan Day Nursery and the Richmond Women’s Christian Association |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | December 2, 2020 |

| Updated | May 28, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |