Essay: Edward Valentine’s Studio

Edward Valentine’s artist’s studio first served as a carriage house with stable and bath for Thomas Green. Valentine acquired the structure in 1871 and converted it into his studio, where he worked for nearly 50 years.

By Kate Sunderlin

Ph.D., Co-Curator of Sculpting History: Art, Power, and the “Lost Cause” American Myth

Hayes-Green-McCance Carriage House

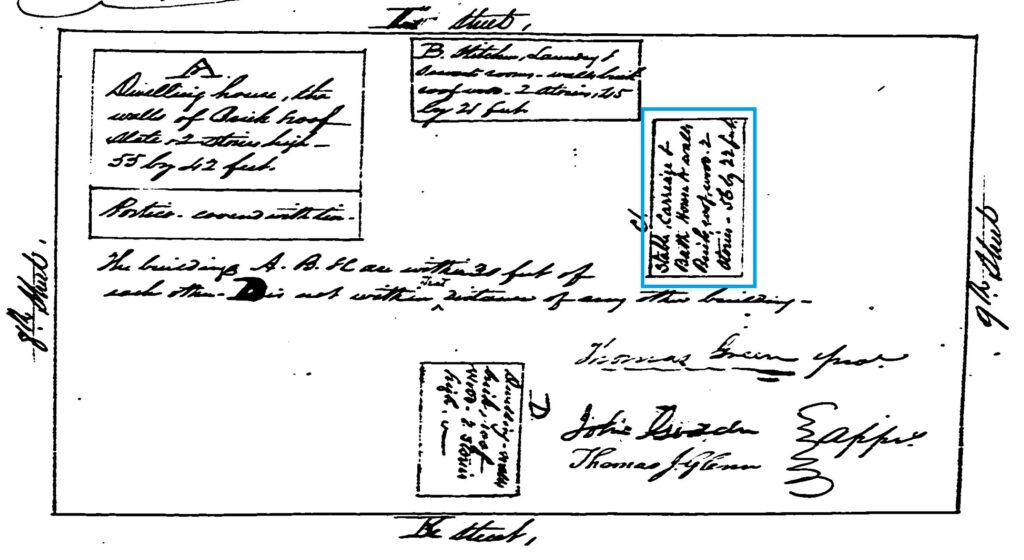

By 1836, unknown laborers had erected a two-story “stable, carriage, and bath house” with walls of brick and a wooden roof for Thomas Green. It was one of two insured outbuildings that served Green’s main dwelling located at the corner of Leigh and 8th streets. Thomas Green had acquired the main dwelling house and land back to Clay Street from John Hayes in 1832. His significant improvements to the property also included ornamental grounds as well as updates to the nearly twenty-year-old home. But by 1842, Green, a land speculator, had run out of money and mortgaged the property. Thomas W. McCance bought the home and outbuildings that year for $15,000. The McCances lived there for over 40 years but parceled off the carriage house in August of 1871 to Edward Valentine. In an interesting twist, Valentine’s brother, Mann S. Valentine II (1824-1892) purchased the older Hayes-McCance house next door in 1888. It was demolished in 1893.

The Studio

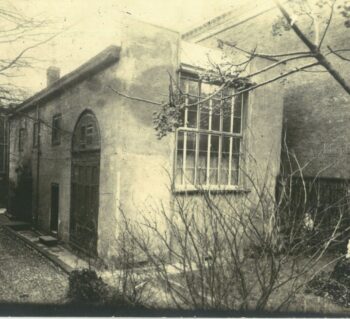

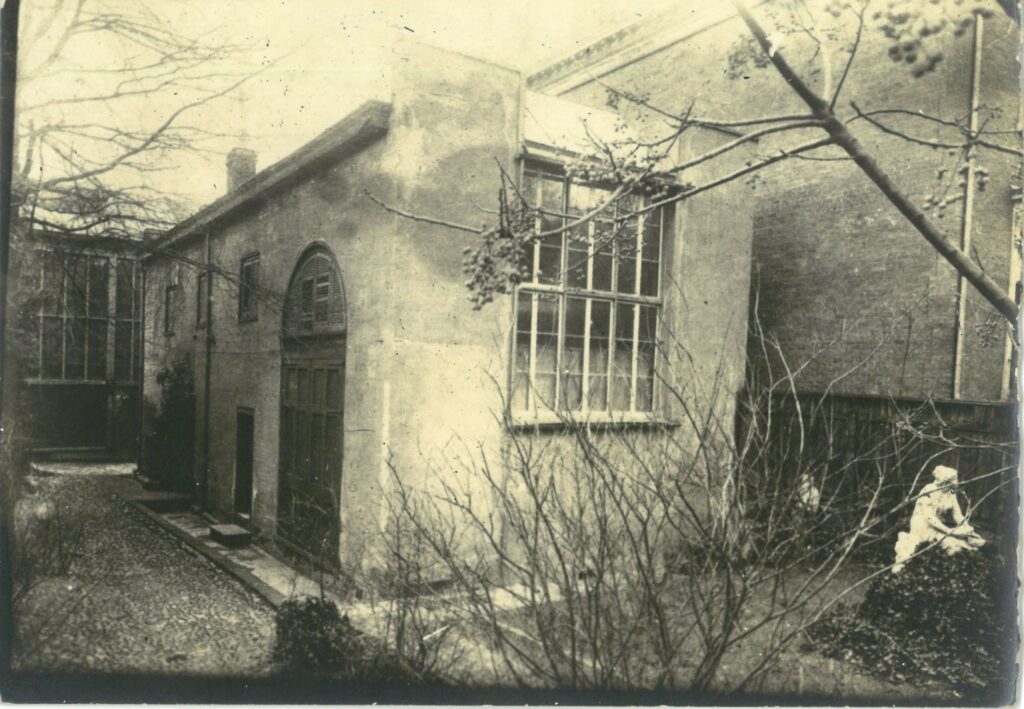

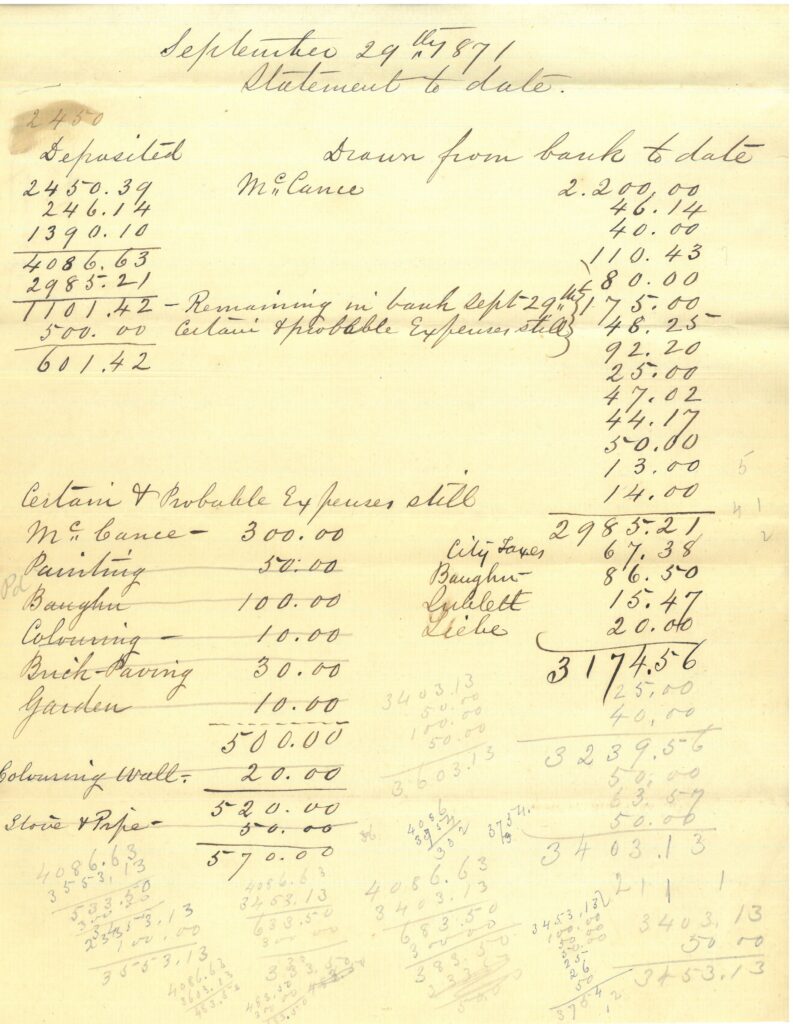

Edward Valentine was an active sculptor in Richmond after he returned from Europe in the summer of 1865. He operated out of his mother’s home at 6th and Capitol streets as well as his brother’s dry goods store on Main Street. In August 1871, soon after receiving the commission of a monument for Robert E. Lee’s tomb, Edward Valentine purchased the skinny lot and structure at 809 ½ Leigh Street from Thomas McCance for $2,500. It measured 22 by 56 feet, and he immediately set to work renovating the space. In addition to painting, shelving, and adding heating elements to the building, he also had a contractor install two skylights and a large bank of windows on the north wall to illuminate his work with soft light.

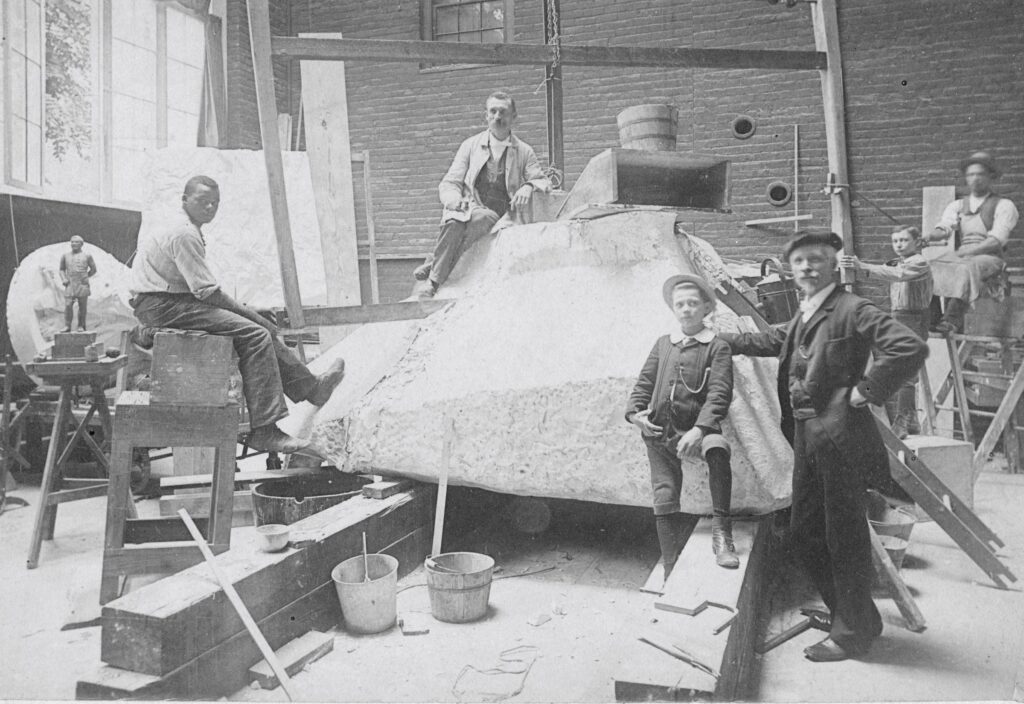

By the late 1880s, Valentine’s reputation had grown so that he had an increasing number of larger commissions necessitating an expansion to his studio. He broke ground in September 1889 for a larger building behind his Leigh Street studio known as the Annex that he used for casting and marble-cutting. According to newspaper accounts, it was to be the largest in the country.

Once the Annex was complete, Valentine used his older studio as a modeling studio where he could receive guests and clients and display smaller works. Some of his more famous guests included future U.S. President Woodrow Wilson in 1898, then president of Princeton University, British author Oscar Wilde in 1882, and Lost Cause supporter General Jubal A. Early on numerous occasions. Valentine retired from sculpting around 1910.

The Afterlife of Valentine’s Studio

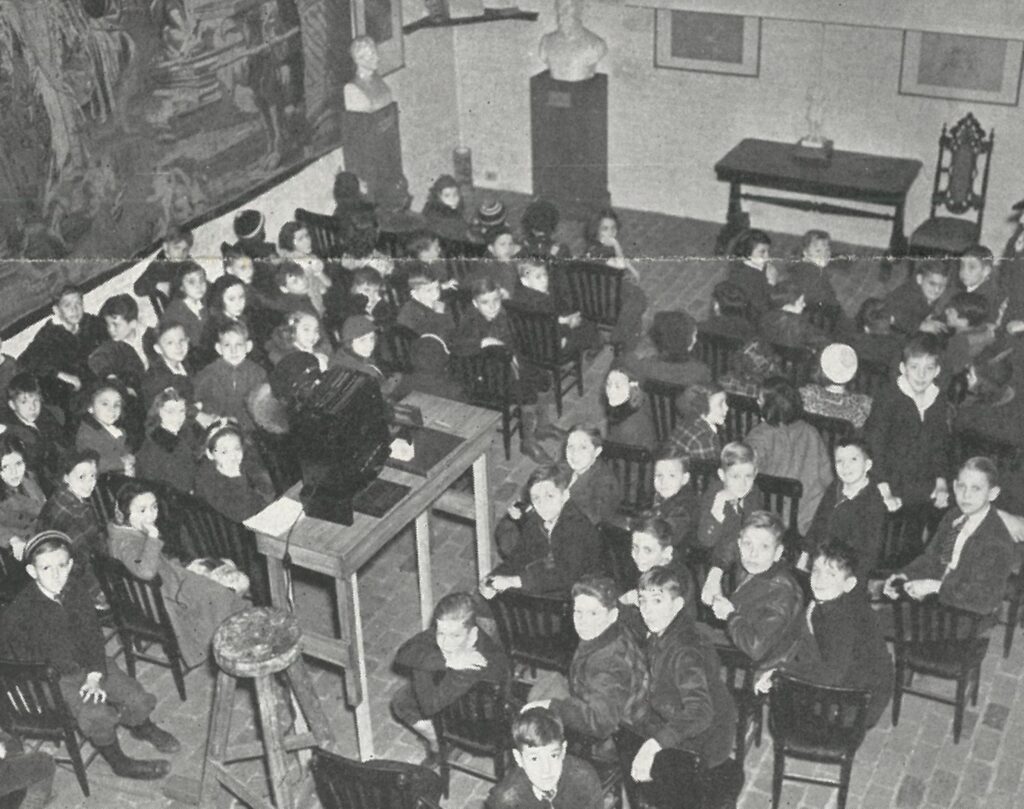

In 1926, Valentine sold his studio at 809 East Leigh Street to his great-niece, Ann Valentine Kelly of New York. Between 1928 and 1930, Kelly rented the space to Richmond artist Edmund Archer (1904-1986). While occupying the space, Archer, a white man, painted many Black men and women and additionally supported other Black artists in Richmond. Valentine died in 1930 and in 1932 Ann (now Ann V.K. Cesare) and her husband, O.E. Cesare, sold the property to Charles S. Valentine. In 1936, the city condemned the property through eminent domain to provide land for the expansion of John Marshall High School’s athletic fields. Friends of the Valentine Museum negotiated with the City Council and the School Board in order to acquire the studio with the intent of relocating it to the Museum for use as an educational space. The city funded the moving of the studio and rebuilding it in the backyard of the museum’s property at 1015 East Clay Street. Then-Director Helen G. McCormack said that if this was arranged by the City Council then the museum would maintain the building permanently.

While being used as an educational space and perhaps exhibition overflow space, the studio did contain “original models and mementoes” of Valentine’s. Inside the space were casts after Valentine’s busts and statues, a large seventeenth-century tapestry purchased by Valentine when in Europe, as well as the collection of death masks given to Valentine by his teacher August Kiss. The studio finishes were altered (skylight removed, ceiling plastered, and brickwork laid for the floor) as the museum intended to use the space for both exhibitions and programming. The museum installed two pull-down screens in the space, as well as cloth curtains for the windows to accommodate slide presentations. The museum received support for this initiative from local educational leaders and politicians, including Senator Henry T. Wickham, who wrote that he took “the deepest interest in preserving the theatre of Mr. Valentine’s life and work,” as he had lived long enough to have visited the studio when Valentine was working on his Recumbent Lee.

The studio was primarily used for storage in the 1950s until the late 1960s when it was once again renovated, having recently been “cleared enough to hold an embroidery demonstration and tea there.” A picture of the space accompanying a news article announcing the pending renovation shows a view of the studio from the loft space therein with several busts in the foreground. Also featured in the space was Valentine’s Andromache and Astyanax as well as chairs and a table, perhaps left over from the demonstration and tea.

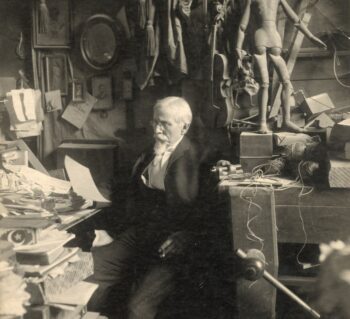

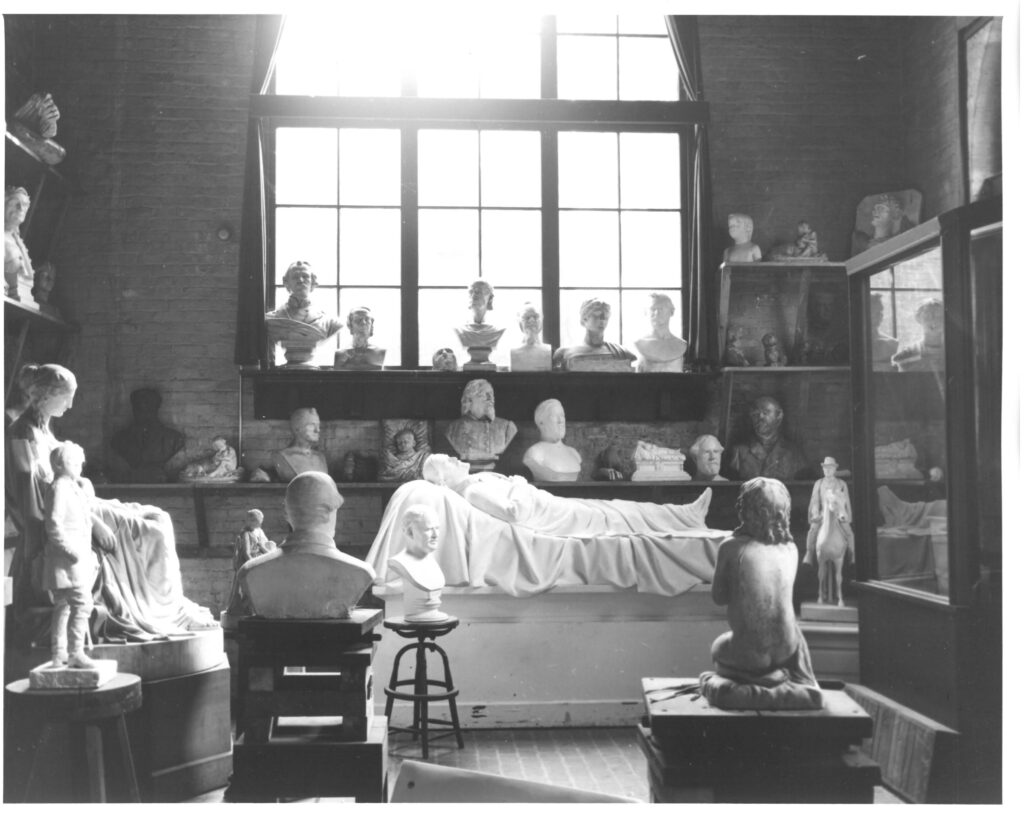

Unlike the 1930s iteration of the studio, the renovated studio opened in 1970 had more of the performative and staged nature of the studio typical of so many artists’ studio-homes. In fact, it was presented like a life-size diorama. Visitors would peer through a large viewing window cut into one side of the studio where they would get “a vivid firsthand look into the real workroom of a professional artist of an earlier era.” Researchers would be allowed to enter the space with special permission from the director. The studio aimed to recreate the cluttered feel of Valentine’s studio seen from period photos of Valentine in his studio, as well as the sense that this was still an inhabited space, to the extent that sawdust was placed on the floor. In addition, a utilitarian iron stove, rocking chairs, and stacks of books populate one corner of the room, while everywhere, “jostling for space on shelves, benches, floor, the solid evidence in marble, bronze and clay of a long and productive career.” Many works were placed on wooden shelves, added because of the shelving seen in period photographs, and Valentine’s tools, molds, sculptures, and personal effects were all staged to imitate these photos. Because of this focus, the museum also continued to showcase the heroes of the Confederacy and uncritically displayed Valentine’s racist caricatures of African Americans. The space was largely meant to be experienced visually, as visitors were only able to view the room through the large window and pieces were largely unidentified. It was not until the late 1990s and early 2000s that the objects would once again be reinterpreted to give museum goers a fuller sense of Valentine’s life and career within the context of nineteenth-century American sculpture.

By the late 1990s, the Edward Valentine Sculpture Studio had fallen into disuse when the museum planned another restoration. This restoration was intended to be a major undertaking to better preserve the space, Valentine’s works, and more fully interpret his life and works for the public, allowing them greater access as well. The goal for the early 2000s project was to curate a space that placed Edward Valentine within the sculptural canon of the United States, relating him to his more well-known peers like Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Daniel Chester French. The studio was organized according to four principal themes: “Becoming an Artist,” “Earning a Living,” “Engaging Heart and Mind,” and finally “Creating Heroes.” The exhibition aimed to “offer a critical look at the success and failure of Valentine within the larger context of American sculpture.”

But, it glossed over Valentine’s social circles and cultural environmental in which he lived and where the false narratives of the Lost Cause thrived. By uncritically displaying Valentine’s “heroes of the Confederacy” the space became a place where southern nationalism was allowed to survive. Though the racist nature of Valentine’s pieces and his ties to the Lost Cause were acknowledged in labels, the display of the pieces went unchecked, meaning the visual hierarchies created in Valentine’s studio and in the Valentine Museum during his lifetime were re-created here. For example, racist caricatures of African Americans were placed directly next to portraits of Confederate leaders and sensitive portrayals of white children. Their unfiltered presence in the space allowed them to continue to shape the public’s perception of people of color.

The Valentine Studio as curated in the early 2000s presented a space that is supposed to capture a specific moment in time yet read as timeless. It is staged as if the artist just exited stage left and because of this the studio read as sympathetic to the Lost Cause. But, the Valentine Museum is an institution committed to evolving in order to address the changing needs of its community. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the museum began to acknowledge that its collections and exhibits over-represented certain communities and stories while omitting others. It also began to actively collect and explore more diverse narratives to address this imbalance.

Major events within the last decade have brought even more change. The shocking and senseless murders of Black worshippers in 2015 at Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church by a white supremacist prompted many people and institutions to more deeply question how the Confederacy was portrayed and to remove lingering symbols of the Confederacy, like the Confederate flag and monuments. At this time, the Valentine Museum covered over its label “Creating Heroes.” New Orleans took down its Confederate monuments in 2017, followed by Charlottesville’s vote to take down the Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson statues, which led to ‘Unite the Right’ rallies in August 2017.

While the City of Richmond debated what do with its Confederate monuments, the Valentine opened a rapid response exhibition in 2018, Monumental: Richmond’s Monuments, detailing the city’s long history of monuments. The Valentine followed it with a collaborative exhibition and design contest: Monument Avenue: General Demotion/General Devotion in 2019, which invited teams of planners, architects, designers, artists and individuals to participate in a national design competition to conceptually re-imagine Monument Avenue and contribute to the ongoing dialogue about race, memory, the urban landscape and public art.

At the start of 2020, the Valentine Museum knew that the Valentine Studio needed updating. At almost 20 years old, the 2003 installation no longer met the needs of the community. The international pandemic and social justice protests after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis were the ultimate turning point. When the museum reopened to the public in June 2020, the Valentine kept the Studio closed and committed to a thorough community engagement process to determine the future of the space.

Sources

- Declaration for Policy No. 9796, Vol. 99, Mutual Assurance Society Papers, LVA, December 31, 1836.

- Mary Wingfield Scott, Houses of Old Richmond (New York: Bonanza Books, 1941),138-141

- Elizabeth Gray Valentine, Dawn to Twilight (Richmond, VA: William Byrd Press, Inc., 1929).

- Barbara Batson, Ned’s Sheds, unpublished manuscript, 2001, Valentine Museum

- Richmond City Deed Book 94B, pg. 496.

- Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, VA), September 21, 1889.

- The State (Richmond, VA), November 13, 1889.

- Edward Valentine Studio Guest Register, 1875-1909, Edward Valentine Papers, The Valentine.

- Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 18, 1928;

- “Archer,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 13, 1938, pages 5, 7;

- “Craig House will Present Bolling Works,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 9, 1939.

- Though it was Ann who received the $3000 in compensation, not Charles. “Friends of Valentine Museum Ask Council to Save Studio,” Times-Dispatch (Richmond, VA), September 10, 1936.

- “Friends of Valentine Museum Ask Council to Save Studio,” Richmond Times-Dispatch (Richmond, VA), September 10, 1936.

- “Opening of Valentine Studio Today Recalls City History,” Richmond Times-Dispatch (Richmond, VA), April 8, 1937.

- “Local Educators Back Plan to Rebuild Valentine’s Studio in Rear of Museum,” Richmond News Leader (Richmond, VA), n.d. (in the Valentine Museum)

- “Valentine Studio to Open Soon,” Times-Dispatch (Richmond, VA), July 3, 1969.

- Alison Griffin, “Sculptor’s Studio Is Secluded in Garden,” Times-Dispatch (Richmond, VA), September 10, 1976.

Need to cite this?

| Authors | Kate Sunderlin, Ph.D., Co-Curator of Sculpting History: Art, Power, and the “Lost Cause” American Myth |

|---|---|

| Work Title | Essay: Edward Valentine’s Studio |

| Website | https://thevalentine.org |

| Published | November 2, 2023 |

| Updated | May 24, 2024 |

| Copyright | © 2024 The Valentine Museum |