Mary Munford: Richmond History Maker

Mary Munford once wrote to a friend: “Education has been my deepest interest from my girlhood, beginning with an almost passionate desire for the best in education for myself, which was denied because it was not the custom for girls in my class to receive a college education at that time. This interest has grown with my growth and strengthened with each succeeding year in my life.”

By Valentine Museum Staff

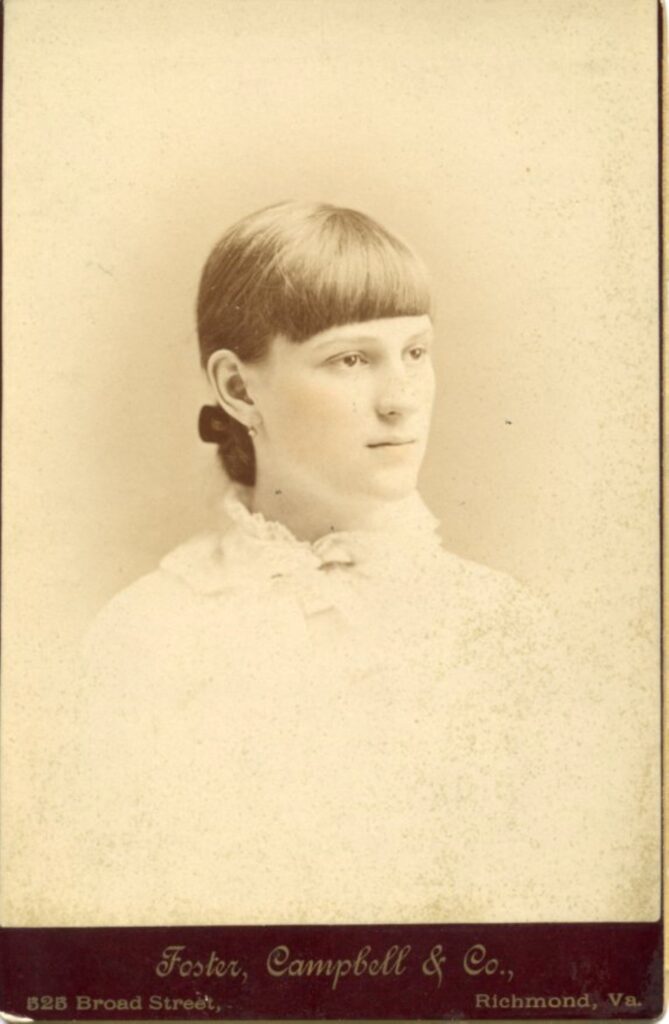

Around the time this picture was taken of Mary-Cooke Branch (1865-1938) in 1882, she was pleading with her mother to attend college. Though her Richmond family was prominent and wealthy enough to afford tuition, her mother refused. Her mother agreed with public opinion that the education of women was not only unnecessary, but downright scandalous. And so, Mary went to a finishing school instead—the common fate of most wealthy daughters at the time. Finishing school taught social graces and etiquette. Academic studies there largely aimed to make women interesting conversationalists for prospective husbands.

Undeterred, in the 1890s, Branch founded a women’s discussion group to harness the resources, influence and energies of other Richmond socialites for the greater good. But her efforts to talk about Jackson Ward’s sewage and hookworm problem over tea did not appeal to most members. The meetings inevitably devolved into finishing school-style conversations about poetry. Clever as she was, Branch did put her “husbandry degree” to good use. By 1893, she had attracted Beverly Bland Munford, a local lawyer and state legislator with a reputation for social activism. In this marriage, Mary Cooke-Branch Munford was much more than a conversationalist. She was a co-conspirator.

The couple would combine their talents and wills to fight educational discrimination by sex, race and class in Virginia and throughout the South.

In 1901, the Munfords and four other women founded the Richmond Education Association. The group raised awareness for the need for public schools for both Black and white children. Child labor was still the norm and, at the time, the state’s public education system was so sparse and underfunded that it was inaccessible to most Virginians. Wanting to expand her activism beyond Richmond’s borders, Munford also became president of the Cooperative Education Association, which sought to expand public education in rural areas. She traveled through the South as part of an interracial coalition to lobby governments and provoke citizens to demand more for their children. She co-founded the Virginia Industrial School for Colored Girls and served on its board of trustees. With these efforts, Munford helped to build new rural high schools, improve teacher training and establish agricultural and industrial schools in areas that had severely lacked in formal education.

When Munford’s husband died in 1910, she shifted her tactics from stoking public support for educational progress to provoking Virginia legislators directly. She likely learned a great deal about how power works from Beverly, who had served as both a state senator and a state delegate. At this time, Virginia funded four colleges to educate men, though none for women. Any woman with academic aspirations who wanted to further her education went to one the state normal schools, to be trained as teachers. Normal schools lacked accreditation and ranked far below college standards.

No doubt Munford had her own college dreams in mind when she created the Co-ordinate College League. The sole mission of this body was to lobby the General Assembly to build a sister college for women at the University of Virginia. Shrewdly, she argued that improving women’s education would improve men’s education as well, since most teachers of boys were, in fact, women. Despite opposition from lawmakers and the school itself, she mustered significant public support and incessantly revived the issue before the General Assembly. All efforts—in 1910, 1912, 1914, 1916, and 1918—failed. In 1916, the measure failed by only two votes. Her persistence finally paid off when the legislators caved and agreed to admit women to William and Mary in 1918. Two years later, the college appointed Munford as the first woman on their Board of Visitors. She would also serve as a trustee of the Black college, Fisk University. UVA granted her a place on their Board of Visitors in 1926, though the school would not admit women as undergraduates until 1970.

In 1920, Munford became the first woman to serve on Richmond’s School Board. Mary Munford Elementary was named after her in 1951, 13 years after her death. And though her most lasting impact remains on Virginia’s educational system, Munford’s activism was multi-faceted. From suffrage to labor to race relations, she fought for improved equality—although, notably, she never targeted segregation itself. She held office or influential appointments in several other progressive organizations throughout her life, including the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia, the YWCA, the National Child Labor Committee, the National Urban League, the regional Commission on Interracial Cooperation, the Virginia Inter-Racial Committee and many others. All this, she accomplished without a formal education and with two children. But if her finishing school education has taught us one thing it is that a woman cannot be finished—if she doesn’t want to be.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | Mary Munford: Richmond History Maker |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | March 5, 2021 |

| Updated | May 28, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |