Essay: Racist Caricatures by Edward Valentine

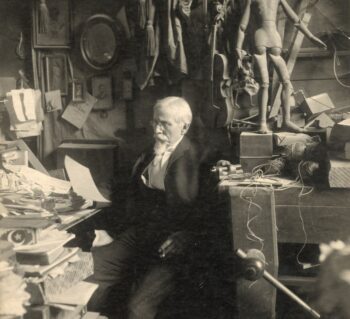

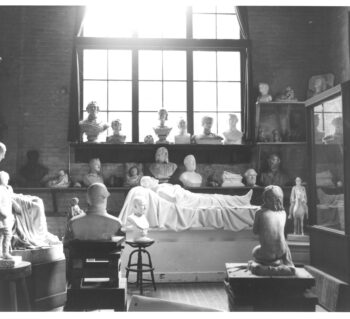

Edward Valentine (1838-1930) was a Richmond sculptor and brother of the founder of the Valentine Museum. Best known for his busts and statues of Confederate soldiers, his three sculptures of Black Richmonders are a disturbing subset of his work that express the explicit racism of the 1860s and 1870s.

By Kate Sunderlin

Ph.D., Co-Curator of Sculpting History: Art, Power, and the “Lost Cause” American Myth

These three works helped popularize demeaning visual stereotypes of African Americans that supported continued violence and oppression of Black Americans. Valentine created and cast in plaster The Nation’s Ward and Knowledge is Power in 1868, and he seemed to have conceived them as a satirical pair. Valentine started working on Uncle Henry, Ancien Régime in 1873 but did not cast it in plaster until 1879. These artworks, sold around the country for display in homes, are the visual opposites of Valentine’s Confederate statuary. Valentine was interested in presenting distorted “types” to his viewers, not realistic portraits of individuals. His intent, using satire and caricature, was to portray Black Americans as incapable of taking care of themselves, unworthy of an education, and better off enslaved. These sentiments, embedded in plaster sculptures, reinforced the false Lost Cause mythology that slavery was a beneficial social structure for both enslavers and enslaved person. Edward Valentine’s privileged status as an elite white male artist gave his sculptures an air of truthfulness that white viewers seldom questioned. All three works reveal not only Valentine’s own personal racist sentiments, but also the pervasive racism and bigotry of the era, evidenced in the sculptural narrative and formal qualities of each piece.

The Nation’s Ward

The half-length bust of The Nation’s Ward depicts an African American boy, who looks to be between the ages of eight and twelve years old. Valentine used stereotypical features to identify this figure as a person of Black African descent such a broad nose, full smiling lips, and exposed teeth. Much of the figure’s head is covered by the cap he wears, which evokes the kepi, or forage cap, part of a Civil War military uniform worn by units in the North as well as several Confederate units. He gazes upward, either towards heaven or towards an unseen figure, perhaps in gratitude or adoration. His shirt is tattered and ill fitting, a bit too big for the boy wearing it. A strap across his chest suggests he would have been carrying something, most likely a bag.

Valentine modeled The Nation’s Ward after a Black boy that came to the door of Valentine’s studio looking for work, specifically asking to put the coal away.

Instead, Valentine brought him inside to model for him (there is no mention of whether or not Valentine paid him for this service). In a photo of the young boy that Valentine kept in his files, he is shown posed outside in the center of the street gazing to the photographer’s right, mouth slightly open, possibly mid-speech. He wears a jacket, shirt, trousers, boots, and cap. The clothing of both figures in Knowledge is Power and The Nation’s Ward are reminiscent of this boy’s actual clothing, but the fact that the boy’s clothing is not an exact match reveals two things. First, Valentine no doubt had a more specific costume in mind for The Nation’s Ward and meant to evoke wartime clothing and give the impression of abject poverty. Second, by altering the boy’s clothing to suit his artistic vision, Valentine is more concerned with portraying a type of person more than creating an actual portrait. Just as the boy’s clothing is not an exact match between the photograph and Valentine’s portrayal, neither is the portrait. The model seems to have a rounder face and slightly smaller frame than the figure of The Nation’s Ward. Perhaps this discrepancy means that Valentine used the model more for preliminary studies and that the model’s identity was not considered particularly important. The model’s inconsequence is further confirmed as his name was not recorded on the photograph or included in the title of the work. Again, the end result was meant to represent a caricature not an actual person.

Valentine executed this work very quickly, commencing his sketch on January 3, 1868, when the boy first came to him, and having it cast on January 24, 1868. It was not until March 3, 1868, that Valentine inscribed the words “The Nation’s Ward” on the work. On May 13, two women reportedly visiting from the North viewed the work and one “said what a pretty name and sentiment it was, but on conversing with a Southern gentleman found it was meant as a satire.”

During and after the Civil War, the nation debated what was to be done with the recently freed and soon-to-be freed enslaved persons populating the South. After the Civil War, recently freed Black Richmonders faced a difficult situation. With little to no money or property to their name, and generally little to no education, how they were to provide for themselves as well as any family members was tenuous at best. Republicans, especially Radical Republicans, were the most outspoken advocates of the freedmen, trying to advance legislation that would secure them education, enfranchisement, and aid. But many white citizens were uncomfortable with and downright hostile to such developments. In August of 1867 as Black and white Virginians gathered in Richmond to discuss a new state constitution, Valentine wrote to his brother William: “About the only excitement we have here now is Hunnicutt’s Convention. The n*****s were assembled today on the Square, but nothing was done or said that is going to shake the world. The n*****s day will pass before many years.” Valentine’s crude language and disdain for Black Virginians is carried through into his portrayal of the young Black boy who showed up to work for him the following winter.

Valentine’s figures point only in one direction, towards racial caricature, particularly The Nation’s Ward. In her biography of her uncle, written with assistance from his diaries, Elizabeth Gray Valentine states that the young boy depicted is “charming and characteristic of “the pickaninny.” While this sculpture may have been perceived as satire at the time, it is now clear that this work is an example of a racist caricature, the picaninny, extremely popular at the time and for most of this country’s history. Advertisers and publishers often used the stylized imagery on postcards, posters, illustrations, and other ephemera, including advertisements.

By drawing upon the character of the picaninny, Valentine is reinforcing the stereotype of African Americans as lazy, often portrayed in cartoons of the era as comical in their indolence and ignorance. He seems to be making a cruel joke at their expense, masked as “good humor,” ridiculing what he and others perceived as their misguided reliance on the Federal government and their lack of the Anglo-American work ethic.

Plaster caricatures like Valentine’s would be displayed in homes where they might be viewed in relation to such advertisements in the newspaper placed on the table next to the statue perhaps, and racist home goods items, like ”Mammy” sugar bowl set on a kitchen table. These visual relationships highlight the ubiquity of racism, spanning from kitchen tables to government policy. It also speaks to how that universal visual backdrop affects Americans, particularly white Americans, to view people of color a certain way, which paves the way for imbalanced and racist policy-making.

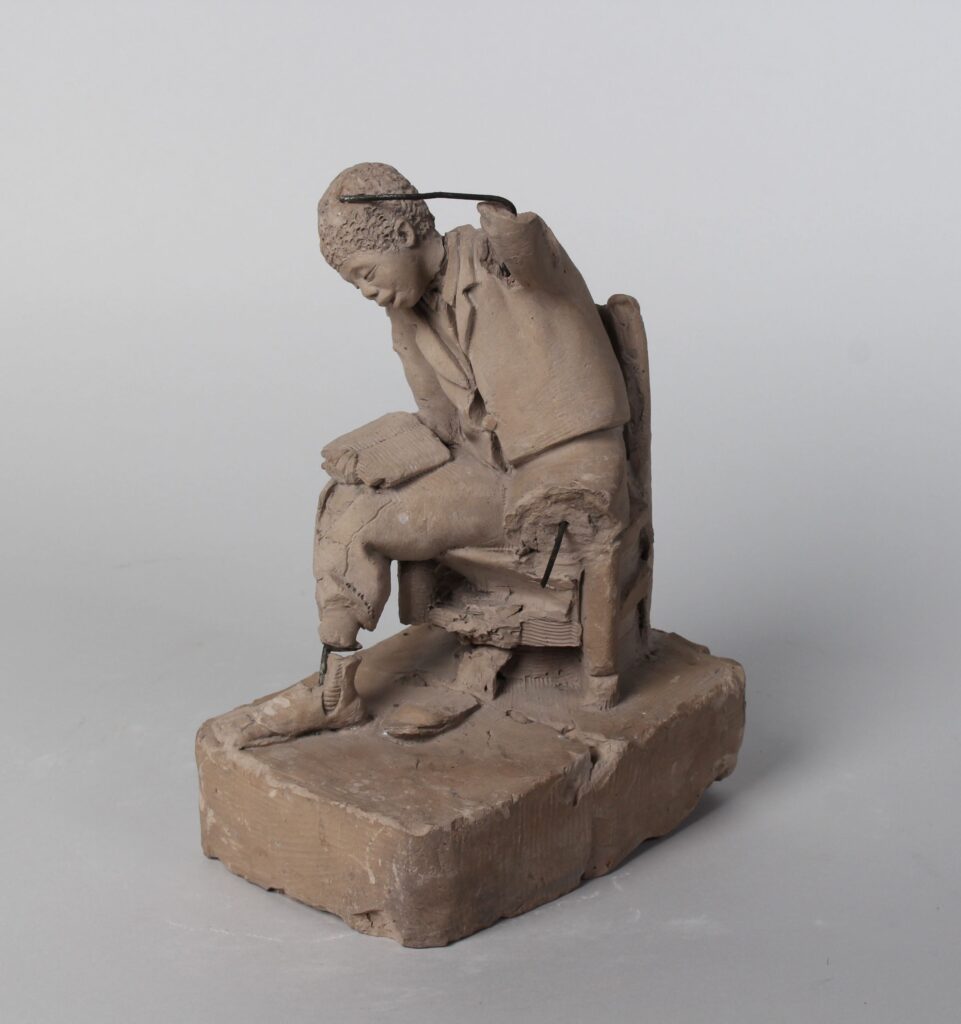

Knowledge is Power

Knowledge is Power depicts another African American boy, about the same age as the boy depicted in The Nation’s Ward. Valentine also exhibited him with the stereotypical facial features associated with African Americans and wearing patched clothing. His jacket seems too small, the cuff riding far above his wrist. His shoes are mismatched, one of them is even missing part of its leather, leaving the boy’s toes exposed. One of his pants’ legs is patched at the knee, the other has a hole in need of patching. He sits on a chair covered with a quilt or blanket, and he is slumped over, as if he has only just fallen asleep. Indeed, his fingers still grasp the book in his hand. Given the title, it is assumed that this would be a schoolbook of some sort.

Conceived and cast in January and February of 1868, alongside The Nation’s Ward, Knowledge is Power is undoubtedly related to the contested development of the public school system in Richmond and makes an argument against or mockery of Black education. Public education in Richmond was in its infancy following the end of the Civil War. Prior to the Civil War, white families who had the money could hire tutors or send their children to private schools, like the Valentine family. Within weeks of the Union victory, Black churches in Richmond opened schools. On May 9, 1865, the Anglo-American newspaper noted “the schools will be opened at 9 o’clock this morning in all the colored churches of the city.” The Freedmen’s Bureau and Northern missionary groups bolstered these schools and opened others.

In 1869, Richmond established its own segregated public school system in the same year that the newly-adopted state constitution created of a segregated statewide public school system. Richmond’s African American delegates to the Constitutional Convention protested this separation, arguing that it set a dangerous precedent. However with dwindling northern aid to African American schools and the closure of the Freedmen’s Bureau’s operations in 1870, Richmond’s African American citizens focused their concentration on the survival of their existing schools over integration of the two systems. The school remained segregated because white politicians believed that to put both races in the same classroom would result in a white boycott and thus the collapse of the entire school system.

The posture of the Black schoolboy in Knowledge is Power represents a conscious choice on the part of Edward Valentine and reveals the deep-seated prejudices and fears of an elite, white audience. In an earlier clay model, the young boy is shown with his arm raised, thus actively participating in his education. In the final version, Valentine sculpted him slumped over asleep on a carpet-covered stool. Valentine wrote in his diary on January 31, 1868, that he had begun work “in clay for the “student” a figure of a little negro that I wish to model.” But on February 20, he noted his foundation work for the “large sleeping negro.” Valentine also considered other titles for the work like The Little Truant, A Scholar at Sleep, and Learning Under Difficulties. Choosing the widely-used maxim, Knowledge is Power, and showing the young boy asleep with his schoolbook open on his knee, Valentine is implying that African Americans are not suited to the rigors of learning. This is in stark contrast to the clamor for education in Richmond in the years after the Civil War. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper depicted a packed Freedmen’s Bureau classroom in Richmond in November 1866, with Black boys and girls reading from books.

Knowledge is Power was also described as a bit of “humor,” but is perhaps more accurately interpreted as Valentine’s racist commentary on the subject of education for African Americans. A reporter discussing both Knowledge is Power and The Nation’s Ward in the Daily Patriot from Washington, D.C. also picked up on the “humor” in these sculptures, describing both as “very amusing works by Valentine…[that] delineate most aptly the two conditions of happiness most appreciated by the negro;” those conditions seemingly being ignorance and laziness in the view of this reporter. Virginian John Esten Cooke (1830-1886) in a letter to Valentine states, “You display in this figure a trait which I knew you to possess, socially and personally, but did not know you possessed artistically! I mean humour and the perception of the ludicrous.” Obviously this acquaintance, like Valentine, found the idea of Black education ludicrous. Cooke continues to discuss how Valentine developed “Africanism” beyond what others had and that the figure served as one of the attractions of his center table the previous evening during a social gathering at The Briars in Clarke County, Virginia.

Conceived as a pair, customers from around the country purchased plaster versions of both The Nation’s Ward and Knowledge is Power for $22 or $24, respectively. Valentine retailed them through Tiffany & Co. in New York and also sold them privately to Cleveland, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and San Francisco in addition to local Richmond clients like T. C. Williams.

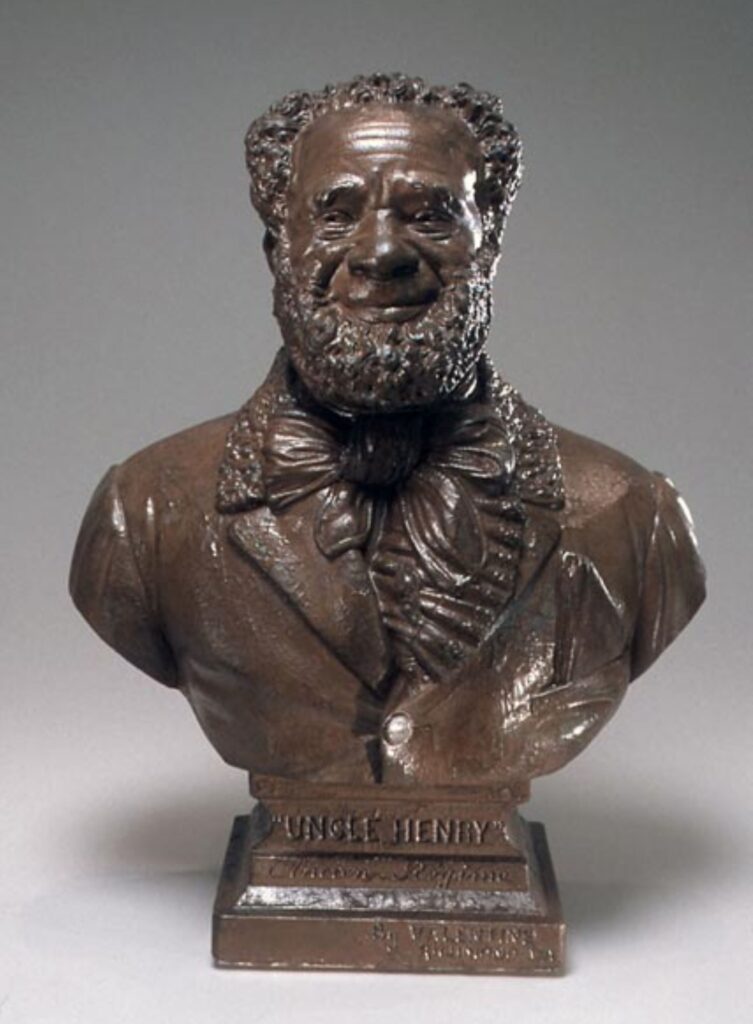

Uncle Henry, Ancien Régime

The final work Valentine completed depicting an African American is titled Uncle Henry, Ancien Régime. In contrast to the two young boys, Uncle Henry seems to be relatively well dressed, perhaps in servant’s livery. Henry Page (d. 1886) served as the model for the bust in 1873. The Valentine family had enslaved him as a carriage driver prior to the Civil War and Emancipation. It is not surprising Edward Valentine would depict him this way, particularly given southern whites’ postwar nostalgia for the Antebellum era. Again, Valentine has relied on stereotypical features to denote his race. That he is balding and has lines on his forehead and underneath his eyes implies he is older, perhaps middle-aged. He gazes straight out at the viewer, shoulders-squared, back straight, seemingly standing tall and proud. He smiles kindly, almost affectionately at us. Like The Nation’s Ward, the title of this sculpture is carved into the base. Its subtitle, Ancien Régime, in combination with the figure’s clothing and expression, are meant to evoke the trope of the faithful servant or “good slave,” the enslaved person that looks upon his master (or former master) with fondness and unswerving devotion. With this caricature, Valentine is offering one more visual point in his artistic post-Civil War social agenda of Southern redemption. Indeed, a reporter describing the statue in 1873 describes it as representing the “grandsire of the olden time” and contrasts it with The Nation’s Ward, which represents the “negro boy of the present day.”

Elizabeth Gray Valentine’s 1929 description of this bust is telling: “Many years later his “young master” modeled a bust of the old time darky with a broad grin and half closed merry eyes which express his adoration. He wears his coachman livery, soft stock with flowing bow over a ruffled front shirt.” He was described by Valentine himself in a letter as an exemplar of the “woolly aristocracy” and by a reporter in a local newspaper as a “colored aristocrat.” Like Elizabeth Gray Valentine’s description of Henry Page as an “old time darky,” these descriptors are meant to evoke the antebellum South, an era in that region’s history that had become laden with present southerners’ nostalgia for a perceived chivalric society where slave and master knew their place and existed in benevolent harmony. Newspaper articles discussing Valentine’s bust Uncle Henry and Henry Page himself, a supposed centenarian who could recall the “glorious” days before the war, constantly distinguish both his person and the type of enslaved person he represented from the freed people of the postwar era, both in his mannerisms and his dress.

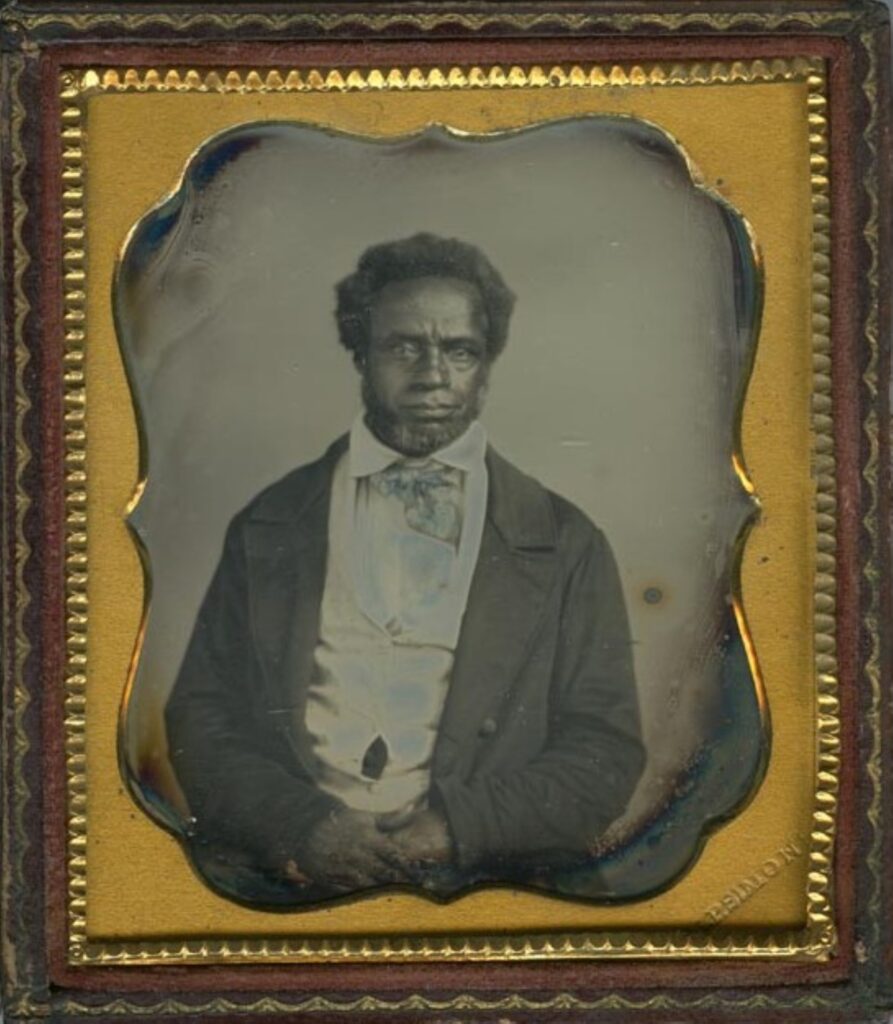

A daguerreotype taken of Henry Page by the Valentine family while he was still enslaved in the 1850s portrays a different attitude. Instead of broadly smiling, Page holds his face with straight lips and a pinched brow. His stock is askew, his vest is unbuttoned, and his coat is wrinkled. Although younger than the plaster portrayal, the photographed Page appears haggard and overworked, as if he has recently stepped inside from his role as a carriage driver.

A letter in the Valentine papers also provides additional insight into Henry Page, the man, not the caricature. Although written in the handwriting of Edward Valentine’s sister, Sarah Bennetta Valentine, the 1856 letter is from Page to his son living in another state. He opens with “Imagine the joy of a Father’s heart on receiving a letter from a son whom he had never expected to hear from again,” and then goes on to convey news of their family members and fatherly advice. He urges his son to “write soon and tell me all the news.” His focus on family relationships – including births and marriages – reveals that Page has a deep kinship network in the Richmond area. He also sends greetings from Richmond friends who have children that are living near his son and requests that his son send back information about them in a return letter.

These familial networks of enslaved people were often coopted by white owners, and after Emancipation were often remembered as friendlier or deeper than they had been in reality. Valentine’s title for his sculpture, Uncle Henry, Ancien Régime, could be evidence enough. The use of the title “uncle” “epitomize[s] the sense of affection that the “New South” believed – or wanted to believe – had existed in the “Old South” master-slave relationship…” This was a practice Southern whites borrowed from their slaves, who, forbidden to call older slaves by honorifics such as “Mr.,” “Mrs.,” or “Sir,” were taught by their parents to use the terms “Aunt” or “Uncle” as a sign of respect for older African Americans, whether or not they were relatives. While southern whites borrowed these terms to display affection for enslaved persons in their service, enslavers also used these titles to keep social distance between themselves and their enslaved workers. Furthermore, the “ancien régime” was a label for the hereditary monarchy and feudalism upheld by the European nobility Valentine’s reference to the old order belies his adherence to the Lost Cause and its sanitized view of the antebellum South that would be used to shape the historical discourse on the war and slavery in the succeeding decades.

Uncle Henry (in title and image) evokes one of the most famous characters in American literature, Uncle Tom, from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s sentimental novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or Life among the Lowly, published in 1852. The depiction of Uncle Tom in illustrations for the text, as well as prints and paintings, evolved over time, Originally, Stowe portrayed Tom as in the prime of his life and there were few other images in print of proud, able-bodied adult Black men in print and art But postwar and post-emancipation, this image disappeared.

Conclusion

Valentine’s caricatures as a whole are also part of the trend to avoid depictions of African American men as proud and able-bodied. Indeed, as his subjects are either young or old, Valentine completely avoided representing an African American man in his prime, which may have threatened white audiences, even if the threat was only perceived and not actual. With these distorted figures, he helped perpetuate one of the myths of the Lost Cause that painted the era of enslavement as beneficial not just for white enslavers but also for enslaved Black Americans. In bolstering this ideology, Valentine helped white Americans ignore the substantial gains of the post-Civil War era for Black Americans by dehumanizing them and visually trapping Black men in the stereotypes of needy childhood or elderly dependents.

Sources

- Charity S. Calvin, “Civil War Uniforms,” in Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe, vol. 2, eds. José F. Blanco et. al. (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2016).

- Elizabeth Gray Valentine, Dawn to Twilight (Richmond, VA: William Byrd Press, Inc., 1929).

- Letter to William Winston Valentine from his brother Edward Virginia Valentine, August 1st, 1867, Edward Valentine Papers, The Valentine Museum.

- David Pilgrim, “The Picaninny Caricature,” Jim Crow Museum, last modified 2023, https://ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/antiblack/picaninny/homepage.htm

- Logan Jaffe, “Confronting My Racist Object,” New York Times (New York, NY), Oct. 7, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/07/us/confronting-my-racist-object.html.

- Marianne Julienne & Brent Tarter, “The Establishment of the Public School System in Virginia, “Encyclopedia Virginia, December 20, 2020, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/public-school-system-in-virginia-establishment-of-the.

- Anglo-American, May 9, 1865, quoted in Hilary Green, Educational Reconstruction: African American Schools in the Urban South, 1865-1900. 2016, pg. 16.

- Marie Tyler-McGraw, At the Falls, Richmond, Virginia & Its People (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1984).

- Recollections Manuscripts Box 9, Folder 1866-1869, Edward Valentine Papers, The Valentine Museum.

- Daily Patriot (Washington, D.C.), September 23, 1872.

- Correspondence from John Esten Cooke to Edward Valentine, February 20, 1872, Edward V. Valentine Files, MS. C 57, Box 1, Valentine Museum Archives, Richmond, VA.

- Rachel Stephens, “Whatever is un-Virginian is Wrong!’: The Loyal Slave Trope in Civil War Richmond and the Origins of the Lost Cause,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no 1 (2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.9812.

- “Uncle Henry,” The Richmond Enquirer (Richmond, VA), December 7, 1873.

- Correspondence from Edward Valentine to unknown recipient, after 1881, MS. C 57, Box 32, Folder Clippings, Valentine Museum Archives, Richmond, VA.

- One Henry Page’s obituaries claimed he was 101 years old at the time of his death (The State, December 13, 1886). But the 1886 Death Register denotes him as being 86 years old when he died (Richmond, Virginia Death Register, 1886, accessed on Ancestry.com).

- Henry Page to his son, November 20, 1856, Mann S. Valentine Papers, Personal Papers, Box 1, Folder Servant Letters; Why this letter remains in the Valentine family papers is unclear.

- Kenneth W. Goings, Mammy and Uncle Mose: Black Collectibles and American Stereotyping (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1994).

- Ambrogio A. Caiani, “Re-inventing the Ancien Régime in Post-Napoleonic Europe,” European History Quarterly 47, no. 3 (2017), 438.

- Morgan, Uncle Tom’s Cabin as Visual Culture (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2016), 55.

- Charmaine A. Nelson, The Color of Stone (University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 129.

- Thomas A. Foster, Rethinking Rufus: Sexual Violations of Enslaved Men (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2019), 30.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Kate Sunderlin, Ph.D., Co-Curator of Sculpting History: Art, Power, and the “Lost Cause” American Myth |

|---|---|

| Work Title | Essay: Racist Caricatures by Edward Valentine |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | November 13, 2023 |

| Updated | May 24, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |