Knights of Labor

A new labor model was needed to address the changing economic landscape. That model could be found in the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor. Founded in 1869, it slowly evolved and expanded its mission and leadership so that by 1879, it was poised to harness the rising frustrations of the working class.

By Valentine Museum Staff

In 1882 and 1883, a nationwide economic slump led to layoffs across the country. Many of these layoffs became permanent, even as the economy recovered due to industries replacing more and more workers with machinery. Against this mass industrialization, traditional small craft unions found few victories. In Richmond, like in most American cities, small craft unions were nothing new. Organized by trade, however, they were limited in size and thus limited in power. There were only so many quarry workers or so many foundry workers in a single city. Many felt powerless against the mass scale of industrialization.

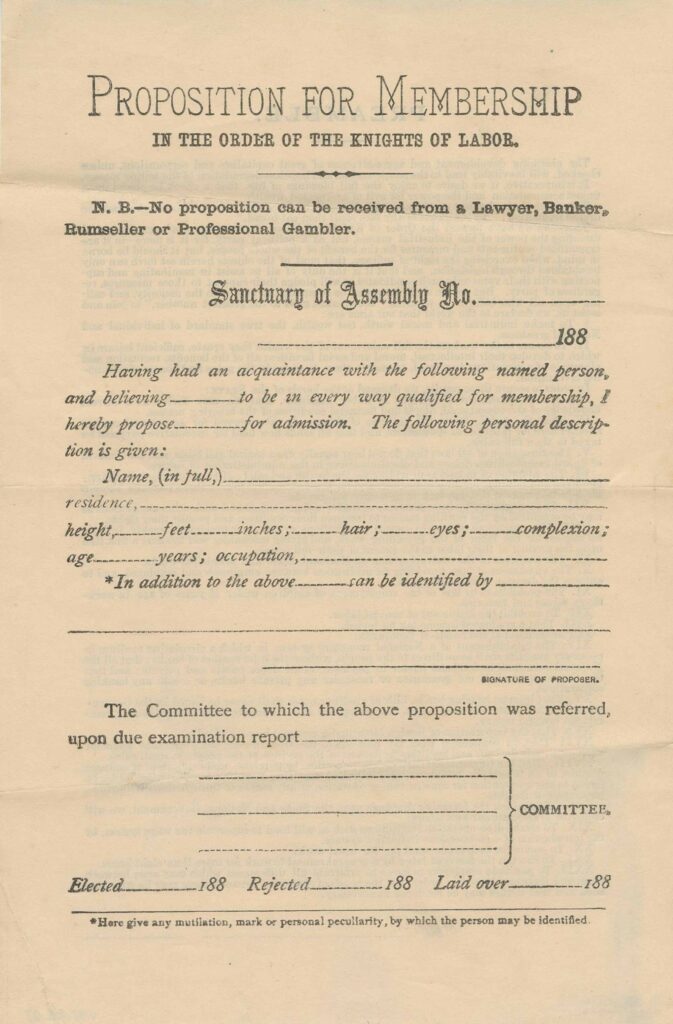

This union revolutionized the labor movement by inducting members regardless of trade. Anyone could join: iron workers, typographers, cigar makers, granite cutters, mill workers, barbers, builders, textile workers. With sheer numbers, the Knights could match the power of what they called “the great capitalists.”

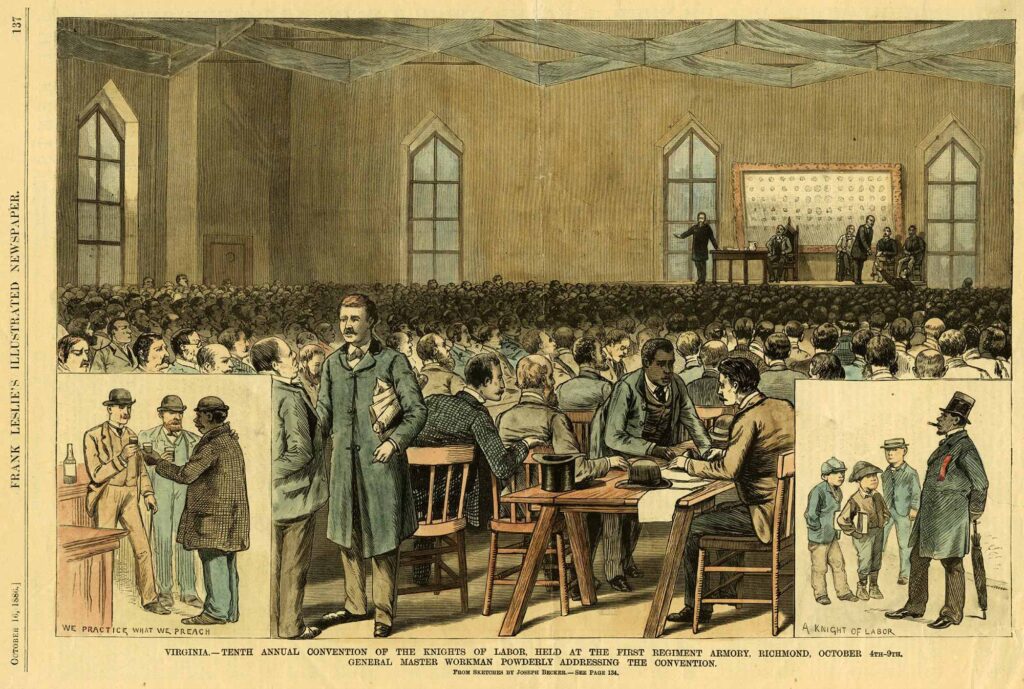

In April of 1884, the Knights of Labor spread to Richmond. Eleven white workers established “The Eureka Assembly.” At first, they struggled to gain more members. Corporate interests were strong and leaders exploited racial tensions within the working class to maintain power. But by the fall of 1884, Black workers had formed a few of their own assemblies. They could not be official Knights, however, without a charter, which they needed from the local white organizer. By that time, eight white assemblies had been established in the city. Fierce debate between them ensued. Some members were in favor of integrating the union, while some opposed the idea. The organizer, Charles Miller, wrote to the national office outlining the dilemma. Terence Powderly, the General Master Workman of the Knights, and possibly the most famous labor activist in the country at the time, did not reply to the letter. Instead, he came to Richmond.

He arrived in late January of 1885 and stayed for two days. In those two days, he held two meetings. In the first, open only to white members, he discussed the inclusive structure needed to not just address larger local issues, but to apply political pressure and to secure victories for workers. Powderly told the group:

“We organize the colored workers into separate assemblies, working under the same laws and enjoying the same privileges as their white brethren… The politicians have kept the white and black men of the South apart, while crushing both. Our aim shall be to educate both and elevate them by bringing them together.”

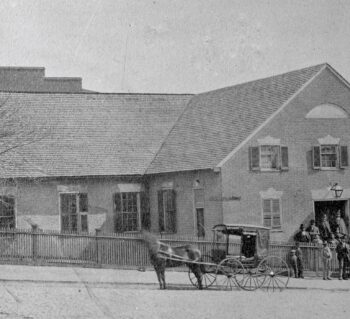

The next evening, he presided over a much larger meeting at the Old First Market Hall, at 17th and Main Streets. This meeting was open to everyone: Black and white, men and women, members and non-members. It was packed. There, he announced this separate but equal structure, quite radical for the time in Richmond. Never before here had Black and white workers belonged to the same union. The enthusiasm of the crowd was so great, Powderly later recalled that “I organized an assembly of colored men at the conclusion of the meeting.” After Powderly’s visit, membership to the Knights of Labor exploded in Richmond. Even the women were inspired to organize for the first time in this city’s history, forming an assembly of white women cigarette makers.

By retaining maximum flexibility for both membership and regional prejudices, the Knights of Labor drew in the numbers needed to fight rising corporate power. Of course, because of this flexibility, many things did not change for Black workers in their segregated assemblies and more serious divisions persisted. But Black and white workers did, for the first time in Richmond, exert political pressure as one. As membership boomed, the Knights held boycotts against offending businesses. One of their first actions as an “integrated” union was to take up the cause of Richmond’s coopers—a trade unique at the time for not being dominated by one race. Forced to compete with free convict labor, Black and white coopers struggled to make a living. In the summer of 1885, the Knights declared a boycott on the Haxall-Crenshaw flour mill in defense of the coopers, which bought convict-made barrels. Right away, they took on one of the biggest and oldest businesses in Richmond. By the end of the year, the Knights won. With that, thousands of white Richmonders were compelled to, and did, join a boycott that benefited poor Black workers—a feat nearly unimaginable in 1880s Richmond.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | Knights of Labor |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | September 4, 2020 |

| Updated | May 28, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |