James Monroe and the “Era of Good Feelings”

Monroe, in his 1817 inaugural address, declared that “discord does not belong in our system.” He then claimed that his main goal as president would be to foster “harmony among Americans.” He believed this harmony depended on the extinction of all political parties.

By Valentine Museum Staff

Our nation has nearly always been deeply divided in two, despite the warnings of George Washington himself, who loathed political parties. There was, however, a time our nation’s history when there were no political parties. Or, more accurately, there was but one party because the other party had spectacularly imploded. After the close of the War of 1812, that’s exactly what happened to the Federalist Party. Without their sworn foes to battle, the Democratic-Republicans were given the keys to the nation.

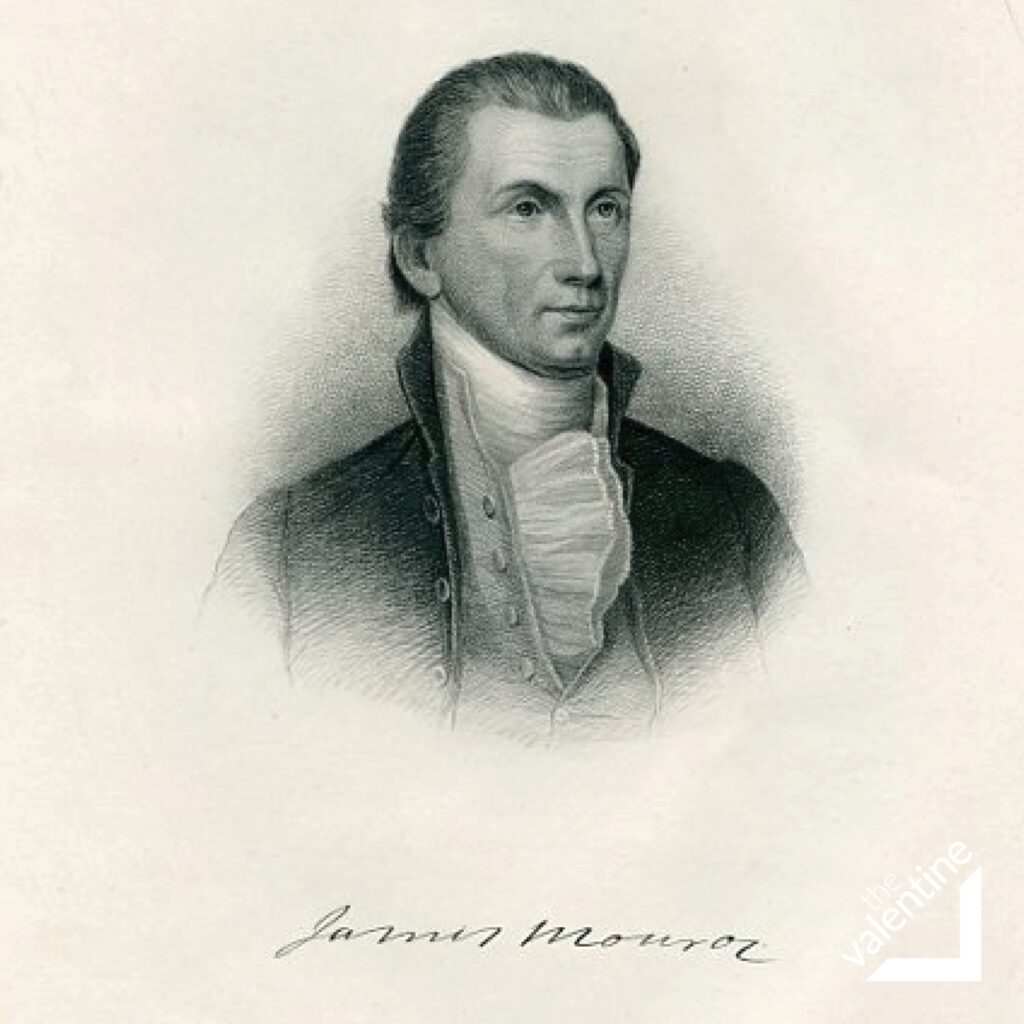

This curious time coincided with the two terms of President James Monroe, a Virginian who won the presidency in a landslide.

Monroe began his term with a goodwill tour of the country, spreading the message of unity and cooperation. Perhaps after decades of ugly partisanship and the War of 1812, for which Monroe had negotiated peace, the nation was simply too tired for more conflict. Whatever the reason, he was a hit nearly everywhere. Even in Boston, the Federalist citadel, he was greeted by thousands of rose-waving children, dressed in white. Once-powerful Federalist leaders who would not have stepped into the same room with Monroe before attended the banquet in his honor. The Columbian Centinel, a staunch Federalist newspaper, ran the headline that would come to define the Monroe Presidency: “Era of Good Feelings.”

Of course, it’s easy to feel good once your side has triumphed over all opposition. And even easier to call a system in which your party rules unopposed a “partyless” utopia. Monroe had himself been involved in violent partisanship that nearly brought him and Alexander Hamilton (Federalist Foe #1) to a duel in 1797. But Monroe was a skilled politician—he had been a member of the Continental Congress, our U.S. senator, Secretary of State, Secretary of War, a diplomat, and Governor of Virginia— who could embrace the contradictions and sell them to skeptics. His optimism and kind personality were infectious. He completely ignored any remaining self-identifying “Federalists” and went about an ambitious agenda of national expansion, while checking the ever-looming threats of colonial European powers.

It goes without saying that The Era of Good Feelings was misery for many in America. The acquisition of Florida and settlement in western territories endangered the lives and sovereignty of Indian tribes. Slavery was the foundation of the national economy. Monroe claimed to be an abolitionist, though he owned approximately 250 enslaved people in his lifetime. To be clear, he insisted on gradual emancipation… so gradual that he only freed one person, at the end of his life. But even as conflicts over slavery grew, the Era provided a solution meant to please: the Missouri Compromise. With it, the balance of free and slave states would be preserved in Congress. The law merely staved off the larger issue, which would only fester as the nation expanded its borders. The Missouri Compromise, like Monroe’s personal views on slavery, was a way of having it both ways. At least politically, the good feelings held for those who could cast a ballot. Monroe ran virtually unopposed for reelection, in 1820. He lost only one electoral vote.

President Monroe is most remembered for the Monroe Doctrine, which he delivered in 1823. As America engaged in eternal power struggles with European superpowers and as countries in South America, Central America and the Caribbean declared their independence from those same powers, Monroe declared that any further interference from Europe in the Western Hemisphere would be considered a threat to the United States. This demand for national sovereignty was a powerful rebuke of colonialism, though it was also convenient to eliminate those serious competitors in land conquest. Yet again, good feelings are easy once you’ve wiped out the serious competition. The logic of the Monroe Doctrine did not apply to America itself, as it waged the First Seminole War and as westward expansion infringed on the lands of Indigenous nations.

The Era of Good Feelings ran on the fumes of a conflict-weary populace, eager to have it both ways. Monroe embodied that desire when claiming that one-party rule was partyless rule; when arguing that emancipation should move at a glacial pace; and in criticizing colonialism while adopting its tactics. Having it both ways does feel good because it delays the hard decision-making of good governance. The illusion could not last long and did not endure past Monroe’s second term. The 1824 “partyless” election was an electoral debacle. By the 1828 election, two new parties, the National Republican Party and the Democratic Party, had returned us to the two-party system. Over the next 30 years, the issue of slavery acquired the partisan urgency, passion, and rage that had initially defined the Federalist/Democratic-Republican rift over federal power. Some issues are too big and too important for compromise. By 1856, America was so divided that many feared Civil War.

That year, in a seemingly desperate ploy to heal the splitting nation, the Governor of New York wrote to Virginia’s Governor, Henry Wise. In the letter, he offered to exhume the body of James Monroe (he had died 27 years earlier, in New York City) and repatriate his remains to Virginia on the 100th anniversary of Monroe’s birth. This conciliatory gesture in the face of rising North/South tensions was readily accepted by Governor Wise, who secured funding for the ensuing spectacle: the Era of Good Feelings would be resurrected.

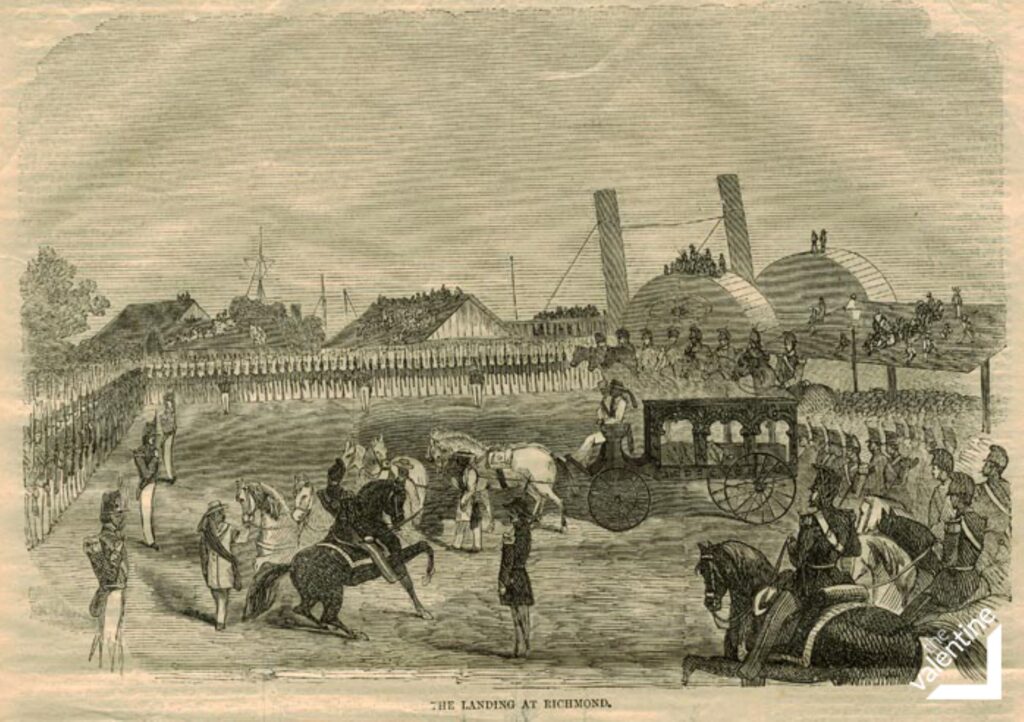

On July 2, 1858, Monroe was dug up, his coffin placed into a new coffin, and his body was escorted in a lavish parade to spend the night under guard in New York’s City Hall. The next morning, the steamer Jamestown arrived with a delegation of Virginia dignitaries. The entire party, including New York’s Governor and his 7th Regiment, accompanied the corpse down the eastern seaboard. Monroe rode in the gentlemen’s room on the upper deck, elaborately draped with black and white muslin. The steamer arrived in Richmond in the early morning hours of July 5. Governor Wise, military regiments, and a large, cheering civilian crowd were already at the wharf to greet their Northern neighbors and their beloved Virginia statesman.

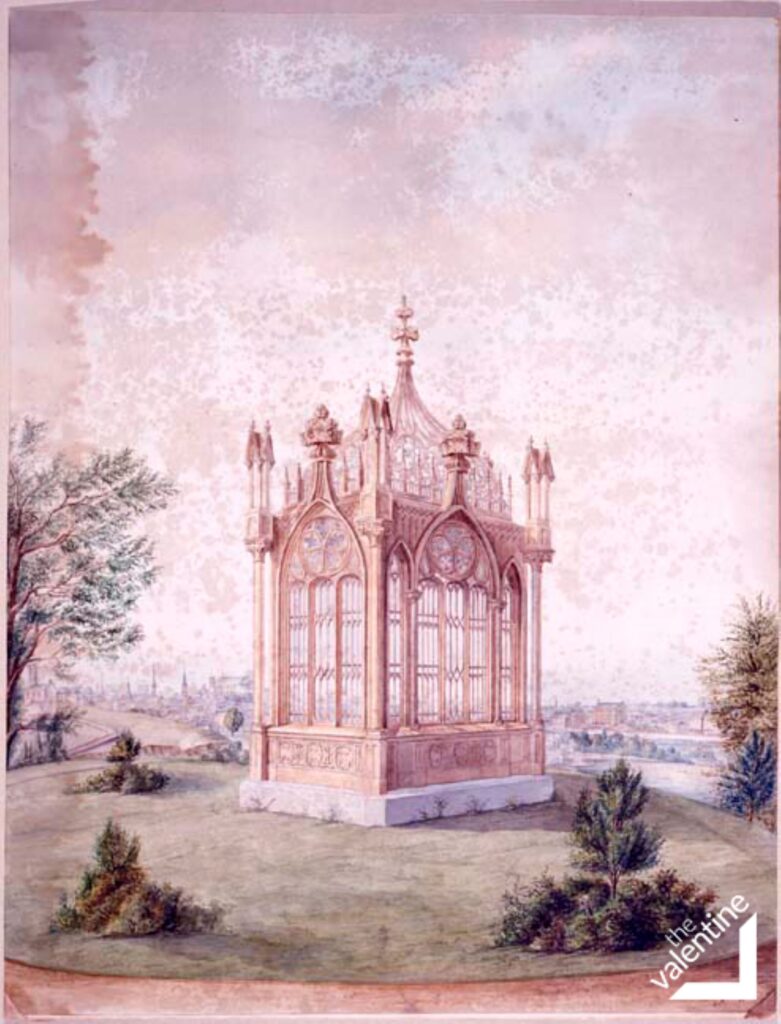

James Monroe was reinterred at Hollywood Cemetery on July 5, 1858. Richmonder Albert Lybrock won a contest to design his tomb, which the Dispatch called a “gothic temple,” and which has been recently restored to its original appearance. At the new, open grave, both governors delivered speeches on national unity. Afterwards, the delegations and military attachments from Virginia and New York celebrated aboard the Jamestown. The Era of Dug Up Good Feelings lasted well into the night. It was a great party and the entire affair was deemed a diplomatic success for both the North and the South, even if, in a spooky turn, Alexander Hamilton’s grandson fell overboard and drowned. Even if, in three years, the two sides would be at war.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | James Monroe and the “Era of Good Feelings” |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | November 14, 2021 |

| Updated | November 14, 2023 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |