Boarding Schools for Black Students Offered a Unique Education for more than 70 years

More than 12,000 African American and Native American students from across the country attended St. Emma Industrial and Agricultural Institute (est. 1895) for young men and St. Francis de Sales (est. 1899) for young women until both schools closed in the early 1970s.

By Valentine Museum Staff

In the 1890s, Edward Morrell, Louise (Drexel) Morrell and her sister, Katharine Drexel, opened St. Emma Industrial and Agricultural Institute for young men and St. Francis de Sales for young women offering an education rooted in self-reliance.

The schools were established on the former Belmead and Mount Pleasant plantations in Powhatan County. During the 1840s, wealthy plantation owner Philip St. George Cocke purchased land on the James River and built Belmead, a Gothic Revival mansion that still stands on the property today. By 1860, Cocke owned more than 27,000 acres in Virginia and Mississippi and 610 enslaved people.

More than 130 enslaved people are buried in a cemetery on the Belmead property. After his Cocke’s death by suicide in 1861, the land was sold several times prior to 1895.

In 1895, Edward and Louise Morrell purchased the Belmead plantation and opened St. Emma Industrial and Agricultural Institute on the site. In 1899, they partnered with Louise’s sister, Katharine, to purchase Mount Pleasant plantation to found St. Francis de Sales school. A small creek separated the two schools.

Louise and Katherine’s father was Francis Anthony Drexel, a Philadelphia banker, philanthropist and business partner of J.P. Morgan; his daughters inherited his fortune. Committed to her Catholic faith, Katharine established the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, an order of Catholic nuns, whose mission was to support the education of African American and Native American students in the years after the Civil War. She opened more than 60 schools and missions during her lifetime, including St. Emma and St. Francis de Sales. In 2000, the Catholic Church canonized Katharine Drexel making her the first American born saint.

Students came from all over the country by train to the Rockcastle Depot in Goochland County. They would then take a ferry across the James River and make their way up the hill to either St. Emma or St. Francis.

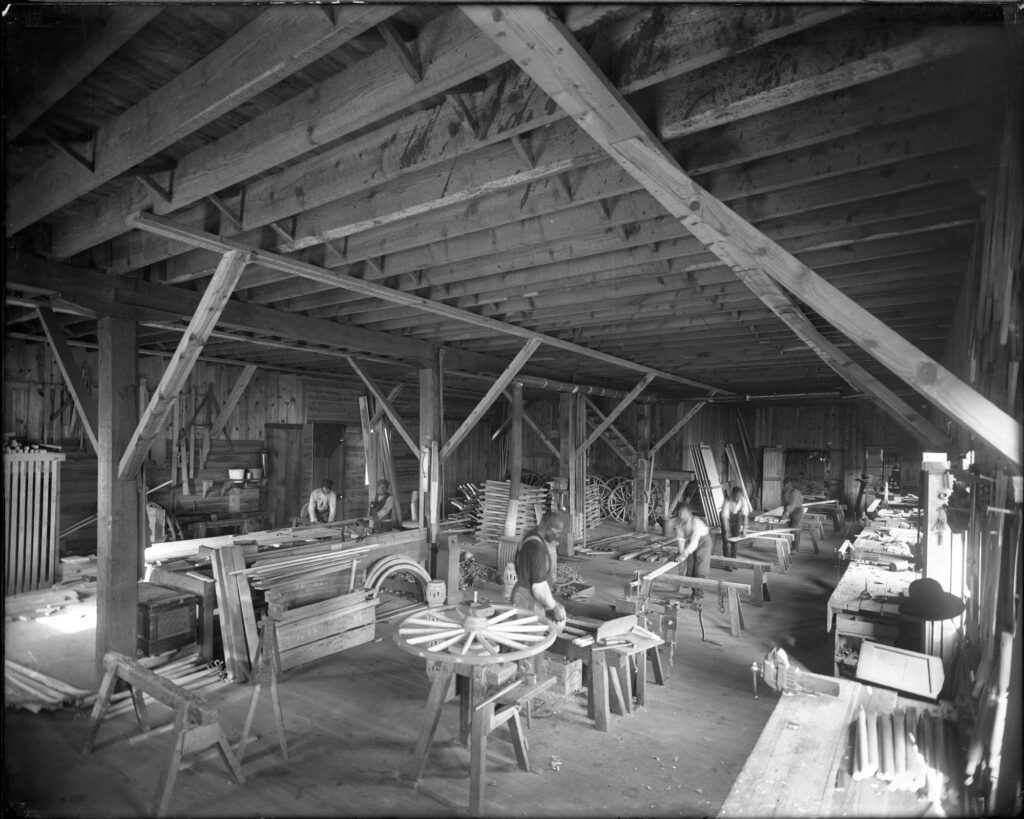

St. Emma and St. Francis offered a curriculum that focused on trades for young men and domestic skills for young women in addition to core academics. Many of the skills the students learned allowed the schools to be self-sufficient. The students grew their own food, raised their own livestock and even used their masonry skills to construct many of the schools’ buildings themselves. For a time, they operated a store where the public could buy items the students produced.

St. Emma offered 11 specialized trades including animal husbandry, carpentry, blacksmithing, mechanics, cobbling, tailoring, wagon-building and upholstery. Many St. Emma graduates received three diplomas: military, trade and academic.

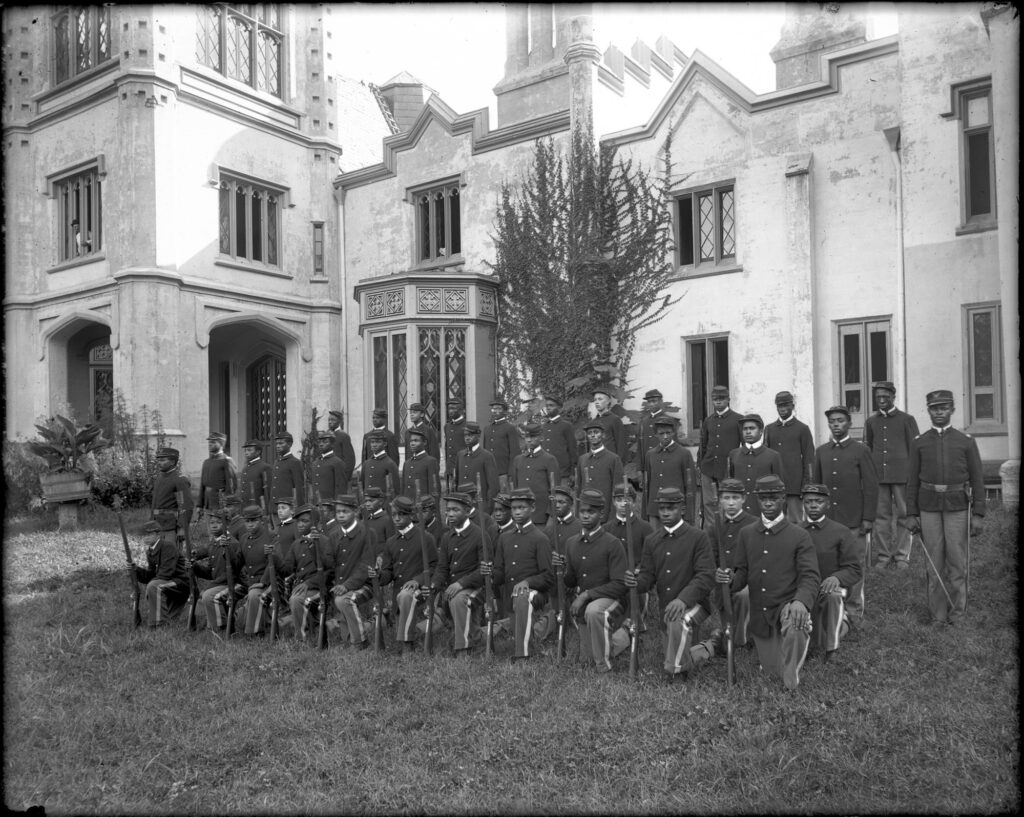

St. Emma school records indicate that in 1912, tuition, room and board cost between $14 and $17 monthly with another $2 monthly for uniforms. To be admitted, St. Emma cadets (students) had to be young men at least 15 years old, 5-foot-2 and 110 pounds and were required to follow a strict code of behavior that included no profanity, gambling, card playing or throwing dice.

In 1947, the Holy Ghost Fathers of the Catholic Church took over operation of St. Emma, changing the name to St. Emma Military School and making it the only military school for African Americans in Virginia.

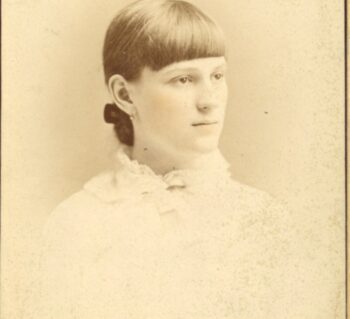

Mary Boyd, a Native American from Wyoming, was the first student to attend St. Francis de Sales in 1899. Her graduation photo was taken by Foster Studio in Richmond in 1901.

In addition to studying traditional academic subjects, the young women at St. Francis de Sales learned domestic skills such as cooking and dressmaking from the nuns. There were classes in needlework, lacemaking and embroidery, and the students were also encouraged to participate in music, the arts and athletics.

The schools maintained separate educational spaces, but the students did mingle in mixers and dances supervised by the nuns and priests. Students remembered that the nuns often carried rulers to ensure there was an appropriate distance between the men and woman as they danced.

The combination of a protected setting away from the racial tensions in their home communities and the structure and discipline provided by both schools allowed students to develop personal interests and skills and experience the importance of service to others. With integration of public schools and more choices for education following the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, enrollment numbers at both schools began to decline. By 1972, both schools had closed.

Many of the original buildings from both schools were demolished during the 1970s, but the Belmead mansion and the main building and chapel of St. Francis de Sales along with a few other buildings remain. A handful of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament stayed to take care of the property.

The Youth With a Mission, a Christian missionary organization, used the St. Francis building for several years in the early 1970s, but the building has sat empty since then. For almost 10 years beginning in 1987, Blessed Sacrament High School, a coed day school, was located in the remaining St. Emma buildings.

In 2006, the Virginia Outdoors Foundation, the James River Association and the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament worked in partnership to place 1,000 acres of the land once occupied by both schools in a conservation easement to protect against future development. The remaining sisters created FrancisEmma Inc., a nonprofit to save the land from being sold and developed.

Preservation Virginia listed St. Francis de Sales as one of Virginia’s Most Endangered Historic Sites in 2007. During this time, the price of restoring the buildings continued to increase as the structures further decayed, including the bell tower’s collapse and water damage to the chapel at St. Francis.

In 2019, after a number of preservation and fundraising efforts failed, the leadership of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament sold both school properties to a private individual.

Alumni of both schools continue to work to have their stories recognized and celebrated in Virginia’s historic legacy.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Valentine Museum Staff |

|---|---|

| Work Title | Boarding Schools for Black Students Offered a Unique Education for more than 70 years |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | May 1, 2024 |

| Updated | May 24, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |